Caesar's Hour

He was the Brando of TV comedy. Look today at his work on the four shows he anchored in the medium’s infant days: Admiral Broadway Revue (1949-50), Your Show of Shows (1950-54), Caesar’s Hour (1954-57) and Sid Caesar Invites You (1958). There, in “live” sketches with a wit, drive, sophistication and narrative shapeliness put to shame all that came after, you will see the first and greatest Method comic.

Caesar’s physicality calls to mind no other comedian; he summons images of Robert De Niro (even to the mole on his cheek), Nicolas Cage, James Gandolfini, Christian Bale. Sid dominates, he broods, he hulks. A large man, not really handsome but imposing, with huge hands and barely controllable strength, he intimidates the small screen, fills all its space, sucks out its energy.

(READ: James Poniewozik on Sid Caesar, “Your Comic of Comics”)

Caesar, who died yesterday, Feb. 13, 2014 at 91, was actorish in another way. He lacked the laugh-at-me, love-me assurance of the stand-up comic; Sid, introducing Your Show of Shows each Saturday night, had exactly the poise and flair of his Sunday-evening counterpart, Ed Sullivan. “Without a character to hide behind, Sid was lost,” Caesar writer Larry Gelbart recalled in his autobiography Laughing Matters. “Sid simply did not know how to play Sid.” At a 1996 Writers Guild reunion of the Caesar staff, Sid tried to describe working with his Show of Shows co-star Imogene Coca: “As soon as we met, there was a certain, ah — uh — camaraderie. A certain — I — ya can’t —there’s no name for it.” Next to him, Mel Tolkin, Caesar’s longtime head writer, murmurs helpfully, “Try ‘spark.’ That’s as good as anything.” He fits the image of the big-lug serious actor, inarticulate but sensitive.

And given to fits of rage — as Gelbart says, “Sid and rages were a perfect fit” — especially in the writers’ room, where the weekly script was prepared. Neil Simon recreated that tension in his 1993 Broadway comedy Laughter on the 23rd Floor, starring Nathan Lane as TV comedian Max Prince. Here’s Simon’s description of Max: “He dominates a room with his personality. You must watch him because he’s like a truck you can’t get out of the way of.”

(READ: William A. Henry III’s review of Laughter on the 23rd Floor)

In the play, Max puts his fist through a writers’ room wall, then has the hole framed in Tiffany’s silver. In real life, according to Gelbart, “Sid yanked an offending washbasin out of a wall with his bare hands.” In 2001, Caesar was asked by a Toronto Sun reporter if it was true that in a fury he’d seized little Mel Brooks and hung him from an 11th floor window. He replied, “Nooo. It was the 18th floor.” And was Mel funnier when Caesar hauled him back in? “Nah, but he was grateful.”

You wouldn’t know it from the reminiscences, but Your Show of Shows was not, strictly speaking, a comedy show. It was an old-fashioned vaudeville bill, new each week — what Variety called “vaudeo” — and perhaps half of the 90-minute show was consumed by musical acts. Bill Hayes and Judy Johnson crooned pop tunes; Marguerite Piazza sang opera; the Billy Williams Quartette offered suave rhythm stylings; the Hamilton Trio or the duo of Bambi Lynn and Rod Alexander performed a dance number. Those parts of the show were the property of Max Liebman, its producer and a Ziegfeld of the 12-inch screen, who put the whole thing on for a miserly $64,000 a week. (When Sid mentioned this at the Writers Guild reunion, Caesar writer Sheldon Keller snapped, “I saw the same show at Kmart for $28,000.”) You also wouldn’t know, from studying The Sid Caesar Collection, furtively available on video, who actually directed these shows. For the record, the names are Greg Garrison and Bill Hobin for Your Show of Shows, Clark Jones for Caesar’s Hour.

Sid Caesar in Your Show of Shows.

