At the Plaza Hotel in New York the Beatles had basically been shut-ins, but in Miami, where they landed on Feb. 13, 1964, there was plenty of opportunity to soak in the sights. After being whisked past 7,000-10,000 screaming, marauding teenage fans at the airport to the grand, sun-washed Deauville Hotel on Collins Avenue, they immediately settled into the spirit of the place. They slipped into matching terry-cloth cabana outfits and hit the beach, attempting to seek out kids their own age. “It was a big time for us,” Paul recalled, “and there were all these lovely, gorgeous, tanned girls.” He whipped out his Pentax and began snapping photos of the comely flock, as well as the phalanx of armed motorcycle cops who stood nearby, at the ready.

The next morning, Feb. 14, the Beatles were set to have a Life magazine photo shoot in the hotel pool. For practical purposes, though, the Deauville couldn’t seal off the area from its other guests. Thus, the place was a mob scene, impossible to navigate. At the last minute the comedian Myron Cohen, who was on the same Ed Sullivan bill as the Beatles, phoned a friend who lived nearby and asked if some people could use her pool. A short time later, two convertibles pulled up to a nearby bungalow with the entire entourage spilling out of the seats. Despite a sudden cold snap that blanketed the city, Brian Epstein ordered them right into the pool.

As a reward, they were whisked off for an afternoon’s cruise aboard the Southern Trail, a 93-foot yacht with a full crew, owned by the sofa-bed magnate Bernard Castro. By midday the tropical sun had broken through, allowing them to take advantage of the vaunted climate. They went for a lazy group swim in the ocean. Later, Paul sat behind the yacht’s piano and banged out a few lines of their next single, “Can’t Buy Me Love.”

Even they knew that wouldn’t last long. By the time they docked in the bay marina, it was necessary to resume playing keep-away with the fans. Fortunately, they were in the hands of a resourceful cop, Sgt. Buddy Dresner, who had been assigned to head their security detail. With the Deauville entrances under siege, Dresner rented a Hertz truck and delivered the boys to the loading dock behind the hotel.

Hours of nitpicking sound checks left them hungry, and Dresner knew just what to do. He’d had a couple of days in which to observe their preferences. These boys needed some TLC, so Dresner asked them how they felt about a homecooked meal. It turned out that was exactly what they wanted.Dresner called his wife Dorothy and gave her the news. “How many are there going to be?” she asked. Buddy did the math; aside from the boys, there was their entourage—roadies, management, John’s wife Cynthia, sundry others. “Oh, about 21,” he replied.

Add to that Dresner’s own family. His wife didn’t bat an eye. By the time all the guests had made their way to the house, a feast was waiting: salad first, as Buddy had instructed, followed by roast beef, baked potatoes, green beans, peas—then dessert, strawberry shortcake. It was more than satisfying after a week of eating hotel food.

After their Sunday, Feb. 16 evening performance for Ed Sullivan, the Beatles still had nearly eight days in paradiseand wanted to sample itspleasures: to go out, experiencethe city, hit the clubs,unwind. Stashed in the back of a refrigerated butcher’struck, they decamped to a private estate on Star Island, an exclusive celebrity enclave in South Beach, with a guardhouse that offered asemblance of privacy. The owner of the househad left the place well provisioned. The Beatlesswam in the heated pool, water-skied and fishedoff the dock. There were other shiny toys at their disposal,including a speedboat, which Ringo took for aninaugural spin.

There were still the requisite obligations—anin-depth interview with the Saturday EveningPost ; a couple of phoners to important disc jockeys,including one to placate American Bandstand’s Dick Clark, during which the Beatlesgratefully acknowledged their reception in theStates.

New York had been an eye-opening experience, but Miami lay even furtheroutside any world the Beatles had ever known. For a bunch of boys who hailed froma gritty, impoverished industrial port, having played gloomy Hamburg and rainyLondon, Miami was a whole other universe—sun and fun, slick borscht-belt showbiz,yachts, drive-ins, grilled-cheese sandwiches. This leg of their American journeyintroduced them to a culture radically foreign to their experience, from insulting comedian Don Rickles to soon-to-be legend Cassius Clay. Did it change them? Not essentially. They went back home and remained the Beatles, cranking out prototypical Beatles songs like “A Hard Day’s Night” and “I Feel Fine.”

The Beatles knew deep down that they werethe Lads From London, and while they wanted to conquerAmerica, they weren’t about to become Americanized.Determined to remain true to themselves, on Feb. 21they boarded a Pan Am flight with a stopover in New York,and headed home.

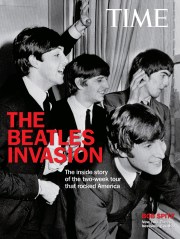

This is the seventh installment in a series of excerpts from the new TIME book, The Beatles Invasion: The Inside Story of the Two-Week Tour That Rocked America, by Bob Spitz. Copyright 2013, Time Home Entertainment. Available wherever books are sold.