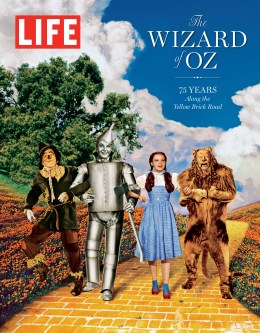

This is the third in a five-part series, adapted from an essay in LIFE’s The Wizard of Oz: 75 Years Along the Yellow Brick Road, published by Time Home Entertainment and available on newsstands this week.

Behind the intense and eternal entertainment value of this ultimate studio production, The Wizard of Oz endures because it speaks in subtext to so many segments of the audience. Put baldly, it is a multiple act of empowerment for traditionally powerless groups. We’ll try to analyze these four aspects without strangling all the fun out of the movie.

* * *

KID POWER. Here’s how a child might tell the movie’s plot: Dorothy the orphan girl lives — subsides, actually — on a Kansas farm surrounded by stern, oafish, duplicitous or downright sadistic adults. Em, the woman who runs the place, radiates all the grace of a prison matron while bossing her weaker husband Harry and her three feckless farmhands. With no friends her own age, Dorothy must confide her dreams of a land over the rainbow to her dog Toto. But now a truly evil adult, Miss Gulch, wants Toto totaled — a verdict that sends sobs like stabs through the girl’s heart. To protect her pet, Dorothy runs away from home. On the road she meets Professor Marvel, who falsely hints that her aunt is dying. Her niecely responsibility trumping all hope of escape, she rushes back to the farm, where a ferocious wind whisks her out of Kansas and, voilà, into a Technicolor land of sunshine, lollipops and rainbows. Also wicked witches, soldier monkeys and poisonous poppies. Still, the place is less like the life sentence of Kansas than like a DayGlo exclamation point. Free at last!

We grant that Dorothy didn’t go to Oz voluntarily. For this young pioneer, a cyclone-propelled house was her wagon train. Yet when she got there, she behaved bravely and selflessly. In the Baum book, Oz is a real place, and Dorothy was lucky to see its wonders. In the MGM film her trip is portrayed as a dream, but that doesn’t diminish the girl’s accomplishment. It means that she is an artist of surpassing creativity. Instead of discovering Oz, she invented it.

This Wizard movie differed from other children’s stories in several ways. The earliest Disney animated features, for example, painted childhood as an unrelenting nightmare, from which the young protagonists eventually escaped to a happy ending more by luck than by heroism. The vivid portrayal of childhood misery allowed kids to see Pinocchio or Dumbo as extreme cases from which they could distance themselves; their lives weren’t that bad.

(FIND: Pinocchio and Dumbo on the all-TIME Top 25 Animated Features list)

That’s Dorothy’s life on the farm: it isn’t tragic, just dull and painful, like a toothache with no dentist for miles. In other words, the recognizable existence of a desolate kid. And Oz, for all its mortal hazards, offered Dorothy an adventure through which she could brandish the love and nobility that no one thought to ask her to display at home.

Some classic children’s fables painted life as a Museum of Surrealist Art, a dreamscape for the underage protagonist to wander through. Lewis Carroll’s Alice, the Wonderland girl who had appeared in print 35 years before Baum published his first Oz book, gazed at the frantic charades of the Mad Hatter and the Red Queen through the looking glass of her amused passivity. Dorothy, though, is an activist — at first by default, when her house crushes the Wicked Witch of the West’s sister, and then by defying death on a children’s, a child’s, crusade to find the Wizard and somehow earn her passage back home.

(READ: TIME’s 1945 essay on Lewis Carroll and his Alice)

The crafty malevolence of the WWW, the fuming and stalling of the Wizard, the winsome failings of the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Lion — none of these can derail Dorothy’s commitment to her quest. Let adults be corseted by convention and compromise; this girl has more brains, heart, courage and wisdom than all the Wizards and Witches combined. As Salman Rushdie wrote in a 1994 essay on the film, “the weakness of grown-ups forces children to take control of their own destinies.” A little child shall lead them.

At first, MGM took that Isaiah quote quite literally: the studio brass hoped to borrow Shirley Temple, then nine years old and the biggest star at 20th Century-Fox, to play Dorothy. Though Temple was close to Dorothy’s age (Baum biographer Katharine M. Rogers calls her “a child of about six”), the casting seems daft. A child, no matter how precocious, would be no match for Dorothy’s adult adversaries. She couldn’t charm them, which was Temple’s strategy in her Fox films; she must defy and defeat them. And how could that cinemoppet (TIME’s term) locate the hope and ache that Garland invested in “Over the Rainbow”? MGM’s awarding of the role to the 16-year-old Judy proved to be one of Hollywood’s smartest casting choices.

