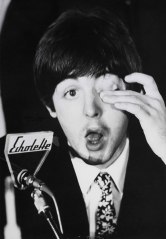

The Beatles during a news conference before their first US concert, two days after their Ed Sullivan appearance.

It was 50 years ago today — Feb. 7, 1964 — that the Beatles took the U.S.A. The four sprightly young Merseysiders landed at New York City’s newly renamed John F. Kennedy Airport (formerly Idlewild) and emerged from Pan Am flight 101 two days before they were to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show. Three thousand fans screamed and, with an urgent group wave toward the Fab Four, effectively buried all previous heartthrob vocalists. Frank Sinatra? A fossil in a tux. Elvis Presley? “He’s old and ugly,” one girl at the airport snorted. (The King had just turned 29 — that’s like 80 in pop-idol years.) A gaggle of fans sang “She Loves You” into the impassive faces of the city’s cops, and some carried signs: “Beatles are Starving the Barbers,” “Beatles Unfair to Bald Men” and, in an early clue to the protest generation, “England Get Out of Ireland.”

Not all those present were unabashed admirers of the new blokes on the block. “It’s phenomenal that people would come to see this and yet they wouldn’t come to see the President,” one young man observed to the Maysles brothers, who were filming a documentary called The Beatles First U.S. Visit, released on DVD with extra footage in 2004. “President Johnson came a few days ago, and there was practically nobody here.” But, as Babe Ruth supposedly said in 1930 when asked why he made more money than President Herbert Hoover: “I had a better year.”

(READ: The Beatles Land at JFK by subscribing to TIME)

Paul McCartney, right, shows his guitar to Ed Sullivan before the Beatles’ live television appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in New York on Feb. 9, 1964.

Actually, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and a landslide election that November, Lyndon Johnson had a pretty good year. But nobody, possibly including Jesus, ever had a better one than John, Paul, George and Ringo enjoyed in 1964. Or a busier one. In the first month they became instant idols in America. In 10 February days they came, were seen and conquered. Later that month they returned to Britain and spent six weeks in London, Surrey and Middlesex shooting a little promo feature called A Hard Day’s Night, which offered a blend of documentary and surrealism, localized comedy and universal appeal that revolutionized film for a while. Their songs monopolized the pop charts for most of the year; one week, the Beatles had the top five songs. And during the dozens of concerts, the hundreds of press conferences, they found time to write some of the perkiest, most vigorous pop around. For starters.

Back then, this was the week that was. The Anglo-Irish quartet had been pop sensations in Britain for the previous year, but now they faced America: world’s most powerful nation, commandant of international pop culture, cauldron of rock ’n’ roll. If they could make it here, they could make it everywhere. And what they made, it soon became clear, was history — musical, cinematic, social and showbizzical. The wonder was that they did it with such blithe, unflappable grace and good humor.

(READ: The Beatles Conquer America in the Feb. 21, 1964, issue of TIME)

This point is pellucid in The Beatles’ First U.S. Visit, a brisk rough sketch of A Hard Day’s Night. Same dashing from train to limo to photo op to TV stage. Same release of tension on a dance-club floor. Same use of wit as the armor against imprisonment and ennui. And the same amazing display of nimble geniality by four blithe Liverpudlians, ages 20 to 24. (The Maysles brothers — Albert on camera and David on sound — showed the same gift for improv; they got the assignment to hang with the lads just two hours before the plane landed.) Leaving their hotel room to go to the Peppermint Lounge, the lads wave a sweet goodbye to the two-man camera crew. Did celebrity ever take such innocent pleasure in its own good fortune? Was the world ever this young?

BEATLE ENNUI, BEATLEPHOBIA

Fresh (or exhausted) off the plane that Friday afternoon, the Beatles faced U.S. reporters, many of whom saw these British invaders and smelled blood. So often in that wild weekend, the questions were rude and ignorant, focusing as they did on the Fab Four’s coiffure. And without fail, the lads replied with witty equanimity. Q. “Are you gonna get a haircut while you’re here?” George (in all seriousness): “I had one yesterday.” Q. “Which do you consider the greatest danger to your careers: nuclear bombs or dandruff?” Ringo: “Bombs. We’ve already got dandruff.” Q: “How many are bald that you have to wear wigs?” Paul: “I am. I’m bald.” John: “Oh, we’re all bald, yeah … And deaf and dumb, too.”