You might also not know, unless you were (like me) a comedy-crazy kid at the time, the gifts of Caesar’s supporting cast. Carl Reiner, who was also a writer, and earned TV immortality for creating The Dick Van Dyke Show, was the main foil, invaluable for keeping a straight face through Caesar’s preemptive ad-libbing. In skits he had the height and stern visage to play the villain. He also had a hilarious and acute tenor wail, too rarely displayed.

(READ: TIME’s review of Ten from our Show of Shows)

Howard Morris (later a director of many sitcoms, including Van Dyke), had an endearing elfin verve; of all the Caesar players, he knew best how delicately a gesture could be pitched to the camera — though as Uncle Goofy in the famous “This Is Your Story” sketch he went gloriously bonkers, clinging to Caesar’s leg and, in one inspired moment, jackknifing from his backward sprawl over a couch arm up into Sid’s clutches. He and Reiner were both adept in foreign-language double-talk; they could keep up with Caesar in the Italian, German, French and Japanese parodies that provided the shows with their most dizzying comedy.

Of Sid’s leading ladies, Imogene Coca (1949-54) played her tiny stature cunningly against Sid’s bulk; she was a superb pantomimist whose deft mugging surely served as the model for Carol Burnett. On Show of Shows she got nearly as much solo time, in musical and comedy bits, as Caesar; none appear on the Sid-vid cassettes. Her successor, Nanette Fabray (1954-56), had the perky looks, easy glamour and a trained soubrette soprano that helped enlarge the scope of the parodies the writers could attempt — as on the “Shadow Waltz” sketch, where she sings Harry Warren’s lilting waltz while Sid loses his fake mustache and swats a fly that has landed on her face.

Most people, though, think of early sketch TV as a writer’s medium. Indeed, the Caesar shows may be remembered less for their terrific sketches than for the later careers of the people who wrote them. Gelbart: A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum on Broadway, Oh, God! and Tootsie in the movies, M*A*S*H on TV. Tolkin: All in the Family (he wrote 36 episodes). Aaron Ruben directed The Phil Silvers Show, aka Sgt. Bilko, and produced The Andy Griffith Show and Sanford and Son. Gary Belkin wrote scripts for Newhart and Sesame Street. Lucille Kallen wrote the C.B. Greenfield mystery novels. Selma Diamond became a familiarly rasping voice on Jack Paar’s late show and lots of cartoons. Joe Stein and Mike Stewart went to Broadway; one wrote the book for Fiddler on the Roof, the other the libretti for Bye Bye, Birdie, Hello, Dolly and Barnum. Brooks and Simon and Reiner you’ve heard of; and Woody Allen, who came in toward the end of Caesar’s nine-year reign.

(READ: Jame Poniewozik’s remembrance of Larry Gelbart)

The very phrase “Caesar’s writers’ room” conjures up a maelstrom of comedy competition. Looking back, the survivors sound proud and grateful. They say writing for Caesar was like playing for the Yankees, or in Duke Ellington’s band. Neil Simon called it “the Harvard of comedy.” But the reality was closer to a grudge handball match. Says Gelbart: “It was very much like going to work every day of the week inside a Marx Brothers movie.” Some writers were businesslike (Tolkin), some quick and professional (Gelbart), some were quiet (Neil Simon would mumble a fine gag sotto voce, and Carl Reiner, sitting next to him, would pitch it). And one was nuts. If Caesar focused the writers’ fear and awe, Brooks channeled their fury. “He was always late,” says Gelbart. “He’d come in with a Wall Street Journal and a bagel. He wanted to be a rich Jew.” Brooks recalls it differently: “I should’ve been impressed but I wasn’t, because I was a cocky kid, and I was filled with hubris and this marvelous ego. I thought I was God’s gift to creative writing — and it turned out I was.”

Here is the voice of the tummeler, the wise-ass Jewish kid. For many watchers of early TV, the Caesar spectacle provided their first taste of sophisticated Jewish wit. (Milton Berle, Eddie Cantor and Jerry Lester walked a lower road; Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis swerved manically, dementedly off it.) The writers’ room didn’t contain that many college graduates, but the comedy aspired to be simultaneously high and low, elite and vulgar, educated and vigorous. Their skits in German double-talk typically use Yiddish for the punch lines. Indeed, almost anything could sound Yiddish. Consider this skit, set in an Indian restaurant, with Sid as a customer and Carl the waiter:

Sid: “What have you got to eat?” Carl: “Klochmoloppi. We also have lich lop, slop lom, shtocklock, riskkosh and flocklish.” Sid: “Yuch!” Carl: “We have yuch too. Boiled or broiled?”

