A few weeks ago, the first black President of the United States saw a movie about the first black President of South Africa. Aside from that White House screening for Barack Obama, only four theaters are currently showing Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, which goes into wider release on Christmas Day. So viewers curious to see how the movies have portrayed Nelson Mandela — the lawyer, outlaw and convict who compelled the Boer government to give equal rights to its black majority — must forage through Netflix or Amazon.com for older films.

Perhaps no other historical figure could have seen his screen self played so favorably, and by such distinguished actors: Sidney Poitier, Morgan Freeman, Danny Glover, Terrence Howard, Idris Elba, Dennis Haysbert and, in a supporting role in the 2009 Endgame, Clarke Peters. In that TV movie, the main role, a member of the African National Congress negotiating Mandela’s release, is taken by Chiwetel Ejiofor, the star of 12 Years a Slave.

The burden of Mandela movies is that almost all of them could be called 95 Years a Saint. They are modern versions of Old Hollywood’s Biblical epics that tiptoe reverently around the teachings and personality of Jesus. And unlike Martin Scorsese’s 1988 film in which the Savior questions his divinity, there has been no Last Temptation of Nelson. Not that we’re demanding a Mandela exposé movie, but nobody has yet solved the trick of making this remarkable figure as complex as a great movie character should be. So far, most of his biopics have lacked in behavioral complexity and cinematic vitality. They are more suitable for school auditoriums than movie theaters.

The actors playing Mandela run the same risk: being hobbled by respect bordering on adoration. Because he is seen as a font of preternatural heroism and dignity, the movie Mandelas can come across as remote, flawless and superhuman, but too ethereal to be fully human. It is to the credit of the actors that, challenged to crawl into the skin of a living deity, they smolder so eloquently behind the stolid façade.

The movies could also be charged with a sort of colonialism, as Mandela has yet to be played, in any movie, by a South African. The stars of the Mandela movies are all American or British actors. And except for Faith Ndukwana in Goodbye Bafana, every actress playing Winnie Mandela has been U.S.- or Britain-born. They range from fine to great, but so would, we’re guessing, many South African performers whom a resourceful director could discover. The casting smacks of the stage and screen tradition of hiring Caucasian actors for Asian, African or mixed-race roles.

A majority of Mandela movies were also directed and written by whites — who have been in charge of virtually all South African movies that have reached North America, from Jamie Uys’s 1980 The Gods Must Be Crazy to Gavin Hood’s 2005 Tsotsi to the current Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. So many films addressing the South African scourge of apartheid approach it from the white man’s point of view. You would think that the great crime of the South African state was that whites were inconvenienced, occasionally brutalized, while the suppression and killing of millions of blacks could be taken as mere background noise.

So often in these films, the whites are the subject — the ones who inquire into apartheid and are enlightened — and the blacks the oppressed object. Made by well-meaning white liberals, the movies hew to the belief that the mainstream audience, by which Hollywood usually means people of no color, needs a white character “like themselves” to “identify with”; in this case, to lead them into the world of apartheid hurt. That’s the tactic of three apartheid dramas from the 1980s: Cry Freedom, A World Apart and A Dry White Season. Like Jesus, Caucasians heroically assume the sorry condition that afflicted all black South Africans. Moviegoers are supposed to think, Gee, isn’t life awful for them? And aren’t we wonderful for noticing it?

The reservations we express here are not intended to deride the films or the actors appearing in them. Some of the movies that follow rise to social fury and historical grandeur, with performers deeply committed to the men and women they portray. We just wish there could be, some time, a movie as inspiring and accomplished as Nelson Mandela was.

Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, 2013

Two white Englishmen — director Justin Chadwick, best known for BBC’s Bleak House miniseries, and screenwriter William Nicholson (Gladiator, Elizabeth: The Golden Age and a botched 1991 movie version of the South African musical Sarafina!) — bring Mandela’s autobiography to the screen. The film rushes through its protagonist’s adult life, offering a CliffsNotes précis of a unique life.

