The summer I read Colette (yes, that’s a Rosanne Cash song too) I was 17 and staying in a convent. I was a guest, I should add, brought up an agnostic by agnostic parents, and had no desire to shut myself away and enter an enclosed life of prayer and contemplation. (Nowadays the idea is more attractive. Plus they were Franciscans — vegetarians who kept dogs. Almost the ideal life.)

This sojourn came about as a direct consequence of my father’s fitting a hearing aid for their ancient mother superior, thus becoming the first person to see her without her wimple in some 60 years. This strange intimacy resulted in my father’s sending them odd gifts (kippers, oranges), which made them immensely fond of him. (They took enormous pleasure in the simplest things.) They, in turn, offered me refuge in the convent guesthouse to help me study for my Oxbridge entrance exam (which I failed miserably).

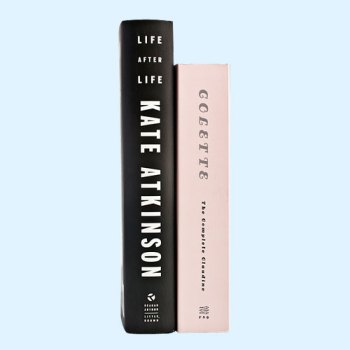

They proceeded to fatten me up as if they were planning to eat me but left me in peace in their beautiful garden to wrestle with Spenser and Chaucer. Unfortunately (or fortunately) all I remember reading are the adventures of Claudine. Claudine at school; Claudine in Paris; Claudine married; Claudine and Annie. Colette’s heroine — exuberant, willful, precocious, sexy, wise and innocent and as feline as her admirable cat Fanchette — might seem to be at complete odds with those nuns, and yet what has stayed with me after all these years is the thing they had in common — an immense, unbounded joie de vivre. I have never read those novels again; they belong, like the nuns, in the sunny, unreachable past.

Atkinson’s latest novel is Life After Life