Hair. That’s nearly all the American press knew of the “moptops,” who “look like shaggy Peter Pans, with their mushroom haircuts” (TIME, Nov. 15, 1963) and “sheep-dog bangs” (Newsweek, Nov. 18, 1963). Our cultural custodians didn’t hear much artistry from under the din of their caterwauling acolytes. “Americans might find the Beatles achingly familiar,” TIME opined. “Their songs consist mainly of ‘Yeh!’ screamed to the accompaniment of three guitars and a thunderous drum.” The other newsweekly was every bit as dismissive: “Beatle music is high-pitched, loud beyond reason and stupefyingly repetitive.” One wonders if the writers of these stories had listened to a Beatles record; a couple of singles (“Please Please Me” and “She Loves You”) had already been issued in the States, to tepid response.

(READ: a 1965 TIME story on the hair-story of the Beatles)

As Beatle records were released here and scampered up the charts, the mainstream press still had trouble understanding the group’s appeal and acknowledging the music’s value. Often, Olympian disdain masked simple ignorance. After Jack Paar’s Jan. 3, 1964, show, on which he aired a clip of the boys performing “She Loves You,” Jack Gould wrote in the New York Times that they had “offered a number apparently titled “With a Love Like That, You Know You Should Be Bad’.” (The lyric is, of course, the much more generous “With a love like that, you know you should be glad”; and since the song features the phrase “she loves you” 12 times in just over two minutes, it shouldn’t have been hard to deduce the title.) Gould predicted no duplication of Beatlemania in America: “On this side of the Atlantic it is dated stuff. Hysterical squeals emanating from developing femininity really went out with the payola scandal and Presley’s military service.”

Disinterested grownups weren’t the only ones who rook a while to “get” the Beatles. In September 1963, when “She Loves You” was played on the Rate-a-Record segment of the teen dance party American Bandstand — kids gave a score of from 35 to 98 for a song, which should “have a great beat” and “you could dance to” — it pulled a tepid 73. That’s a D+ where I come from. And when Vee-Jay Records released the group’s first American single, “Please Please Me” b/w “Ask Me Why,” the artists’ name was misspelled as the Beattles.

(READ: TIME readers’ first thoughts on the Beatles)

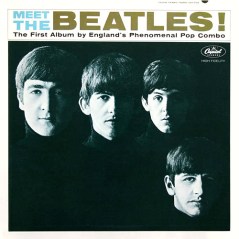

All this is chronicled in a 2004 book called “The Beatles Are Coming! The Birth of Beatlemania in America.” Bruce Spizer, author of three other Beatle books, documents the shortsightedness, missed opportunities and plain dumb decisions that delayed the British invasion by a full year. Capitol Records had a connection with the Brit label EMI-Parlophone that gave it first dibs on the Beatles, but turned down the group four times before finally signing them in November 1963. Capitol then chopped the 14-song British LPs down to 11 cuts for the American releases, thus squeezing an extra album out of the Beatles’ first three. The U.K. LPs for the Beatles films “A Hard Day’s Night” and Help! each featured seven songs from the movie and another six or seven new songs; Capitol released each with the movie songs only and instrumental filler. The company that had first been myopic now graduated to greedy.

THE WHATTLES? — PART ONE

They were smart, funny, good singers, excellent songwriters. And talk about gentlemen: at the end of a song, they bowed deeply, almost to a right angle. Sullivan, calling them “four of the nicest young kids we’ve ever had on our stage,” passed along salutations from Elvis Presley and commendations from the doyen of Broadway composers, Richard Rodgers. The group’s influence was, in every way, salutary. Couldn’t even a grownup tell they were not just the next big thing but The Big Thing?

To appreciate the Beatles, you also may have needed a taste for (not a prejudice against) rock ’n’ roll in its primitive or prime years — the songs of Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins and early Motown, which the Beatles covered in their Cavern period and on their first albums. It helped to know the three-chord structure the Beatles used, then expanded, in their own music. It was the next stop on a road that led from Broadway, Nashville, Memphis and Detroit. But a big stop. Everything before was Kansas, in black-and-white. The Beatles were, musically, a Technicolor Oz.