Mandela means to be in the mold of Gandhi, Richard Attenborough’s 1982 biopic that beat out E.T. for the Best Picture Oscar and earned Ben Kingsley an Academy Award for Best Actor. The Attenborough movie was on the starchy side, but at least its central character did things. Mandela endures his ordeal on a stately, saintly march to his own and his country’s liberation. In the early scenes of Nicholson’s screenplay, Nelson the lawyer gets to argue cases for black clients — and wins, because the whites bringing the charges are too insulted by the presence of an inferior to be subject to his cross-examination. But once in prison, he must be the voice of moderation, in effect negotiating between his more agitated colleagues and a stubborn government.

Elba, a one-man power storm as Stringer Bell in HBO’s The Wire, has also played gruff commanders — bulls with balls — in the sci-fi epics Prometheus and Pacific Rim. Here he must tamp down his energy to fit Mandela’s slimmer, quieter contours. That cedes center screen to Naomie Harris’ Winnie Mandela, the dimpled firebrand who preaches revolt in the streets while Nelson counsels talking with the politicians. Elba may be at the heart of the movie’s narrative, but Harris is its coursing, bubbling blood.

Invictus, 2009

“He can win an election,” an opposition newspaper groused, “but can he run a country?” In 1994 Mandela became South Africa’s president, ending decades of apartheid in a lightning flash of popular will. Now all he had to do was reduce crime, create jobs … and help the nation’s hapless rugby team, the Springboks, win a world championship.

Invictus, which takes its title from the William Ernest Henley poem (“My head is bloody but unbowed”) that gave Mandela strength in jail, has all the vectors of the sports-inspirational genre. There’s the impossibility of the odds, the father figure (Morgan Freeman as Mandela) whose quiet fervor wins over the players and the fans, the star athlete (Damon as Francois Pienaar) who spurs his teammates to victory with a rousing speech: “Listen to your country … This is our destiny.” What gives heft to the clichés in Anthony Peckham’s screenplay, based on the John Carlin book, are the identity of the “coach” and the high stakes involved. Mandela believes that if all his citizens can becomes adherents of this national team — long a symbol of apartheid — then the country might truly be united.

The two Hollywood stars cast as renowned South Africans work hard to find strength and nuance in their roles. Damon, beefed up for the occasion, makes Pienaar a stalwart yet courtly figure. Freeman infuses Mandela’s speeches with the same gentleness and gravity he brought to his numerous God roles and the Visa Olympics commercials. But the real deity here is Clint Eastwood, then 79, who directed this honoring, honorable scrum of a dual biopic.

(Available for rental on Netflix.)

Mandela and de Klerk, 1997

Four years after TIME chose Nelson Mandela and South African President F.W. de Klerk as its Persons of the Year, HBO showcased Sidney Poitier and Michael Caine in this star-crossed two-hander. White American action-film specialist Joseph Sargent (The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and Jaws: The Revenge, a 3-D sequel starring Caine) directed from a script by Richard Wesley, the black American playwright who in the early ’70s wrote Poitier’s ghetto comedies Uptown Saturday Night and Let’s Do It Again.

