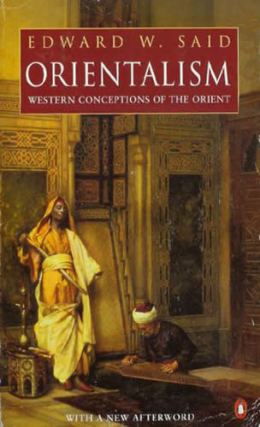

The late Edward Said, a polyglot, eclectic Palestinian-American intellectual, is the unlikely patriarch of the school of postcolonial studies, which over the past three decades has been the primary vehicle for academic study of countries in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia and elsewhere. (Said, a professor at Columbia University, was a specialist in Western literature and was obsessed with classical music.) His landmark work, Orientalism, published in 1978, took to task the entire way scholars in the West approached the non-West, focusing on Said’s home terrain in the Middle East. It’s impossible, claims Said, to disassociate the subject of Western “Orientalist” inquiry from the context of imperial power; the Orient, in the eye of the Orientalist, was not a real place but a theatrical “stage annexed by Europe” where thinly veiled stereotypes of “the Other” that grew out of a false dichotomy were created and affirmed. Many latter-day Orientalists object to this typecasting, but it’s because of Said’s deeply humanist vision that we now approach the idea of distinct “cultures” and “civilizations” with the healthy dose of skepticism it deserves.