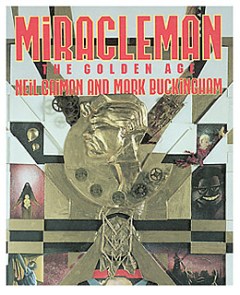

That Marvel Comics has finally given an official launch date its much-delayed re-release of Miracleman — the 1980s superhero series written by Alan Moore, until he was succeeded by Neil Gaiman — is news likely to thrill both hardcore superhero fans and occasional visitors to the genre. (Moore will be credited as “The Original Writer” in the re-release.)

Known today for being a long-out-of-circulation gem, Miracleman was a comic that spawned countless imitators, including, one could easily argue, Marvel’s own The Ultimates — a series that heavily influenced Marvel’s “Cinematic Universe.” And it represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and followed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on “realism” in superhero comics — something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.

(WATCH: Understanding the Marvel Cinematic Universe)

Miracleman arrived in 1982, in the pages of independently-published comics anthology Warrior (Originally titled Marvelman, the name change came years later upon threat of legal action by Marvel Comics, ironically enough), Moore’s attempt to address a handful of traditional superhero tropes — magic words that transform regular guys into beings of supreme power, mad scientists, epic battles between hero and villain — in a fashion more in tune with his own desires and the notion of an adult audience.Scheduled to begin in January 2014, the reissued Miracleman appears after recent re-releases of two other equally important, if lesser-known, works of 1980s superhero deconstruction: Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s Zenith, and Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy’s Paradax. Taken together, the three series offer a time capsule of just where the superhero genre was thirty years ago — and perhaps a sense of sadly missed opportunities, as well.

Those genre conventions weren’t treated as parody — Miracleman is, if nothing else, an amazingly reverential book to superhero convention — but instead pushed towards a stylized “realism” as Moore and various artistic collaborators including Garry Leach, Alan Davis and his Swamp Thing partner, John Totelben struggled to mine drama fit for grown-ups out of children’s characters.

Paradax, which struggled through an even-more publishing irregular schedule than Miracleman — first appearing in the anthology series Strange Days in 1984, then graduating in 1987 to a short-lived series that lasted only two issues, one of which was made up of reprints of the earlier material — also attempted to make superheroes suitable for adults, but went in entirely the opposite direction to Moore’s efforts.

Paradax‘s cast was realistic in ways in which Miracleman never managed, in large part because they were too aimless, ill-tempered and lazy to jump through whatever plot hoops Moore had created to echo the comics of his youth. Instead, Paradax grafted the visual iconography and inventive, shameless energy of the so-called “Silver Age” onto characters acting like you or I, creating a colorful, chaotic alternative to the graceful seriousness Moore offered.

The two differing approaches eventually collided in Zenith, which made its first appearance in long-running British anthology 2000AD during 1987 (By which time Paradax had been and gone, Miracleman was midway through its run, and even Moore’s better-known Watchmen had started publication). Taking the grounded nature of Miracleman and grafting on the (studied) disinterest and willingness to embrace the ridiculous from Paradax, Zenith — the series that made writer Grant Morrison’s name, paving the way for more famous work like The Invisibles, Animal Man or All-Star Superman — is, in many ways the best of both worlds: less heavy and pretentious than Moore et al’s efforts, but more coherent and consistent than Milligan and McCarthy’s playtime.

All three series demonstrated a new generation of creators struggling to update the superhero genre for an audience who, like them, had grown up with the material, with each taking a different approach towards achieving that goal (Gaiman’s work on Miracleman, inherited after he had already started his Sandman series for DC Comics, feels disconnected from this if only because, by the time Moore left the series, he had essentially taken the series past the superhero genre altogether, into something else, something less easily defined). The visibility of Moore’s work on Miracleman and Watchmen easily eclipsed both Paradax and Zenith, but also seemed to offer a more easily recognizable template for others to follow: Make everything more violent, more painful.

That led to years of stories with superheroic rape, brainwashing and murder — grimness that made the genre seem more ridiculously adolescent than anything, something Moore himself has complained about since. If nothing else, the re-release of Miracleman will hopefully allow readers to see the humor and kindness in that series for themselves, just as the reissues of Zenith (in Rebellion’s The Complete Zenith) and Paradax (in The Best of Milligan and McCarthy) point to different directions still open for exploration, now that everyone is watching to see where superheroes go next. Just imagine.