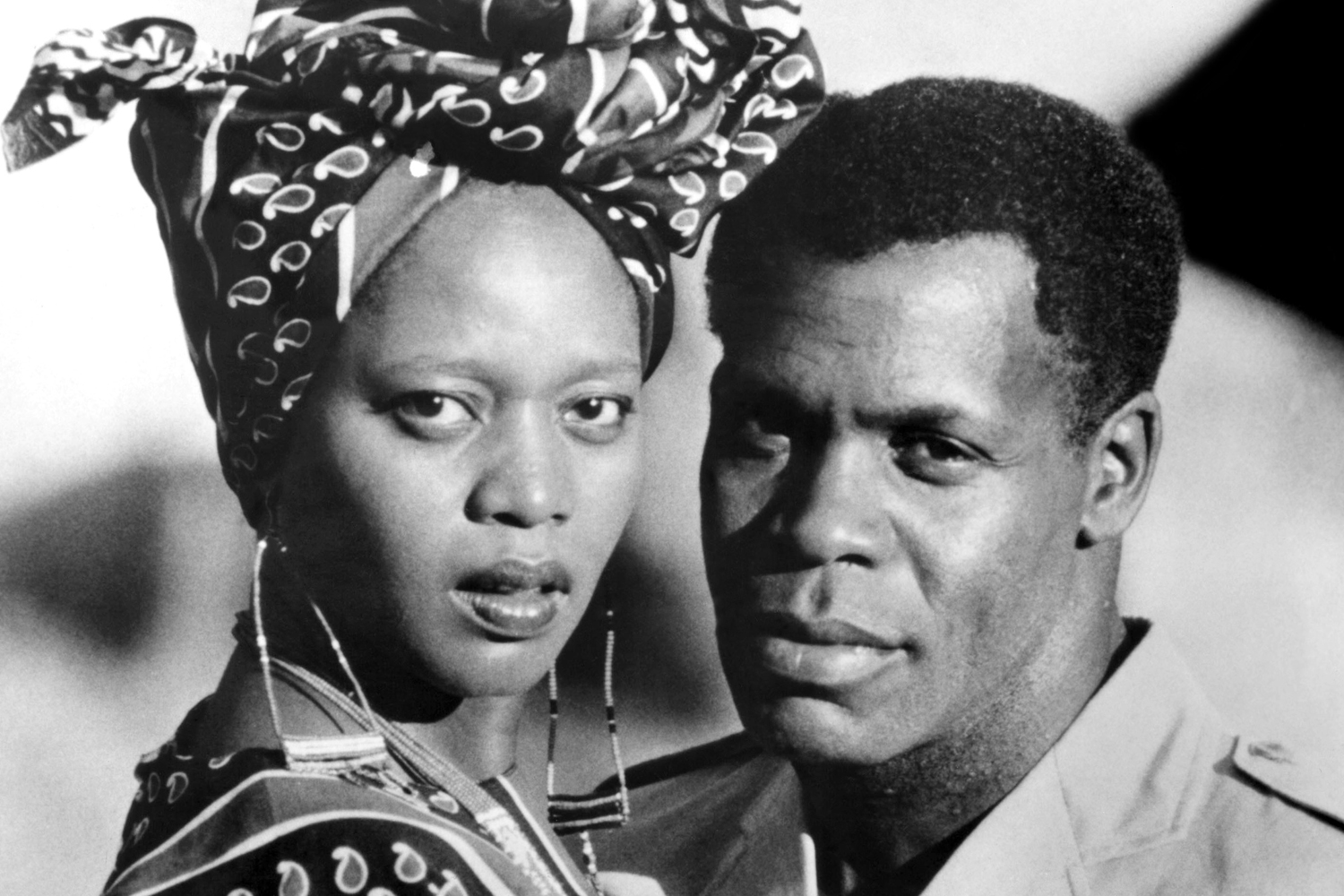

The two stars had played together in another apartheid movie, the 1975 The Wilby Conspiracy, with the Poitier character sprung from jail after 10 years for political activity, but still hounded by the police, and Caine as the engineer who helps this Johannesburg Jean Valjean elude his Afrikaner Javert (Nicol Williamson). And in 1951 the young Poitier costarred in a British-backed film version of Alan Paton’s novel Cry, the Beloved Country — perhaps the first race drama shot in South Africa in the apartheid era.

The 1997 film, while briskly synopsizing three decades of Mandela’s life, focuses on the negotiations of de Klerk and Mandela to give blacks the vote, end apartheid and transform the racist nation into a rainbow democracy. Persuasion, not violent revolution, had become Mandela’s goal; and in de Klerk he found one South African politician whose mind didn’t need to be changed. A series of conversations more intimate and less adversarial than a TV host’s with a deposed president in Frost/Nixon, the movie rests and soars on the shoulders of two supreme movie stars who rarely needed raise their voices to get their characters across with easy authority. They bring history alive in whispers.