(READ: Our 1936 Shirley Temple cover story by subscribing to TIME)

* * *

WOMAN POWER. Was L. Frank Baum a feminist, at a time when black males were legally free to cast a vote but women of any color were not? He was indeed. As Meghan O’Rourke noted in a 2009 Slate essay, “Baum, who publicly supported women’s right to vote, was deeply affected by his beloved, spirited wife, Maud, and her mother, Matilda [Gage], an eminent feminist who collaborated with Susan B. Anthony and publicized the idea that many ‘witches’ were really freethinking women ahead of their time. In Oz, Baum offers a similarly corrective vision: When Dorothy first meets a witch, the Witch of the North, she says, ‘I thought all witches were wicked.’ ‘Oh, no, that is a great mistake,’ replies the Witch of the North.” O’Rourke added that, “In sequels, Oz’s true ruler … turns out to be a girl named Ozma, who spent her youth under a spell — one that turned her into a hapless boy.” The Wizard is just a regent; this empire has a Queen.

(READ: the 1960 astronomy probe called Planet Ozma)

Baum’s biographical details aside, the Oz of the book and the MGM movie is a full-fledged matriarchy. On the Gale farm, the strongest figure is Auntie Em. In Oz, Glinda the Good Witch presides over Munchkinland. The Wicked Witch of the West is the Castro and the Che of her insurgent campaign — the usurping politician and the crafty military commander, lording it over the monkeys and the male guards.

One of the Wizard screenwriters’ signal inspirations was to promote the WWW from minor villain to Dorothy’s nemesis: a dual-identity bitch-witch who rode her bicycle across Kansas, and her broom above Oz, brimming with threats to kill Toto, set the Scarecrow on fire and plant a swarm of bees in Tin Man’s hollow chest. Finally vanquished, she is stirred to bilious wonder: “Who ever thought a little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness?” Her last lines — “I’m melting! I’m melting!” — are capped with a final, self-pitying profundity: “What a world, what a world!” Her spirit, though, lived long enough to see a showbiz world that both treasured villainy and set it to music, when her poignant, arguably heroic backstory was told in Wicked. (One person who didn’t romanticize the WWW was Judy Garland, who later said that her own mother, Ethel, “was no good for anything except to create chaos and fear. She was the worst — the real-life Wicked Witch of the West.”)

(READ: Richard Zoglin on the Broadway musical Wicked)

The little girl is Dorothy, devising schemes to infiltrate the Wicked Witch’s castle and eventually killing her, while acting as the efficient surrogate mother of her three hapless friends. The only adult male in the Kingdom is the Wizard, who also appears in the guise of a palace guard, a coachman and a gatekeeper. Yes, this Great and Powerful Oz is the beneficent granter of all (well, most) fervent wishes; but the reign of the movie’s one “strong” man is a ruse. And at the end he abdicates, in a balloon, leaving a flummoxed Dorothy in charge, with the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Lion as her cabinet. If the homesick girl hadn’t been told to click her heels, she’d still be the Wizardess, waiting for Ozma.

Gone With the Wind, MGM’s (and Fleming’s) other big 1939 film, was also predominantly a woman’s movie, with Scarlett, Melanie and Mammy fighting to sustain their home and tend the children. But sexy Clark Gable did tip the scales toward a gender balance. In The Wizard of Oz, the males are bumbling or bogus. The women of Oz perform all the magic, for good and ill. And one of them, a young stranger, saves the kingdom.

* * *

PROLETARIAN POWER. Virtually every adventure story relates a rebellion of the underdog against the ruling class; few movies find the one percent wonderful. Knowing that the poor filled more theater seats than the rich, the makers of The Wizard of Oz made its chief villain a wealthy landowner.

Miss Gulch is not only a “sour-faced old maid,” in the words of Hickory (later the Tin Man); she is also the richest person in this part of Kansas. The film opens with Dorothy rushing urgently home after an (unseen) encounter with Gulch, who whacked Toto after the dog toyed with her cat. Soon Gulch cycles over to the Gale farm with a warrant for Toto’s apprehension and demise, which prompts Auntie Em to uncork a little of Ma Joad’s vinegar from The Grapes of Wrath: “Just because you own half the county doesn’t mean you have the power to run the rest of us!” Oh yes, she does, because, in this Kansas, money talks; Gulch presumably exerted her financial and political influence to secure the warrant. The spiteful spinster essentially dognaps Toto — an act that triggers Dorothy’s escape, and possibly the wrath of the cyclone that lands her in Oz, where Gulch awaits as the WWW.

