Broadway musicals have for years looked to the movies for inspiration, but lately the film-to-stage conveyer belt seems to be running in overdrive. Remember The Wedding Singer, Sweet Smell of Success, Leap of Faith? Neither does anybody else — though they all had brief Broadway runs in the last few seasons. This season we’ve already been served up Big Fish, based on the Tim Burton film, and soon to come are musical versions of The Bridges of Madison County, Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway and even Rocky. Somewhere in the wings, Diner is looming.

They aren’t all duds. Kinky Boots, last year’s Tony-winning musical based on a 2005 British film, was far from my favorite show, but on its own shamelessly crowd-pandering terms, it worked on the stage. More commonly, however, these shows measure up neither as good adaptations nor good musicals.

The latest example: Little Miss Sunshine, an amiable but unsatisfying musical that just opened off-Broadway after being developed at California’s La Jolla Playhouse. Based on the hit 2006 comedy (winner of two Oscars), it follows a financially-strapped Albuquerque family making a road trip to Redondo Beach, California, so that their youngest daughter can compete in a Little Miss Sunshine talent competition.

A story that takes place largely on the highway, inside a cramped Volkswagen bus, might not seem the most promising material for the stage. But director James Lapine and choreographer Michele Lynch have managed it inventively, putting the actors in castered chairs and keeping them moving around the stage in unison. And the intricate, lightly orchestrated score by the talented William Finn (Falsettos, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee) is tuneful and nicely matched to the characters.

What the musical can’t really match is the depressive quirkiness of the dysfunctional family in the movie. The foul-mouthed grandfather (Alan Arkin won an Oscar for the role) is played by David Rasche, a good comic actor who seems both too young and too sensible for the part. Uncle Frank (Rory O’Malley), a gay college teacher who has just tried to commit suicide, doesn’t look like he’s had a depressed day in his life, while Dad (Will Swenson), an aspiring self-help author, seems less like a failed dreamer than a drab nonentity.

That leaves us with Hannah Nordberg as little Olive — cute and well-coached, but only that —and her big moment in the talent show, where the family barge onstage to rescue her, in a climactic, feel-good bonding experience that seems even more contrived and manipulative than it did in the movie. Sunshine has its bright spots, but as a stage musical, it’s mostly cloudy.

(Little Miss Sunshine, Second Stage Theatre)

.

Yet, just as I was about to give up on musicals and go see a movie, along comes A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder. Just arrived on Broadway after runs at the Hartford Stage and San Diego’s Old Globe Theater, this enjoyable, well-polished show is based on the 1949 British comedy Kind Hearts and Coronets, about an English gentleman who murders each of the eight relatives ahead of him in line to inherit a family title and fortune — famous for Alec Guinness’s performance as every one of the family members who get bumped off.

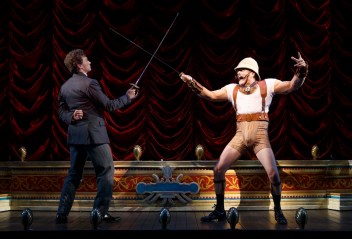

The material translates much more comfortably to the stage: instead of neurotic family interactions, we get an action-filled black comedy, broad satire of upper-class British manners — and a tour-de-force actor’s turn. Jefferson Mays, a Tony winner for his multiple-role one-man show I Am My Own Wife, does the quick-change duty here, and he’s spot on, without too much showboating, as a string of stock Edwardian twits — a stuffy banker; a dotty clergyman; a big-busted, globe-trotting philanthropist. It’s a made-to-order Tony performance, but just as indispensible is the charming, wide-eyed, curly-haired Bryce Pinkham, who really holds the show together as the homicidal heir.

Director Darko Tresnjak has a lot of fun with his inventive, low-tech staging of the murders — a plunge down a clock tower, a fall through the ice, a beekeeper swarmed by his own bees. Robert L. Freedman’s lyrics can be a little twee and on-the-nose — “I Don’t Understand the Poor,” or the mock-homoerotic number, “It’s Better With a Man” —but Steven Lutvak’s operetta-like score is bright and winning.

My only reservation is a certain anodyne frivolousness of the whole enterprise. The opening chorus number warns us, jokingly, that we’re about to see a show about revenge and retribution — “So if you’re smart / Before we start / You best depart.” That pronouncement can only come from a show that knows it’s going to offend absolutely nobody. Not even those who loved the movie.

(A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, Walter Kerr Theatre)