(Available for rental on Netflix.)

Winnie Mandela, 2011

In a way, Winnie Mandela is a stronger movie subject than her husband. Nelson stoically survived 27 years in prison, nourished only by his ideals. Winnie, for most of that time, was on the outside, speaking for him to the masses, then finding her own, increasingly angry voice, becoming the revolutionary Mother of the Nation. She also suffered eight years in prison, often in solitary, forbidden even to speak aloud. While he was condemned to static sanctity, she got to do what movie characters are supposed to do: grow, learn, change, confront, overcome.

In the film directed and cowritten by Darrel Roodt, the white South African who also helmed the 1991 Sarafina! and the 1995 remake of Cry, the Beloved Country, American actors are again the stars: Jennifer Hudson (an Oscar winner for Dreamgirls) as Winnie and Terrence Howard (Oscar nominee for Hustle & Flow) as Nelson. The script’s clichés are nearly as confining to the performers as South African jails were to the Mandelas; but Hudson, slimmed down and in close-cropped hair, finds an urgent sisterhood with Winnie. In the prison scenes she reaches heroism by fighting to keep her will and wits under a system whose purpose is to drive her insane. Instead, the incarceration frees her spirit. “The harder they try to silence me,” Winnie says, “the louder I become.”

(Available for rental on Netflix; “short wait.”)

Goodbye Bafana, 2007

Dennis Haysbert played the future President of South Africa after wrapping up four seasons of 24 as the fictional President of the United States. In Goodbye Bafana, also known as The Color of Freedom, Haysbert is straitjacketed in a beatific supporting role to Joseph Fiennes (Shakespeare in Love) as James Gregory, Mandela’s letter-censorer and prison guard. Denmark’s Bille August, whose Pelle the Conqueror won an Oscar for Best Foreign-Language Feature in 1989, directed the movie adaptation of Gregory’s brush-with-greatness memoir.

Dismissed by critic Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian as “painfully worthy TV-movie stuff,” this is the all-too-familiar, Hollywoodized parable of the myopic white man who comes to see the goodness in black folks. The only blips away from blahness are the prison interchanges between Nelson and Winnie, played by Faith Ndukwana. (Stop the presses: an actual black African playing a black African!) The quiet intensity of a married couple not allowed to touch each other for 27 years is matched by their sotto voce conversations about stoking the revolution. “Escalate the armed struggle,” Nelson says in the Xhosa language that his captor cannot understand. “The country must become ungovernable.”

(Available for rental on Netflix.)

Mandela, 1987

Hollywood’s first Mandela biopic, made while he was still serving in Pollsmoor Prison, was a TV movie. Danny Glover (the year of his first Lethal Weapon movie) played Nelson, and Alfre Woodard (seen this year in 12 Years a Slave) was Winnie, in a script written by the South Africa-born Ronald Harwood (Quartet) and directed by BBC veteran Philip Saville. Filmed in Zimbabwe with armed soldiers guarding the set, Mandela came under attack from the U.S. right wing. “Even before he saw it,” wrote TIME’s Denise Worrell, “the Rev. Jerry Falwell referred to it as ‘Communist propaganda’ and threatened a Moral Majority boycott of HBO during September. Claiming that Mandela is ‘pro-terrorist,’ Citizens for Reagan, a lobbying group, has said it will call on its 100,000 members to cancel their HBO subscriptions.”

Worrell’s review: “At the heart of the drama is the relationship of two people who had no physical contact for 22 years and were long limited to the rare letter and visit. Together, Woodard, with her serene face and molten core, and Glover, an actor of towering force and compassion, transcend an otherwise ordinary hagiography. As a young bride, Winnie draws her strength from Nelson’s huge, healing hands cupped around her face. When she visits him in prison, Winnie, wearing native dress, brings to him the exalted dignity that she has painfully won. … Their eyes and smiles speak a silent reminder of apartheid’s terrible human cost.

