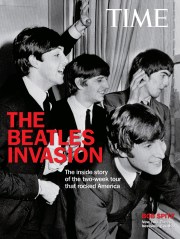

The Beatles perform at the Washington Coliseum on February 11, 1964 in Washington, D.C.

On Feb. 11, two days after their Ed Sullivan debut, the Beatles really started to mix it up with the natives. They were due to give an evening performance in Washington, D.C., their first concert in America. Plans had been made to fly into the capital, but a flash snowstorm early that morning crippled the New York airports, forcing a last-minute change. It was decided to transport them by train instead. A private sleeping car was chartered expressly for the trip, not the glamorous Orient Express–style accommodations that such a conveyance might suggest but a tatty vintage boxcar, stale from cigarette smoke and outfitted with bench seats

whose springs had seen better days. Neither glamorous nor private: what seemed like most of the New York press corps pushed into the car along with the Beatles. There was nowhere for the boys to hide. For nearly four hours, as the train chugged south, they were at the mercy of anyone who imposed. But the Beatles took it all in stride. They chatted and mingled at their uproarious best, so different from the way stars are now—distant, with their army of handlers.

John and Paul sauntered through the train, interacting with the paying passengers and posing for pictures.

D.C.’s cavalcade of well-lit monuments entertained the four Beatles as they made their way toward the Washington Coliseum. It was an enormous redbrick building in the heart of the city, an outdated arena that no longer hosted prestigious events. Still, it was the largest venue they’d ever played—with the promoter jamming 2,500 temporary seats up to the lip of the stage to accommodate 8,100 fans. The boxing-match layout dictated that the Beatles would perform in the round, meaning on a central platform with the audience on all sides.

The arena felt as if it were under attack, and from where the Beatles stood, the situation looked perilous. There were no barriers between them and the audience. Fans practically spilled onto the stage. Still, from the opening bars of

“Roll Over Beethoven,” they let it rip, harnessing the elements of chaos around them into a powerhouse performance, a selection of all-out rockers with the volume cranked as high as possible, urged on by the fight-crowd atmosphere.

For a first live American show, it was nothing short of a smash. The Beatles left the Coliseum elated—but wounded nonetheless, nursing a speckling of welts from airborne jelly beans. During an interview in England, George had casually mentioned that he liked eating Jelly Babies, the soft, squishy candies wrapped in cellophane, and fans there started the practice of throwing them onstage at shows. Something, however, got lost in the translation. The kids in Washington interpreted the term to mean jelly beans, with their hard outer shell.

Otherwise, the Beatles were in a celebratory mood, and a good thing, too, because manager Brian Epstein had arranged for them to attend a little after-concert gathering in their honor at the British embassy just outside Georgetown. As a rule, they avoided these kinds of functions. But Epstein had assured them it would be a quiet little party for the overworked staff; an appearance by the Beatles would lift their home pride.

As the car pulled up to the entrance, however, they could tell instantly that they’d been had: women in designer gowns, men in black tie, a diplomatic receiving line, a very la-di-da affair. None of the Beatles was pleased by the situation. An aggressive mob swarmed around them, staring and tut-tutting. It felt as though they were on exhibit, “like something in a zoo,” Ringo observed.

Somehow the boys got roped into announcing the winner of a raffle. They cooperated, albeit reluctantly, but during the exchange a young woman sneaked up behind Ringo and lopped off a hank of his hair with nail scissors. It was the final straw. “What the hell do you think you are doing? ” he growled, furious at the breach of etiquette.

John, who had observed the incident, stormed out of the ballroom, swearing under his breath. The other Beatles followed closely on his heels.

Until now they had always played ball, doing whatever was asked of them, even if it seemed cockamamie or buffoonish. It was part of the game, they figured, good for their careers. But no longer. There was only so much rudeness they would endure. Sure, they were the Beatles; they knew their role. But they wouldn’t play that part again, not with people like that. Not ever.

This is the fifth installment in a series of excerpts from the new TIME book, The Beatles Invasion: The Inside Story of the Two-Week Tour That Rocked America, by Bob Spitz. Copyright 2013, Time Home Entertainment. Available wherever books are sold.