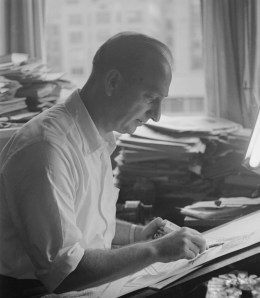

Cartoonist Herbert Block at work.

Herbert L. Block belongs on the short list of the greatest journalists of the 20th century, even though rarely wrote more than a few words at a time and worked in a cluttered office far from distant battlefields. Almost singlehanded, he rescued the craft of editorial cartooning from a fen of mediocrity, then turned his sharp pen on the most important issues of his long lifetime, from tyranny to human rights.

Known by his signature, “Herblock,” this longtime fixture of The Washington Post editorial pages was richly honored during his lifetime. Herblock won three Pulitzer Prizes, shared a fourth, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and saw his work collected by the National Gallery of Art.

His influence could be counted in the number of presidents who cringed each morning at what they might find in their morning paper. From Herbert Hoover to George W. Bush, the pain of a well-aimed Herblock dart was a sensation shared by more than a dozen chief executives. One of them, Richard Nixon, counted the cartoonist among his most dangerous nemeses.

He was also stunningly well-compensated. His tenure at The Post went back to the days when the paper was a near-bankrupt concern, and at least once he was presented with the dodgy opportunity to trade some paychecks for company stock. The paper’s rise to national prominence was inseparable from Herblock’s widely syndicated work. When publisher Philip L. Graham made the cover of TIME in 1956, the background to his portrait was a collage of the cartoonist’s instantly recognizable images. By the time Herblock died in 2001, his original Post shares had split 240-to-1 and each resulting share was trading above $500. The ink-stained wretch left an estate valued at $90 million.

But somehow Herblock’s fame a dozen years later doesn’t quite measure up to those outsize standards. He lacked the self-promotional or social-climbing energy of many other Washington legends, and the star-making power of radio and television eluded this balding fellow with the huge nose and the voice borrowed from Disney’s Goofy.

Herblock lacked the glamor of Edward R. Murrow—although he beat Murrow to the job of unmasking the demagogue Joe McCarthy by a good four years. He lacked the Hollywood pizzazz of his younger Post colleagues Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—although his Watergate cartoons pointed the finger at Nixon long before the scrappy reporters connected the dots. He lacked the reverential cult of New York Times columnist James “Scotty” Reston—even though Herblock was immune to the head-spinning half-truths of high-powered dinner companions who sometimes managed to snow the sage. Herblock preferred dinner in front of the TV, which he tuned to The Yogi Bear Show and Rocky & Bullwinkle.

HBO Documentary Films now steps in to remedy the imbalance a bit. Beginning on Monday, Jan. 27, HBO will air a feature-length biography, Herblock: The Black & The White, directed by Michael Stevens, whose Thurgood Marshall biopic also aired on HBO. A longtime fixture of Herblock’s Washington, Academy Award winner George Stevens Jr., produced the film.

WATCH: HBO’s trailer for Herblock: The Black & The White

Featuring expert testimonials from fellow cartoonist Jules Feiffer, Daily Show host Jon Stewart, the aforementioned Woodward and Bernstein and many others, Herblock is proof of the stirring power of truth served up boldly and sweetened with wit. At the same time, the film is never as compelling as the work itself—perhaps unavoidable, because the work sprang from an invisible space between the artist’s ears. And even when it lands, as veteran broadcaster Tom Brokaw says, “like a punch in the face,” the humor quotient of a great cartoon has a way of undercutting the drama.

Put another way, the two things that make a great editorial cartoon—the clarity of the idea, and the wit of the execution—originate in the black box of the mind, and thus defy dramatization. Herblock’s greatness was foremost as a thinker, an analyst who saw to the heart of things when others were distracted by surfaces. For example, when many of his fellow liberals were inclined in the 1930s to make apologies for the Soviet leader Stalin because they had a common enemy in the fascist Hitler, Herblock correctly portrayed the two dictators as equivalent faces of the same murderous totalitarism. Later, he recognized the nuclear arms race was a monster that linked, rather than divided, the Cold War rivals Kennedy and Khrushchev. His portrayal of Vietnam as a prison for Lyndon B. Johnson came when even Johnson himself was only beginning to awaken to the bitter reality of that metaphor. For this ability to find the essence of noisy controversies, at his death I called him “the Orwell of the drawing board,” and more than a dozen years of reflection has done nothing to change that assessment.

A filmmaker tackling Herblock’s work has no expeditions to foreign foxholes to work with, no late-night meetings with shadowy sources, no investigative journeys to bad parts of town, or confrontations with colorful wiseguys. Stevens tries on a variety of techniques to answer this challenge. He has an actor portray the cartoonist in his office packed with coffee cans full of pens and pencils. In speeches based on Herblock’s memoirs, he explains himself to an unseen interviewer. Other actors offer scenes from Block’s boyhood—these are the weakest moments of the film, but they don’t last long. The meat of the material is presented Ken Burns-style, with talking heads interspersed among zooming, panning, images of mostly static photos and cartoons.

Herblock is an earnest, well-made accounting of a remarkable and important life. It’s fascinating to hear such an authority as Feiffer credit him with the “rebirth of the editorial cartoon as an instrument of power” long after the deaths of the pioneers Daumier and Nast. To a generation that sniffed at Herblock’s outdated sketches of men in fedoras housewives in pearls—favoring the suppler work of such younger artists as Pat Oliphant, Jeff McNelly and Garry Trudeau—it’s arresting to hear Bob Mankoff, cartoon czar of the New Yorker, praise Herblock as “a prodigy” of “the graphic line.”

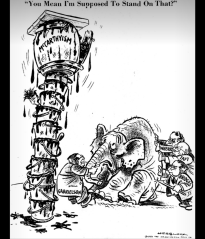

I wish a few more of his best cartoons had been allowed to land in full, as they did in each day’s paper, rather than emerging slowly under the eye of a moving camera. I felt this especially in the case of my favorite Herblock—and arguably his most influential cartoon. It ran on March 29, 1950, and showed a team of Republican leaders dragging and prodding a reluctant GOP elephant toward a tottering tower of leaky tarbuckets labeled “McCarthyism.” The Wisconsin senator was just getting started with his reckless charges of vast communist conspiracies inside the U.S. government. This cartoon coined the term that would become a standard part of the American political lexicon. The elephant’s expression is sheer, hilarious genius, and the caption—“I’m supposed to stand on that?”—is a masterpiece of scalpel work, cutting to the heart of a complex idea in six little words.

We need to see it all in one glimpse to get the full impact, because the essence of the editorial cartoon—the essence of daily newspaper work generally—is that it works quickly and clearly or not at all. As longtime Post columnist Richard Cohen says in the film: “To tell a story and to capture political complexity in a couple of line drawings is amazingly difficult.” Comedian and satirist Lewis Black adds, “His succinctness makes what we do on The Daily Show kind of silly.”

Watch the film. With luck it will lead you to surf the internet for the cartoons themselves. (Start here and here.)

And from there, dig deeper into the actual history of Herblock’s vast era. Because the more we know and understand about those times, the greater his journalism becomes.