“Unfortunately the filmmakers will not leave it at that. The movie is preachy and laden with speeches that hobble the narrative. Intricate political positions are drawn with a numbing oversimplification. All South African policemen are sadistic slobs with warty faces. Nelson is an immaculate martyr, always stoic. Winnie is a saint. But for all its flaws, Mandela does dramatize a country’s deadly turmoil. ‘South Africa has been locked off for so long,’ says Woodard. ‘I’m hoping for other movies. Mandela is just one star in a huge black sky.'”

Cry Freedom, 1987

The Oscar success of Gandhi must have made director Richard Attenborough an expert on holy insurgents in the Third World. Cry Freedom, a stately, schizophrenic epic of South Africa in the 1970s, as blacks groped toward liberation, ought to be the story of the Bantu activist Stephen Biko (Denzel Washington). The man was as close to being an authentic martyr as any revolution can claim: charismatic preacher of nonviolent resistance, champion of racial equality, steely victim of state sadism. He died in the arms of his torturers in 1977.

There is surely a film here, but Attenborough and his Gandhi screenwriter John Briley can’t find it. Meandering through a meadow of noble sentiments, they turn Biko into an angelic apparition; he is first seen swathed in blinding sunlight and last seen shimmering in the memory of his friend Donald Woods (Kevin Kline), a white liberal newspaper editor. Like Elba’s Mandela, Biko is portrayed as a passive hero, valued not for what he achieves but for what he endures. For all the strength and dignity that Washington invests in Biko, he is a placard masquerading as a character.

Once Biko dies, barely an hour into the film, Woods carries the narration; he plots his escape to any land that will issue his Biko biography. Woods must publish because Biko perished. The police threaten Woods’ cute family with errant gunfire and toxic T shirts, and the viewer is meant to recoil from these domestic atrocities. Of course they are horrid, yet their intended impact reinforces, in dramatic terms, the Afrikaners’ credo: white lives mean more. Piling on bogus suspense devices as Woods snakes his way toward freedom, Attenborough lets the venality of South African imperialism degenerate into a staid chase film: The Brady Bunch Flees Apartheid. Here as in so many of the films he has directed, Attenborough proves that the road to dull is paved with good intentions.

(Available for rental on Netflix.)

A World Apart, 1988

Set in the early 1960s, A World Apart places the comfortable life of 13-year-old Molly Roth (Jodhi May) in jeopardy when her leftist father Gus (Jeroen Krabbé) suddenly disappears, and her mother Diana (Barbara Hershey) is detained by the police. The movie sketches a poignant dilemma for Diana — a crusading career woman whose cause takes precedence over motherhood — and for the abandoned Molly, who dissolves into tears as any child would if her beloved parents were to vanish suddenly and ominously.

Shawn Slovo based her script on 117 Days, the autobiography of her mother Ruth First, whose Latvian-immigrant parents help found the South African Community Party, and who with her husband supported the outlawed ANC. In 1963, Ruth was the first white woman to be imprisoned under South Africa’s 90-Day Act. Exiling herself to England and then Mozambique, she was killed when she opened a letter bomb sent by the South African police.

Directed by the renowned English cinematographer Chris Menges (The Killing Fields, The Boxer), and filmed, like Cry Freedom and A Dry White Season, in neighboring Zimbabwe, A World Apart is plodding, not thrilling, in its blurred outline of the politics of resistance, but comes to human life in the mother-daughter dynamic. The movie took the 1988 Cannes Film Festival by storm, winning the Special Jury Prize (second place) and an award for actresses Hershey, May and Linda Mvusi.

A Dry White Season, 1989

The late ’80s offered annual apartheid movies, all about white people suffering at the hands of the white-racist state. (Oh, and blacks too.) This one was different, in that its director and cowriter Euzhan Palcy was a black woman from Martinique. With A Dry White Season, based on the novel by white South African André Brink, Palcy became the first black woman to direct a major-studio feature film. She also lured Marlon Brando out of an eight-year retirement to play a sympathetic lawyer, paying him union scale for a cause he believed in and a film that, as TIME’s Richard Schickel wrote, “stirs you to outrage.”

