The often-quoted adage that history is written by the winners, while generally true, only tells part of the story when it comes to wars large and small. Not even victors, after all, can claim dominion over every piece of information about a conflict; the aftermath of any war contains mysteries that can, at times, feel impregnable.

Of course, for survivors of those who never make it home — whether comrades, spouses, children or simply friends — the most harrowing of these mysteries is what became of those who went missing. As of this writing, for example, more than 73,000 U.S. troops are still unaccounted for from the Second World War — a number that represents more than all the U.S. deaths in Vietnam; more than twice as many Americans as were killed in Korea. Picture a large American town emptied of every one of its citizens — and the countless number of those left behind who must go on without knowing what became of loved ones, yet morally certain that their husband, father, brother or pal met a violent death, alone, somewhere far from home.

(MORE: The Liberator: A User’s Guide to Hell)

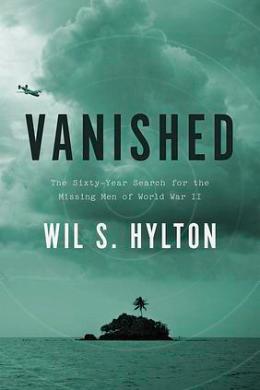

In his deeply textured, propulsive new book, Vanished: The Sixty-Year Search for the Missing Men of World War II, journalist Wil Hylton digs deep into one of these fraught, abiding mysteries — the fate of the crew of an American B-24 bomber that crashed in the Pacific in the fall of 1944 — and emerges not with definitive answers to all of his questions, but with a galvanizing tale of sacrifice, loyalty and, perhaps above all, tenacity. It spoils absolutely nothing to disclose, at the outset, that there are no happy endings here. But in a narrative that veers expertly from the tension and tone of an old-school mystery to the informed, straightforward lexicon of history, Hylton has fashioned something far more enduring than a feel-good read: he has illuminated the depths of pain war can visit upon distant generations, while paying tribute to a central tenet of the Soldier’s Creed: never leave the fallen behind.

Disclosure: One of my brothers is thanked in the acknowledgments, having provided Hylton with research material in the form of documents and books that our father, a WWII vet, brought back from the Pacific. Our dad flew more than two dozen missions in the Pacific as a gunner on a B-24 in the 307th Bombardment Group — the same bomber group featured in Vanished.

(MORE: It Sucked to Go Through World War II. Inferno Will Remind You Why)

With any mystery — more so than with many other sorts of tales, whether fiction or nonfiction — plotting and characterization carry equally critical weight, and in Vanished both elements are well-served by Hylton’s approach to what could have been a numbingly convoluted story. Bouncing from character to character and from era to era — from the modern-day researchers and obsessives who crisscross the globe searching for downed planes and missing troops to the dozen men who flew in the B-24 around which Vanished revolves — Hylton keeps a complex narrative firmly on track while deftly leading up to the final “reveal” of what really happened to the bomber’s crew.

We meet remarkable people like Pat Scannon, a physician with a PhD in chemistry who, after a scuba-diving trip to Palau in the western Pacific in the early 1990s, becomes obsessed with unraveling the riddle of lost WWII airmen; Tommy Doyle, who has grown up with two very different versions of what happened to his dad, Jimmie, who shipped out when Tommy was fifteen months old, and never came back; and Jack Arnett, the temperamental, domineering and highly skilled pilot of the lost B-24 who, until that doomed flight in ’44, had never flown with the crew who would share his fate. Hylton weaves the stories of these and literally scores of other men and women together, their voices arching over and under one another, echoing back and forth across decades, until the entire saga comes together as a coherent and, at times, deeply moving whole.

Beyond the technical strength of Hylton’s achievement, meanwhile — beyond the obviously informed and determinedly reported history one encounters in the book — there are passages so expressive that we’re constantly reminded we’re in the hands of a phenomenal writer, and not a mere correspondent.

(WATCH: War Veterans Talks to TIME About the Shutdown)

“On a clear day,” Hylton writes of the Pacific island group called Micronesia, “the islands appeared to sprinkle the water like a thousand emeralds on a plate of blue glass, each one glittering and distinct in the brilliant tropical sun, but from the sky you could see that it was an illusion: the islands were not islands at all. Beneath the surface, they were all fused together into a single underwater mesa, which rose ten thousand feet from the seafloor and leveled off just below the waterline. What seemed to be, from ship or shore, hundreds of individual islands were really just the slight hills and rises on the mesa top, bumps that rose a fraction too high and breached the open air. . . . “

That a region of such transcendent beauty was the site of some of the 20th-century’s most savage and prolonged warfare is just one of the many unsettling paradoxes suggested by Hylton’s book. But perhaps the greatest paradox resides in the triumph that the book both records and embodies: namely, that history is never really over, as long as there are those willing to fight to keep the memory of loved ones alive — no matter how long ago those loved ones might have perished.