(READ: The Beatles as Big Business, in the Oct. 2, 1964 issue of TIME)

And if you were a true fan, you had to know where they came from geographically. To a Beatle-lover, Liverpool seemed about the hippest place on earth. Adoptive kid brothers of Lennon and McCartney made pilgrimages to the Cavern, to Brian Epstein’s record store, to the holy homes of the Fab Four. Teenagers from Connecticut studied the accent and vocabulary like the most fervent Berlitz grind, and recited lines from A Hard Day’s Night with the fervor of mimic acolytes. (Repeat, à la George: “She’s a drag, a well-known drag.”)

It was not only the Beatles’ music that inspired this love for all things Liverpudlian. It was the discovery of an English city — working class and influenced by Irish and American adventurers — that had seen it all and was not easily impressed. A thick lilt, a fond parodic cynicism rode the crest of every inflection; a suspicion of all things posh lurked in the slurs and slang. This was the perfect voice to carry pop culture through the mid-’60s, till things went tragic and the Beatles turned into eminences cloistered enough to be their own parodies. But for that luscious moment, the Merseyside moptops were the divine Other: different, hence better. Stateside, we gulped down that Liverpudding.

(READ: Liverpool Rock — “It’s Better Than Beating Up Old Ladies With Bicycle Chains” — from TIME 1964)

The Beatles jump during a photoshoot for their Twist & Shout EP cover.

I remember seeing A Hard Day’s Night at a movie house in suburban Philadelphia during the summer of 1964. I say seeing; hearing was out of the question, due to the shrieks of the band’s bobbysoxer brigade. (The volume level was even higher at a Beatles concert I attended that September. The boys used to say they literally couldn’t hear themselves playing. Well, we couldn’t hear themselves either.) The movie theater, I swear, was informally divided into quadrants, each inhabited by the attendant sisters of one band member: John in the lower left, Paul in the lower right, etc. A closeup of one Beatle would cue an sacred wail from his quadrant.

The girls, consciously nor not, were imitating the film’s climactic sequence, which intercuts shots of the band performing “She Loves You” with reaction shots from the young audience, and returns occasionally to girls mouthing the names of their particular heroes. The unforgettable one is a pretty blond undergoing a kind of anguished ecstasy. She is seen four times: first clutching her hair, then crying into her hand, then sobbing hand to head and finally, at the song’s last break (“You know you shou-ou-ou-ould…”) silently keening a desperate “George.” Over the decades, she’s remained for me the indelible icon of feminine fandom: a girl who is close enough to her idol to realize she will never reach him, and so luxuriates in the sweet misery of a vivid dream, where the harder one runs toward one’s beloved, the farther and faster he recedes.

THE FAB FOUR, AND HOW THEY GREW ON US

What a consuming fever first love is. Americans thought they were in on the initial explosion of Beatlemania. But John and Paul first met on July 6, 1957, and were playing together soon after. By the time the Beatles hit the U.S., their career together was already half over.

On a BBC radio show in 1962 (the group made 52 appearance on the Beeb in three years, and were radio stars before they were record stars), the lads politely introduce themselves: “I’m George, and I play a guitar,” that sort of thing. Then the Beatles’ leader speaks. “I’m John, and I too play a guitar. Sometimes I play the fool.” From the beginning, Lennon was the group’s brain and wit, its Elvis and its Groucho. But unlike Elvis, the early Beatles had the quick, larky humor of kids assured enough to make fun of themselves and everyone else. And unlike the movie Marxes, these were no anarchists — they were many a mother’s daydream of the pop star her daughter might bring home.

(READ: The Beatles on the Beeb)

Except, possibly, for John. From the start he had a spooky, modernist poise. His taut mouth, his appraising eyes made him the group’s soul and wit as surely as McCartney became its prime musical mover. (Shown running down a hotel corridor in the Maysles film, George mimics the mob outside — “Ban the bomb!” — and John ad-libs, “Ban the Pope.”) Cynical, cool, Lennon was the eye of sanity in the Beatlemania hurricane. Asked, during the first U.S. tour, when the Beatles found time to rehearse their songs, he replied, “We wrote ’em; we recorded ’em; we play ’em every day [in their shows]. What do you rehearse? Smilin’ — that’s all we rehearse.” To the art-college student with radical ideas, good nature was not second nature.

