Henry Louis Gates Jr. attends the "The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross" on Oct. 16, 2013 in New York City

It’s been a busy week for famed historian Henry Louis Gates Jr., one of the foremost scholars on black history and the director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African American Research at Harvard University. He served as a historical consultant on 12 Years a Slave, which premiered on Friday. And his new six-part documentary series, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, debuts tonight (Oct. 22, 8 PM ET) on PBS.

TIME sat down with Gates to discuss both projects and the portrayal of African-American history in film.

How did you come to be a historical consultant on 12 Years a Slave?

I got a call from Jeremy Kleiner, one of the producers. And I had been a consultant before, of course, to Steven Spieldberg for Amistad. And I was shocked; I was delighted that they were making a film out of [the book], because I don’t think anyone had ever made a feature film out of a slave narrative before.

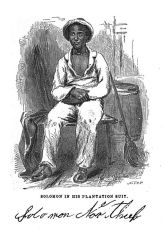

There were 101 slave narratives published between 1760 and 1865. And a slave narrative was an autobiographical memoir written by someone who had been a slave and escaped to the North. But of that 101, the only one describing the experiences of a free Negro who was kidnapped and then escaped was Solomon Northup. So I thought that was fantastic. And I said yes, so that was it.

As a historical consultant, what kind of things are you asked to do?

I read the script for accuracy, and then answer any questions that come up. I had an hour-long conversation with [12 Years a Slave director] Steve McQueen near the beginning of the production.

A lot of questions remain about Solomon Northup. Nobody knows what happens to him. It’s so strange. He becomes the best-selling black author in America in 1853. His book [Twelve Years a Slave] sold better than Frederick Douglass’ slave narrative, which is amazing to think about. It was dedicated to Harriet Beecher Stowe, was published a year after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and broke all kinds of publishing records. It sold 11,000 copies in the first month. Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass sold 756 copies in its first year, to put that in perspective.

And then there were two stage versions of the story. In the first, Northup played himself. So he was a superstar. He became a lecturer on the anti-slavery circuit; he aided other slaves in the Underground Railroad. And then he just disappeared.

I saw the 12 Years a Slave this week, and I felt like I hadn’t seen anything like it before. The realism and the brutality were very intense. I was wondering if you could talk about how the depiction of slavery in film over the years. How have we gone from Gone with the Wind to something like this?

Americans tend to have amnesia about historical events in general, but this is particularly true about the Civil War. And it’s obvious why–it was the most traumatic episode in American history with 750,000 Americans killed in a four-year period. Deep trauma there.

So after Reconstruction ended in 1876, there was an attempt to sanitize the war… The significance of the freedom of the slaves or the contribution of the black soldiers, whom Lincoln said actually won the war, manifested itself in Birth of a Nation in 1915, D.W. Griffith’s explicitly racist account of the birth of the Klan and the evils of Reconstruction. And that continued at the dedication of the Lincoln Monument—-they didn’t allow black people there.

Slavery and plantation life in the South came to be sentimentalized or romanticized, and the most graphic example of that, of course, is Gone with the Wind (below). It’s been a long process of trying to recuperate slavery from the fabulists who wanted to sentimentalize slavery.

I think that Amistad was the best film ever made about a slave rebellion. I think that Django Unchained was the best postmodern take on slavery. And the most realistic account of slavery in a feature film, without a doubt, is 12 Years a Slave. And it’s no accident that it’s a film done by two black people: a black director who’s black British of West Indian descent, and John Ridley, an African-American. And it’s a refreshingly honest depiction. What I like about it is that they followed an actual account of a black man who was a slave.

When did pop-culture depictions of the Civil War and slavery begin to move away from romanticized portrayals?

It started because of black studies departments, I think, which were born in 1969. And you had historians writing about slavery like John Blassingame who wrote The Slave Community, which the Oxford Press published in 1972. And that was the first time that any historian had used slave narratives as a way to write about slavery. Heretofore, historians had largely used the testimony of the planters. What’s that about? Well, they said the slaves couldn’t be objective–as if the planters could… So it really was the ‘60s, after Black Power and the birth of black studies when there were pressures on historians to tell the story of slavery from the point of view of the slave.

When I saw 12 Years a Slave, I was struck by the violence — how casually so many of the white characters would use violence. It was difficult to watch. In your opinion as a historian, how does a filmmaker find that line between being true to a story and maybe being so true that people will forgo seeing the film?

12 Years a Slave actually minimizes the depiction of violence. Slavery was a brutal, violent, sadistic institution. And I think that Steve McQueen showed remarkable restraint. It just hints at how violent slavery was… You can’t depict it and not show violence. That would be Gone with the Wind. But if you’re depicting it, there is a lot more violence in Solomon Northup’s slave narrative than there is in Steve McQueen’s film.

And I thought focusing on the bizarre relationship between Epps and Patsey was successful. Epps obviously loved her, and hated himself for loving her. He couldn’t deal with it, and so he beat her. That’s why he goes crazy out of jealousy when she disappears to go get the soap. One of the most amazing and successful things the film does is show the way that slavery dehumanizes the master as well as the slave.

What would say to people who want to see the movie but think they might be put off by the violence and brutality?

Oh, I don’t think it’s so hard to watch. They should go see it. Alan Dershowitz called it the African-American Schindler’s List. We have to see it. But I’m a scholar of slavery, so I would tell them it only touches on the actual violence and trauma that black human beings experienced for 300 years under slavery.

Turning to your new documentary series on PBS, The African Americans, why is this an important project [retelling 500 years of African American history] to take on now?

It’s a year of amazing anniversaries: it’s the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. It’s the 150th anniversary of Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. And it’s the 500th year of the arrival of the first African in the United States. That would be Juan Garrido. He was a black conquistador. He was free. And he arrived in Florida with Ponce de Leon, looking for the Fountain of Youth, just like the white guys. Most people don’t even know about him. And secondly, it’s the year of the second inauguration of the first black president, so it seemed like the perfect year to do it.

But in addition, it arrives at a time when we have a paradox in the black community: we have the best of times, and we have the worst of times. We have the largest black upper-middle-class in history, but we have the largest black male prison population. 70% of all black children are born to mothers out of wedlock, and about 35% of all black children live at or beneath the poverty line. So it’s like we have two nations within the black community. So how did we get here?

You said that you always dreamed of being a filmmaker. Has there been a film or documentary that has had a particularly strong influence on you?

Oh, yes. My whole introduction to African American history was through a Bill Cosby documentary from 1968 called Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed. Iit was an epiphany. A year later, I found myself at Yale, and the first course I enrolled in was William McFeely’s survey course on African-American history. And so I was hooked. I’d been raised to be a doctor, but by this time, man, that ship had sailed. Took me years to admit it to myself and anybody else, but I really knew because of those two experiences that what I wanted to be was a scholar of African-American studies. And the deeper fantasy was to be a filmmaker.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jtI-ItO6LE]