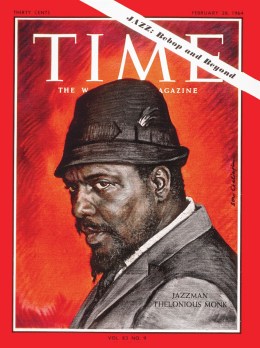

ISSUE DATE: Feb. 28, 1964

THE BUZZ:

Monk has arrived at the summit of serious recognition he deserved all along, and his name is spoken with the quiet reverence that jazz itself has come to demand. His music is discussed in composition courses at Juilliard, sophisticates find in it affinities with Webern, and French Critic Andre Hodeir hails him as the first jazzman to have “a feeling for specifically modern esthetic values.” The complexity jazz has lately acquired has always been present in Monk’s music, and there is hardly a jazz musician playing who is not in some way indebted to him. On his tours last year he bought a silk skullcap in Tokyo and a proper chapeau at Christian Dior’s in Paris; when he comes home to New York next month with his Finnish lid, he will say with inner glee, “Yeah—I got it in Helsinki.” The spectacle of Monk at large in Europe last week was cheerful evidence of his new fame—and evidence, too, of how far jazz has come from its Deep South beginnings. In Amsterdam, Monk and his men were greeted by a sellout crowd of 2,000 in the Concertgebouw, and their Düsseldorf audience was so responsive that Monk gave the Germans his highest blessing: “These cats are with it!” The Swedes were even more hip; Monk played to a Stockholm audience that applauded some of his compositions on the first few bars, as if he were Frank Sinatra singing “Night and Day,” and Swedish television broadcast the whole concert live. Such European enthusiasm for a breed of cat many Americans still consider weird, if not downright wicked, may seem something of a puzzle. But to jazzmen touring Europe, it is one more proof that the limits of the art at home are more sociological than esthetic.

Read the full story here