John Lennon with Brian Epstein, manager of The Beatles, in England in 1963.

His voice was plaintive but supple; he could sell a pensive ballad (“In My Life,” “I’ll Be Back”) and go orgasmic on “Twist and Shout” (recorded at the end of a day-night in which the group recorded 10 songs; John blew his voice out with the Isley Brothers song, and was spitting blood into his milk). More important, he embodied the group’s snap and sass. TIME magazine’s former International editor and reigning Liverpudlian, Michael Elliottt, O.B.E., told me that if the Feb. 9, 1964, Sullivan show was the defining moment for the Beatles in the U.S., the Royal Variety Performance before the Queen Mother on Nov. 4, 1963, did the same in the U.K.; and it was John who made the famous crack, “Will the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? All the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewelry.” The leader’s edginess suggested a roiling interior life; you could write a novel about what you imagined to be inside John Lennon. And then he had the rock star’s karma to die violently. He was inducted into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist in 1994, five long years before McCartney was.

(READ: TIME’s report on the Beatles’ Royal Variety Performance)

Paul, 20 months younger than John, was treated like the cute kid brother for whom ambition would be unseemly. Certainly, he had ambitions, and certainly he acceded them. He composed the group’s top-selling single (“Hey Jude”), its most widely covered tune (“Yesterday”) and much of its most enduring music. He was the Beatles’ most versatile singer, and not just as a balladeer; attend his scorched-throat renditions of “I’m Down” and “Helter Skelter.” Yet Paul always shivered in John’s shadow. Partly it was his looks. He was cute, coquettish — almost the girl of the group — so how could he be smart? He was the favorite of the screaming females at the early Beatles concerts, but he was not a guy’s guy. No way could he satisfy the male coterie of rock critics. He just tried too hard. Paul wanted to be loved, and that is the essence of the pop star. John didn’t care; that is the essence of the rock star.

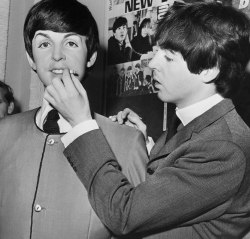

Paul McCartney takes a photo with his wax statue at Tussauds Museum in London.

The odd revelation of The Beatles First U.S. Visit is that Paul, not John, is the comedy star (just as, on the Sullivan appearances, Paul, not John, was the band’s spokesman). In a crowded elevator ride, Paul lightens the mood by announcing, “Ladies and gentlemen, on your right you’ll see the Washington Memorial.” He shows the most interest in the process of filming, as when he tells Al Maysles, “Get the camera down on this mike [held by David], it’d be a big laugh. Go on! Defy convention.” Al finally pans down to the mike, and Paul chirps, “Take 29!” Late that night, when he and Ringo have left the Peppermint Lounge, Paul notices Al behind him and in a posh accent says, “I get the impression you’re filming. Is this true? This man, carrying this lethal weapon on his shoulder… Pretend you can’t see him. He’ll go away.” A moment before, he had bade goodnight to Murray (the K) Kaufman, the WINS DJ who latched (or leeched) onto the group and called himself the fifth Beatle. Paul does some ribbing banter in a tough New York accent, then adds, “No really, seriously, thanks very much.”

(READ: The Beatles Business, 1965)

G.B. ENGLAND. Liverpool. The Beatles first concert at the Empire. 1963.

To the American press, 50 years ago this weekend, Ringo was the Beatle everyone recognized, with the four rings on each hand, the readiest grin and the prominent hooter. (In A Hard Day’s Night, the meddling old man played by Wilfred Brambell tries to stir mischief by saying the other Beatles mock his proboscis: “They’ll pick on a nose.” Ringo replies, “Oh, go pick on your own nose.”) It was Ringo who most easily keyed the American reporters’ notion of the Beatles as a blithe comedy act on the order of the Goons or the Beyond the Fringers — a deep-fried British tradition, though not in rock ’n’ roll. If the Beatles couldn’t persuade U.S. reporters to listen closely to their music, they make ’em laugh at their jokes.

(READ: TIME’s 1964 review of A Hard Day’s Night) — and the Maysles’ Beatles documentary)

Ringo Starr at The Beatles first concert at the Empire, in Liverpool, England, 1963.