“We were just a bunch of very gifted, neurotic young Jews punching our brains out,” Gelbart says. And Caesar, who supervised this menagerie and had final say over their offerings, rewarded the writers by letting both their manic wit and their ingenuity run amok. “Everything, every subject, was fair game,” Gelbart writes. “Nothing was too hip for the room. He had total control, but we had total freedom. We were satirizing Japanese movies before anyone ever saw them, fashioning material for him that sprang from our collective backgrounds, our tastes in literature, in film, in theater, music, ballet, our marriages, our psychoanalyses.”

In the ’50s shrinks were blooming all over New York; and smart showbiz types who were paid good money to make jokes about their mothers-in-law then paid some Sigmund even better money to listen to them talk about themselves. “Nearly everyone on our staff at Your Show of Shows was in analysis,” says Caesar in Where Have I Been, the story of his 25-year dependency on pills (e.g., chloral hydrate) and booze. As Simon writes of Max/Sid in Laughter, he “gets into his limo every night after the show, takes two tranquilizers the size of hand grenades and washes it down with a ladle full of scotch.”

(READ: When TV comedy changed from sophisticated to mainstream)

The addiction is understandable; he was in front of the camera, selling their skits and himself in 60- and 90-min. shows that went out live each week. To quote again from Laughter, “We WRITE comedy. Max [Sid] DOES comedy. It’s his ass out there in front of the cameras every week.” Caesar was the boy who has the nerve to stand up in class and say rude things the smarter kids have whispered to him. He also had the gumption to do comedy about his weaknesses. In “A Drink There Was” he enacts the ravages of demon rye; in “The Sleep Sketch” he gets hooked on a stimulant he thinks is a tranquilizer and spazzes into a manic jazz dance to the tune of “Piccolo Pete.”

So there is something of the tragic hero in Caesar the great. As Ira, the Mel Brooks character in Laughter on the 23rd Floor, says of his boss: “He was Moses, for crise sakes. The man is a giant. He’s Goliath. Maybe he’s Goliath after David hit him in the head with a rock, but there’s fucking greatness in him, I swear.” Watching these sketches today, I swear Ira’s not exaggerating.

