The first Dear Sugar letter I read was from a woman who called herself Stuck. She had had a miscarriage when she was six months pregnant. Her doctor told her the pregnancy might have failed in part because she was overweight. She was caught in a spiral of grief and blame, and wrote to Sugar, the advice columnist at TheRumpus.net, to ask how she could stop feeling so ashamed and alone. The letter was heartbreaking, and so was Sugar’s response, which used her signature method of telling stories from her life to illuminate the problem.

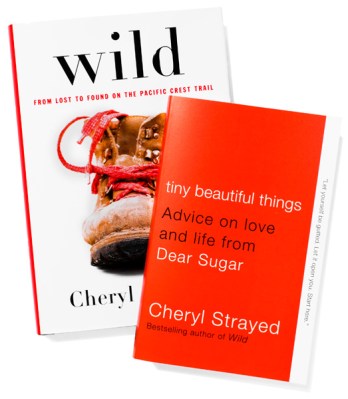

This February, Sugar was officially revealed to be Cheryl Strayed, a writer based in Portland. She’s having a busy year. Her memoir Wild, the story of her solo trek along the Pacific Crest Trail in 1995—when she was 26 and trying to recover from the loss of her mother to cancer and the breakup of her marriage—came out in March and earned rave reviews (notably from the New York Times’ Dwight Garner, who wept over it). A selection of her Dear Sugar columns called Tiny Beautiful Things scheduled to be released in July. And two weeks ago, Oprah announced the relaunch of her book club, with Wild as the inaugural pick.

This February, Sugar was officially revealed to be Cheryl Strayed, a writer based in Portland. She’s having a busy year. Her memoir Wild, the story of her solo trek along the Pacific Crest Trail in 1995—when she was 26 and trying to recover from the loss of her mother to cancer and the breakup of her marriage—came out in March and earned rave reviews (notably from the New York Times’ Dwight Garner, who wept over it). A selection of her Dear Sugar columns called Tiny Beautiful Things scheduled to be released in July. And two weeks ago, Oprah announced the relaunch of her book club, with Wild as the inaugural pick.

I visited Strayed at her home in late May. I was intrigued by the combination of Wild and Tiny Beautiful Things, two deeply contemplative books, written in very different forms. We had breakfast with her family, followed by a conversation about her writing life, from which this Q&A is edited. (There’s also a piece in this week’s TIME, which you can read here.)

Radhika Jones: Tell me about taking on Dear Sugar.

Cheryl Strayed: I had just sent off the first draft of Wild to my editor, Robin Desser at Knopf. When you finish a first draft of a book, you have this little period of time before your editor comes back at you with all these notes when you get to feel like, my book is done! So I was in that lull, and I received an email from Steve Almond, who is a friend of mine, and he said, I write this column called Dear Sugar, I don’t want to do it anymore, do you want to do it?

How long had he been doing it?

He’d been doing it a couple years. I said yes, and then instantly questioned that, because, as a writer, there is constant struggle between trying to figure out what to do for free and what not to do for free, especially in this age of literary websites. So I questioned all these things, and there was just this feeling inside of me—my husband even sensed it when I was talking to him about the column, he said, ‘You’re sparked aren’t you?’ I thought, Well, I’ll just try. I’ll just see what it’s like to write a column.

Reading the galley, you get a little bit of the sense of an epistolary novel, because the quality of the letters is so high.

Early on, people were saying, people at The Rumpus must write these letters. I swear to God, those are letters written by actual people who just email me. It’s not like this committee of people who are conjuring scenarios. The letters are very lightly edited—in fact, hardly touched at all. I’ll fix grammar, or if somebody is repeating themselves. But you know, mostly I’m trying to keep people’s voices in there, the things they say about themselves. And in the column, I often use their language to answer them. I say, ‘You said.’

I do get letters that are poorly written too. Quality of writing isn’t one of the criteria I use to pick a letter, but I will say sometimes, if people don’t really articulate their problem, if I’m going to have to do too much guessing or make too many assumptions, I steer clear.

(MORE: Brief History of Oprah’s Book Club)

Do you see yourself in a tradition of advisers or essayists?

When I began writing that advice column, I didn’t know anything about advice columns beyond the occasional Ask Amy or Dear Abby. I didn’t read advice columns in any kind of intentional way.

I do feel like my advice, as I write it, is almost more in the tradition of the personal essay. And yet there’s no way around the fact that I’m using the direct address. In an essay, I don’t. When you read “Munro Country,” or any one of my essays, implicitly you’re listening to me, implicitly I’m talking to the reader, but not explicitly. Whereas in Dear Sugar I’m saying ‘you.’ You have this problem, you’ve written to me, I’m going to write to you, and a bunch of people are going to listen in. It’s like therapy in the town square. It amps up the energy and the power.

When I first started telling stories about my life in the column, I was like, Are people going to think that’s weird? I didn’t want people to think that I was telling stories because this is about me. You know how when you go to a friend, and you say you have this problem, and they immediately hijack the conversation, and you spend the whole time just talking about their problem? That was not my intent. My intent was—stories, poems, they have been my guiding lights. I thought, why not give others what I’ve received from other literary forms? And that is stories that move me and allow me to see myself more deeply, and to see the human experience more profoundly. I’m just using my life as a way of showing those things.