(READ: TIME’s 1940 Cinema review of The Grapes of Wrath)

We’ve said that Auntie Em, Uncle Harry and the three farmhands — Dorothy’s ostensible authority figures — shower little parental love and guidance on her. She must find those qualities in Oz. Glinda has them in abundance, but she’s not around much, like a charismatic relative who appears only at whim (in a floating soap bubble). The Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion are Dorothy’s boon companions but also her emotional dependents; she must pick them up. Nor can she trust Oz’s supreme authority, the Wizard, who uses her as a one-girl counterrevolution, sending her on a suicide mission to steal the Wicked Witch’s broomstick. Besides, as we eventually learn, the Wizard of Oz is a fraud.

“I am Oz, the great and powerful!” he thunders through his sulfurous TV screen. And the girl replies, “I am Dorothy, the small and meek.” In Oz, the meek will not inherit the earth; she must seize it. Grave peril forces a common farm girl to find the unique heroism inside her. Back in Kansas, Dorothy didn’t think of herself as extraordinary, only bereft and frustrated; her intuitive reaction to danger was flight. Finally, she learns to fight, in a new land whose threats don’t sap her but give her strength.

(FIND: Oz among the all-TIME Top 10 Most Beloved Wizards)

That was the movie’s mixed message to its Depression audience: You can fulfill your fantasies by standing up for your rights — but to get there, you have to move. Leave the barren Plains! Crawl out of that Dust Bowl! Find the American Dream in the Oz of California, and the Emerald City of Hollywood.

* * *

GAY POWER. Another group to which The Wizard of Oz spoke, at least in semaphore, was homosexual men. In the decades before Gay Liberation, when their natural sexual proclivities were deemed crimes in America, they took heart in the movie’s tale of people cloistered and repressed in dreary Kansas who reveal their full eccentric glory in Technicolor Oz. The Gale farm is real life; Oz is show business! To become a star, Dorothy goes not to Broadway’s Great White Way but to the Emerald City. There she is transformed from a helpless child into the Munchkins’ savior princess, and the handymen come out as the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion.

In conventional manliness, the three amigos of Oz are not exactly the Fellowship of the Ring. Comic relief more than staunch warriors, they lack, respectively, a brain, a heart and “the noive.” All are clinically reliant on Dorothy and easily intimidated — especially the Lion, who confesses, with mincing gestures and a toss of his blond curls, “Yeah, it’s sad, believe me, Missy, / When you’re born to be a sissy,” and “I’m afraid there’s no denyin’ / I’m just a dandy lion.” Yet Dorothy proclaims them “the best friends anybody ever had” (perhaps because her only other best friend couldn’t talk; Toto only barked). These friends of Dorothy join her on the Yellow Brick Road in their collective search for the godlike Wizard. Plus they get to sing and dance. They could be Oz’s Village People.

(READ: Dan Goodgame on Dorothy, Gays and West Hollywood in 1985)

Not long after the film’s release, gays began employing the phrase “Friend of Dorothy” as a code for introducing themselves to other men without risking assault, arrest or blackmail. The name stuck; a half-century later, cruise-ship schedules would announce meetings for Friends of Dorothy, or FOD, as a delicate way of indicating, without frightening the straights on board, that gays were welcome to socialize.

But not everyone was in on the acronym. In his 1994 book Conduct Unbecoming: Gays & Lesbians in the US Military, Randy Shilts reported that in the late 1970s or early ’80s the Naval Investigative Service, unaware of the phrase’s meaning, “believed that a woman named Dorothy was the hub of an enormous ring of military homosexuals… [they] prepared to hunt Dorothy down and convince her to give them the names of homosexuals.” Aside from its hilarious and cruel cluelessness, this Dorothy caper makes the definitive argument for allowing gays in the military — at least in the NIS.

(READ: Richard Lacayo on the New (1998) Gay Struggle)

As Garland aged from sweet teen to tragic diva, before her death at 47 in 1969, gays embraced her as their den mother, “Over the Rainbow” as their song and the MGM film as their story. John Waters, onetime naughty filmmaker (Pink Flamingos) and the all-time Cardinal of Camp — or at least the Dandy Lion — has given this lavender précis of the movie’s plot: “Girl leaves drab farm, becomes a fag hag, meets gay lions and men that don’t try to molest her, and meets a witch, kills her. And unfortunately — by a surreal act of shoe fetishism — clicks her shoes together and is back to where she belongs. It has an unhappy ending.”

Waters knew, as we all do, that Dorothy and her Friends belonged not in Kansas but in Oz; that’s where they can flounce and flourish. And speaking of shoe fetishism: In 2005, one of the few surviving pairs of the movie’s ruby slippers was stolen from Garland’s childhood home in Grand Rapids, Minn. (which was by then the Judy Garland Museum). On his late-night show, David Letterman deadpanned that “The thief is being described as ‘armed and fabulous.’”