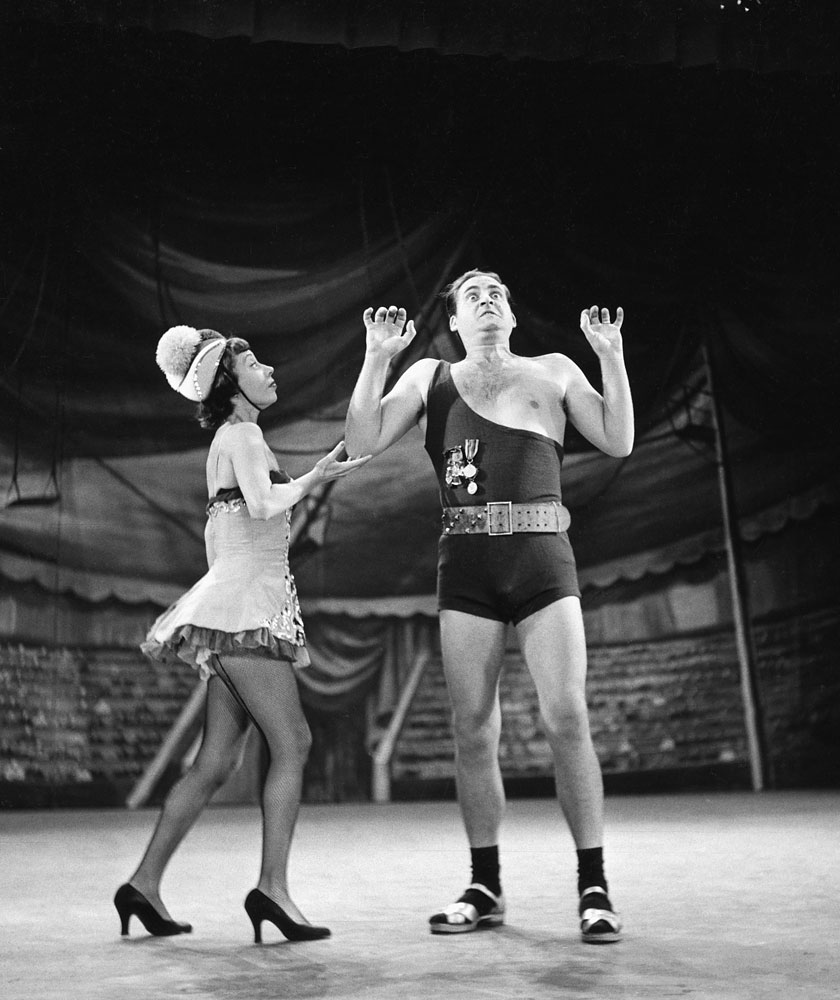

Imogene Coca and Sid Caesar in Your Show of Shows

It had to end. No one, not even the mighty Caesar, could perform this mammoth battle, an exhausting mixture of love and war, every week. By 1958, not even he could carry a comedy show angled to the smarty-pants portion of the audience, which declined in proportion as more people bought TV sets. In the beginning, as Gelbart notes, “The audiences were smarter. It was an earlier time in television: sets were more expensive, only the most affluent people bought them, and most of them were better educated. The audience has been dumbed down to a great degree, and so has the comedy — so they’ll get it.”

The Dream Team of Comedy broke up, the writers occasionally hiring their old boss. Simon wrote the Broadway show Little Me for Caesar — eight roles, as the men in the life of a showbiz sexpot — and cast him in The Cheap Detective. Brooks gave Caesar roles in Silent Movie and History of the World, Part I. In another movie, Brooks memorialized an incident from the Caesar legend: as Gelbart tells it, Sid “once punched a horse in the face, knocking it to the ground because the animal had had the audacity to throw his wife off its back.” Brooks gave the bit to Alex Karras as the lumbering Mungo for one of the most memorably audacious moments in Blazing Saddles.

(READ: TIME’s 1962 review of Little Me)

Caesar never regained his huge stride. He had startled, with movie-actor threat and menace, in a medium that came to prize miniature likability, that relied on little stars whom the audience could welcome, like a docile dinner guest, each week into their living rooms. He starred in “Little Me” on Broadway, but on TV, at 36, he was finished. He never again fronted his own series on American TV; his film appearances were guest shots except for starring roles in two lame William Castle mystery-comedies of the mid-60s, The Spirit Is Willing and The Busy Body.

Old fans would see him in the corners of Grease (in which he replaced porn star Harry Reems!) and Airport 1975 and wonder what happened to Sid. Kids would ask, Who is that man? Or, rather, they wouldn’t ask. They didn’t notice. The man who was too big for TV had become invisible in movies. Caesar thus became the first in a long line of skitcom geniuses (Dan Aykroyd, Martin Short, Dana Carvey, Phil Hartman) whose short-form talents were wasted in indifferent films.

In 2001 Caesar returned, marketing his glorious past in The Sid Caesar Collection (frustratingly not available today). Conquering his addictions must have taken a lot out of him, for in the interview segments of his video compilations he looked frail and gaunt: great Caesar’s ghost. Only his voice reminds us of the frantic majesty he brought to TV six decades ago. Any child today, digging through YouTube like a pop-culture archaeologist, will discover Caesar’s greatest sketches and feel the exultation of Schliemann when he unearthed ancient Troy. And in the video rubble, a thriving civilization, built on smart comedy and ruled by a Method emperor. Hail, Caesar!