(LIST: All-TIME Top 100 Novels)

How long do you think you’ll do the column?

I certainly will for the next few months. Beyond that, what I might do—what I’m really feeling on a gut level—is not write a regular column, but every once in a while, like occasional essays. I want to write other things.

One of the things I loved about Wild was how you persevered through the physical damage you experienced on this hike. I just kept thinking about the toenails you lost. Did they come back?

The number one question I’ve gotten on my tour is, ‘Are your feet okay now?’ And they are. It took a few years for my toenails to be normal again, but they became normal. They had to slowly regenerate, and the toenail bed was quite damaged—I’m going to say three or four years. But now they’re normal.

I wonder if there are a lot of people trying to hike the trail.

Yes! People have already gotten out there. I’ve gotten so many emails, and I must say it’s so funny, because I’m thinking, Yes do it, this is great for you, and then thinking, Oh dear, what if something bad happens to someone? But you know, they’re inspired to do it.

It made me want to be outside, and it made me want to be silent and alone. But the quiet part of it is maybe more elusive now.

That’s the hugest way that the trail has changed. In ’95, there was not really an Internet—I mean, there was the Internet, but regular people weren’t on it. The first time e-mail was explained to me, I was standing on the Pacific Crest Trail. I’d met another hiker—she is just briefly mentioned at the end, I met these two women in central Oregon and hiked with them a bit—and one of them was an aspiring magazine editor. And she’s like, ‘There’s this thing, e-mail.’ She explains it to me: you write a letter, and then you press this button on your computer, so then this letter appears on your screen. I’m like, ‘So it’s like a Word document that appears on your screen?’ She’s like, ‘Yeah, kind of.’

Same with cell phones. One of the other hikers, he was asked by some cell phone company to carry a cell phone to see where the reception was. It was like a brick; it was gigantic. And he’s like, ‘I’m gonna ditch this,’ because of course he never got reception anywhere. But last summer I was hiking on the PCT and I tweeted from the trail, on my iPhone. People are carrying their digital books. We can go online now and read hundreds of trip trail journals.

(MORE: Modern Living: Ah, Wilderness!)

In the book you say that you were one paper short of finishing your undergraduate degree. When did you finish your degree?

In early 1997, I realized that I needed to do this. This was unfinished business, so I called the University of Minnesota and explained my situation. I said, ‘I was there, I graduated, quote-unquote in 1991, but really I didn’t finish a class, I have an incomplete. What do I need to do?’ The woman who answered the phone, she said, ‘All you have to do, Cheryl, is just take one class. It doesn’t matter what. Take one class, and I’ll OK it.’ And I said, I’ll take Latin 101, because I never had any Latin, and I was a writer, and I thought it would be interesting.

Again, this was ’97. The Internet was not as pervasive. So I did it the old-fashioned way, by correspondence. In the mail, by horse-drawn wagon, my teacher would send me these lessons each week, and I would do them. I’d send them back, and he’d give me feedback.

What are you working on now?

I started two things before the firestorm of Wild hit. One is a long essay called “Places We’ve Never Been,” and I didn’t realize this until recently, but it’s kind of a prequel to Wild, because it’s the first trip I took by myself. It’s me in my pickup truck driving around the American Southwest. When I was 23 I won a grant from the Jerome Foundation, a travel grant, to go research atomic history in the American Southwest, and visit my mother’s childhood home. She was an Army brat, grew up there, at least for part of her childhood. And I got this idea in my head, because I was trying to figure out, why did my mom get cancer and die? She wasn’t a smoker, and I thought, well, maybe it’s exposure to radiation, because they were doing aboveground nuclear tests there. So I went on this trip, and I had a futon in the back of my truck, and for six weeks I traveled all over and interviewed people who are downland activists. I had all kinds of adventures.

And I also started a novel that I’m really excited about. One of the main characters in the book is an astrologer. That’s something I know very little about, and I’m really interested in spending some time researching what is it to be an astrologer. I want to write about it in a way that’s not mocking, that’s sincere. So someday in my not too distant future, I’ll do one of those things, or both of them.

It must feel good to have success come at an age where you can absorb it, and just be thinking about, how do I want to challenge myself next.

Of course what I really wanted for my life was to be that 25-year-old wonder kid where everyone was like, my God, so young and so talented, and she got that million dollar book deal. Thank God I didn’t get it, because I think it would not have been good for me. By the time this has happened, that Wild has had this success, I’ve been beaten down by life, I’ve been beaten down as a writer. But I also have perspective about it.

I think that’s the way life really works, if we do it right, that we allow ourselves to be our resource. That’s why, these people who email me, I’m like, Go! Do it! This one woman went to hike the trail, and she emailed me and said, ‘I only made it three or four days, I ended up bailing out and coming back. It was just too hard for me; all these things came up.’ And the thing is, that wasn’t a failure. I know those four days were hard, and probably the hardest days. If I was alone out there, I would be uncomfortable about being alone, especially the first few nights. I’d be bored. I’d be a little uncertain. I’d have to tell myself, it’s OK, you’re not afraid. I would be regretting it. It doesn’t mean it’s a bad choice to do it. And it’s not like I’m this special brave person. We all are, if we decide to be.

READ: How Wild author Cheryl Strayed became the queen of advice in TIME