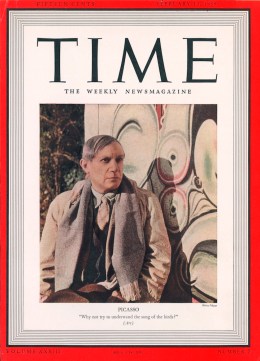

ISSUE DATE: Feb. 13, 1939

ALSO APPEARED: June 26, 1950; May 26, 1980

THE BUZZ:

In Paris last week, at the Galerie Paul Rosenberg in the fashionable Rue La Boétie, 33 small oils-on-canvas were making the art news of the season. With one exception they were still-lifes of candles and flowers, fruits and mandolins, pitchers and bird cages, ox skulls and oil lamps, knives, forks figurines and doves. Had these objects been painted with the luscious realism of a soup advertisement, the pictures would not have been at Rosenberg’s, nor would they have interested any of the people there. Yet if there was one thing these doodles, lozenges, swabs and swishes of bright paint represented to that crowd of connoisseurs and jealous artists, it was sheer technical virtuosity— probably the greatest painting virtuosity in the world.

So, for 30 years, have the works of Pablo Picasso continued to delight the knowledgeable and confound the common man. Flying like a shuttlecock between the esthetic debaters of two continents, the very name of Picasso has been a symbol of irresponsibility to the old, of audacity to the young. To millions of solid citizens it has been one of the two things they know about modern art— the other being that they don’t like it.

Read the full story here