But even the lads’ quick wits could cue the itch of suspicion — perhaps we’re all being guyed. In the Maysles documentary, Christopher Porterfield, TIME’s longtime Arts maven, then a cherub-faced 26, is seen chatting with Ringo: “I was going to ask you this yesterday but I thought you might think I was being hostile. I was going to say: Are you kidding us?” For once, a Beatle looks flummoxed by a reporter’s question. Ringo stammers, “We’re not kidding. We just answer how we feel, ya know, what we think.” Chris explained that the lads gave every indication of “enjoying a game that has its aspects of silliness.” And Ringo was saying: the act is not an act. They were four young men who had a good time playing music.

AH YES, THE MUSIC

As Kurt Loder insisted in his TIME 100 essay on the group, the Beatles didn’t emerge from, or atone for, a stagnant caesura in the age of rock. The years between Elvis’ Army service (during which, like a good American, he never went AWOL) and February 1964 overflowed with a sophisticated form of pop-rock, from the Brill Building on Broadway to Brian Wilson’s house in Hawthorne, Cal. At first sound, the Beatles seemed a throwback to the rockabilly ’50s. Their name was a punning riff on Buddy Holly’s band, the Crickets. Harrison’s and Lennon’s thrashing guitars yanked rock ’n’ roll back to its primal instrument after a few years of piano, horns and strings (and it’s stayed that way for a half century). The matching leather outfits of their Cavern days lent them the attitude of rock’s first outlaws. “We looked like four Gene Vincents,” Lennon said, referring to the ’50s rockabilly star, “or tried to.”

In the broad democracy of Top 40 radio of the day, the Beatles rubbed sounds with Martha and the Vandellas, Steve and Eydie. They’d borrow, then improve; scavenging gave way to alchemy. It was always a fight to be the best. “We’d try to beat what we were doing,” Paul said. The Beatles beat everybody — which is why, when the mania faded and the old scandals raise a yawn, the music lives.

(READ: The Beatles — finally — make the cover of TIME, May 21, 1965)

Believers in the sanctity of the single, the Beatles made classics in miniature. A melody simple enough to leech onto the brain and fresh enough to bear repeated airplay. The bending of a cliché, musical or verbal. High harmonies so close that John, Paul and George could be Siamese triplets. In and out in no time. Two minutes, two and a half tops — leave ’em wanting to hear it again. And to hear others just as good. That’s how the Beatles created the pop album. Before them, an album was a couple of hits and 10 cuts of filler. With the Beatles, every album was an event.

This inventiveness was evident from their earlier songs, and from the first moments of each song. They often dispensed with the standard four-bar instrumental intro. Five rapid base-drum beats (“She Loves You”); or a single, startling guitar chord (“A Hard Day’s Night”) or door-slamming rim shot (“Any Time at All”); sometimes just the voice, attacking without warning on an uptempo number (“All My Loving,” “Can’t Buy Me Love”) or a ballad (“P.S. I Love You,” “If I Fell,” “No Reply”) — announced that they couldn’t wait to get to the song, and didn’t want disc jockeys chattering over their lead-ins. Lotta content, little filler.

(READ: TIME’s review of the Beatles’ second film, Help!)

The closings were a switch, too: not so many fade-outs, which had become the rule in Brill Building and Phil Spector pop. The Beatles, who played in clubs long before they released their first single, knew that songs with a climax, a point, a socko finish, were guaranteed audience-goosers. Listeners cheered as “She Loves You” soared into its final yeah-yeah-yeahs, with the last chord a minor-key sixth — daringly dangling.

And in between was the song. The typical verse and chorus of a Beatle tune from 1963 and ’64 was beguiling enough — usually some variation on a 12-bar blues (“A Hard Day’s Night”) or the C-A minor-F-G ballad format (“Do You Want to Know a Secret”) — but it was in the bridge, or middle section, that Lennon and McCartney first raised the bar for pop-rock songwriting. They explored new chord patterns, prettier melodies in so many bridges (where to start?) from “I Want to Hold your Hand,” “It Won’t Be Long,” “Any Time at All,” “Things We Said Today,” “A Hard Day’s Night,” “I Feel Fine” (where to stop?). “I’ll Be Back” has two plaintive bridges, expressing two shades of unease, each running a half-measure longer than expected, without jarring the ear. It sounded fresh and natural; the strain never showed.

