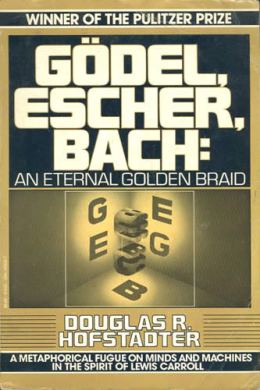

In 1980 a 34-year-old professor of computer science at Indiana University named Douglas Hofstadter won the Pulitzer Prize for Godel Escher Bach, making it one of the greatest and most unlikely success stories in the history of the prize. Hofstadter’s book utterly defies categorization: it’s a vast, playful, manically interdisciplinary argument/fantasia about three radical thinkers and the way their work relates to the nature of human consciousness. Ordinary language can’t convey Hofstadter’s ecstatically brilliant improvisations: he uses paradoxes, palindromes, dramatic dialogues, koans, diagrams, symbolic logic, musical scores and, where necessary, terrible puns to braid music theory, mathematics and the visual arts into one single strand that leads the reader deep into the mystery of how the mind works. Even if you don’t grasp the entirety of his argument, it’s enough to watch Hofstadter’s own mind work. His ability to leap from one idea to another, unhindered by disciplinary boundaries, spotting connections and analogies between wholly disparate fields of knowledge, was unlike anything anybody had ever seen before, and it inspired a rising generation of thinkers to make connections of their own.