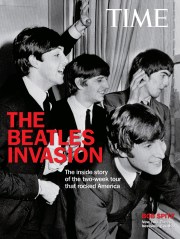

The Beatles perform at Carnegie Hall in New York City during their 1964 US tour.

The unrelenting spotlight and grueling schedule were starting to wear on the Beatles. The constant encroachment and the extraneous obligations were exhausting. There were none of the boundaries they were used to in England.

On the morning of Feb. 12 they were put on a slow-moving train rattling up the East Coast, while manager Brian Epstein and his staff flew the shuttle back to New York. The boys, for their part, were chaperoned by an entourage of journalists who refused to give them a moment’s peace. “We enjoyed it in the early days,” George recalled, but “the only place we ever got any peace was when we got in the suite and locked ourselves in the bathroom.”

But that wasn’t about to happen anytime soon. The platforms were mobbed with several thousand fans when the train pulled into Pennsylvania Station. At the last minute, the cops detached the Beatles’ car from the rest of the train and diverted it to an isolated platform. A plan to take them up a special elevator was foiled by fans, so the boys charged up the closest set of stairs and jumped into a taxi idling on Seventh Avenue.

They were overdue for rehearsal at Carnegie Hall, where they were scheduled to appear twice that evening.

Even for the Beatles, Carnegie Hall was no ordinary gig. The place was a shrine; the name alone humbled any musician. But if the Beatles were in awe of entering the place, they didn’t show it. They relaxed in the prestigious green room just behind the stage, chain-smoking American cigarettes and drinking lukewarm tea, completely unfazed by the remarkable surroundings. On the walls just outside hung autographs of the hall’s most famous denizens: Ravel, Rachmaninoff, Mahler, Caruso, Pons, Handy, Cliburn, Casals, Rostropovich, Callas. Until that night, Bill Haley & the Comets and Bo Diddley had been the only rock ’n’ roll acts to set foot in Carnegie Hall. Apparently, its board of directors didn’t dig the groove. Neither Elvis nor Buddy Holly was granted a date, not even the Everly Brothers.

As the lights went down, the 2,900 concertgoers, most of them teenage girls, delivered a protracted scream that never let up for the duration. “It was mayhem,” recalled Dan Daniel, a longtime local DJ. “It was the most piercing, uncomfortable sound I’d ever heard.

The five of us held our hands over our ears. Fifty years later, my ears are still ringing.” The manic response had a similar effect on the Beatles. You could see it in the way they comported themselves onstage. Their timing seemed herky-jerky; they were slightly off stride. There was no way for them to connect through the impenetrable wall of screams. Meanwhile, no one in the seats could hear a word they sang. It was absolute “bedlam” in that place, according to the editor of Melody Maker, who covered the show in an article aptly titled “The Night Carnegie Hall Went Berserk.” A wild horde tore up and down the aisles. Girls lobbed a jungle’s worth of stuffed animals. It was a free-for-all, which the ushers watched with goggle-eyed horror.

The Beatles were used to such behavior. They’d seen it before—and worse—back home, but their music always managed to upstage the chaos. Not this night. If at first they were amused by the antics, they grew frustrated by the audience’s refusal to listen. After the seventh song, John had had enough. The New York Times reported that he throttled the mike, “looked the audience sternly in the mouth, and yelled, ‘Shut up!’ ” Not that it did him much good. “Yells and shouts rose to an ear-shattering volume,” Melody Maker noted. After a concert lasting only 34 minutes—as with an identical show immediately following it—the Beatles bowed, dropped their instruments and headed for the wings.

This is the sixth installment in a series of excerpts from the new TIME book, The Beatles Invasion: The Inside Story of the Two-Week Tour That Rocked America, by Bob Spitz. Copyright 2013, Time Home Entertainment. Available wherever books are sold.