In 1976, South African school-teacher Ben du Toit (Donald Sutherland) lives cozily with his nice family and his vague belief that any injustices toward blacks are matters of botched paperwork. At the pleading of his gardener Gordon Ngubene (Winston Ntshona), whose son disappeared during the recent Soweto protests, du Toit does a citizen’s duty and investigates. He finds that the bureaucracy is, in Schickel’s words, “a strangely imperturbable menace. Searching for his son, Ngubene is also arrested; father and boy are tortured and then murdered in prison. And because Du Toit continues to seek justice on their behalf, he is himself victimized by state terror that is the more frightening because of the bland face with which it covers its institutionalized psychopathy. Du Toit is subjected to steadily escalating harassment. Eventually he loses his job and his wife (Janet Suzman in a good, dour performance), and he must deal with the fact that his daughter is willing to betray him to the police. …

“[T]he best thing about A Dry White Season is that it does not practice unconscious apartheid. Our attention may be focused on the political education of Ben du Toit, but the Ngubene family is well particularized and their torments set forth unblinkingly, not to say horrifically. And Ben is provided with a guide to the realities of life on the other side of the color line: the tough, suspicious, ultimately compassionate taxi driver named Stanley (Zakes Mokae). He is a man who turns up in surprising places in unpredictable moods. He provides the bestartlements that shake Du Toit, who is appropriately all stunned introspection.

“If Du Toit is the white audience’s surrogate, Stanley must be director Euzhan Palcy’s surrogate. Imparting energy and waywardness to her film, he helps give it the pulse of popular fiction without in any way diminishing its moral seriousness.”

(Available for rental on Netflix.)

District 9, 2009

Millions of space creatures — icky insect beasts that looks like giant shrimps, and with wriggling worms where their noses might be — have come to Johannesburg. And the government, which calls the creatures “prawns,” responds as the old apartheid regime might have to any influx of what it deems illegal aliens: locks them up in a sprawling area called District 9. The film’s title is a play on District Six, a vibrant mixed-race area of Cape Town that was declared whites-only in 1966, after which 60,000 of its residents were forcibly removed.

That’s a weird political subtext for a sci-fi movie produced by Peter Jackson and aiming to be the summer blockbuster thrill ride of 2009. But South Africa-born director Neil Blomkamp didn’t cringe at the genre collision that is District 9. “On one side of my mind you have this place with a crazy racial background, and on the other side of my brain you have this science-fiction geek,” he told TIME. “And then one day the two just mixed, and I decided I wanted to do science fiction in South Africa.” Writing the script with Terri Tatchell, Blomkamp became aware “that all these very serious topics about racism and xenophobia and segregation would start to shine through the science-fiction-esque veneer.”

Evicted and imprisoned, deprived of their rights, the aliens could be the Palestinians in Gaza, the detainees in Guantánamo or, transparently, black South Africans for the 46 years of apartheid and, in effect, for centuries before. Whites seem to run the country, the corporations and the media, much as they did under apartheid — and, to a lesser extent, today. And as in so many movies more explicitly about apartheid, a white South African (Sharlto Copley) emerges to get his consciousness raised. The difference is that, this time, the hero gets infected with some alien gookum, and his arm turns into a prawn-like claw. It’s his scarlet letter, his Star of David jacket patch: the signal to authorities that he’s been corrupted by idealism, and to audiences that he’s seen the light.

Quiz any fanboy about his favorite apartheid movie and, if he knows what apartheid means, he’ll say District 9. Made for thrifty $30 million and grossing more than $200 million worldwide, Blomkamp’s film made its satirical points within a teeming, propulsive, funny framework. It’s the ultimate thrill-ride parable that even Nelson Mandela, who for much of his iconic life had little to smile about, might enjoy. Or maybe not. So far as we known, his only public comment on the film was: “I saw District 9.”

(Available for rental on Netflix.)