THE WHATTLES? — PART II

Ten years ago, I showed the clip of Chris Porterfield and Ringo Starr to a young TIME staffer. He correctly guessed that the young reporter had aged, ever so gracefully, into Chris, then asked, “But who’s the other guy?”

It’s not fair to either of us. The young staffer shouldn’t be expected to recognize the drummer from a group that had an eight-year recording career that ended 44 years ago; and I shouldn’t have to know that he doesn’t know. Chris might be chagrined if I couldn’t distinguish among Patty, Maxene and LaVerne (the Andrews Sisters) or, in opera, John, Charles and Thomas. Most young people today are as fuzzy on Beatle IDs as reporters were that February ’64 weekend. (“Which one are you?” “I’m Paul.”) The difference is that, 50 years ago, it mattered.

(READ: Harold Bronson on How the Beatles Changed Rock ‘n Roll)

I’ll bet most people in their twenties can tell Mick Jagger from Keith Richard. That’s partly because the Rolling Stones have kept performing into their sixties — the Open Coffin Tour hits the road every few years. But mostly because, in lingering musical influence, the Stones are it. The Beatles are out.

I remember seeing the Stones in the American TV debut, in March 1964, on an ABC variety show, The Hollywood Palace. They were to sing two songs. But Dean Martin, the host, lavished so much air time on insulting the quintet — introducing a trampolinist, he gibed, “That’s the father of the Rolling Stones. He’s been trying to kill himself ever since” — that the Stones never got to do their second number.

(READ: Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Stones film Shine a Light)

Having defied conventions, the Beatles had quickly become their own convention: uniform clothes and haircuts, light banter, sweet songs, no leering or posturing. The Stones broke those rules, and wrote new ones that have held ever since: a blues-based musical scheme, a strutting, sexually aggressive lead singer, the exaltation of rhythm over melody, of energy over craft. If those early Beatles were perceived as endearing, the Stones were seen as dangerous. The lure of the lurid would lead pop-rock away from the Liverpudlians and into the grip of the Londoners. Everyone stopped smiling and started glowering. Rock became an expression not of joy but of pain and anger.

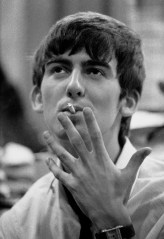

In the 10-part 1996 documentary Anthology, George tells how bored the Beatles became with concerts; sometimes they’d run through their 30-minute set in 25, by playing every song faster. For the audience, the concert experience was wholly votive — unintelligible and incandescent, like Mass in Latin. But the band no longer wanted to do it on the road. They stopped touring in 1966 and holed up in a recording studio with their maestro and enabler, George Martin, to make pop songs art songs.

(READ: The Beatles Reunion in Anthology, 1995)

Meanwhile, and ever since, the Stones perfected the rock act as traveling circus, high-wire act and freak show. That was another crucial component of late-century rock: a live, spontaneous feel rather than the perfectionist, studio sound of the Beatles. Playing huge stadiums meant performing the assaultive, theatrical music that would fill and rock those stadiums. That practically killed ballads, which were nearly half the Beatles repertoire. Lennon and McCartney, pushing the limits of pop songwriting, have little to do with today’s rock, which pushes the limits of content but is musically conservative. And the pure vocal harmony of John, Paul and George — that’s fun. (the band), or for wimps.

Musical fecundity, vocal virtuosity, a shapely melody — these may be antique standards. But I’ll apply them, here, and say that the Beatles achieved something nobody else in pop music did: they made each album of higher quality than the one before (if you acknowledge that Let It Be was the chronological predecessor to their eloquent farewell, Abbey Road). Their lives inevitably became more complex, but their music retains a lustrous purity and verve. Though it’s a shame that nobody wants to be the Beatles any more … well the Beatles did, and that’s enough. They made music, and its listeners, feel good. And that’s still true today, 50 years on.

To anyone who was around when Beatlemania erupted in the U.S., it seems like yesterday.

To read more about the 50th anniversary of the Beatles’ first visit to America, check out the new TIME book, The Beatles Invasion: The Inside Story of the Two-Week Tour That Rocked America, by Bob Spitz. Available wherever books are sold.