I spent time with Stanley Kauffmann only once, in December 1971, at a Modern Language Association seminar in Chicago. He, the distinguished film critic of The New Republic since 1958, and I, a pup who edited Film Comment magazine and wrote freelance for The Village Voice, appeared on a panel about, I think, movie screenwriting. That afternoon we sat together on a flight back to New York City, and he was most generous in chatting with someone who was born the year Stanley wrote a play, Bobino, in which Marlon Brando made his professional acting debut.

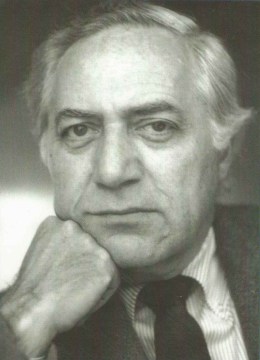

What I remember most acutely from that couple of hours on the flight is Stanley’s august presence. An actor in his youth, he spoke in elegant modulations and carried himself regally. His wavy gray hair and the upward jut of his chin gave him a movie-Presidential bearing, George Washington merging into FDR. His reputation was even loftier, as a careful writer who spoke his mind with a tart elegance but didn’t take sides in the disputes then raging between Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris and their critical coteries. Stanley was above all that; he plied his craft in solitary Olympian grandeur. As we flew through the clouds, he might as well have gestured out the window and said, “This is where I live.”

Stanley Kauffmann died today in Manhattan, at 97, after a bout of pneumonia. As imposing as his long life was the length and breadth of his career. Unlike most film critics of the last 40 years, whose prime salaries came from daily or weekly journalism, Stanley had an actual life before and beyond movies. He was an actor, a prolific playwright, a stage manager, a novelist, an editor at Knopf, Ballantine and Bantam Books (where he discovered and published Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer) and later a teacher — always a teacher, in prose and in person. He called on his diverse CV to lend erudition and life knowledge to his reviews in The New Republic, where his 55-year tenure must set a record for the mutual loyalty of a critic and his magazine. (Recently Kauffmann was writing for The New Republic online only; the job on the print side was inherited by another relative pup, David Thomson, 72.)

In the introduction to the 1972 anthology American Film Criticism: From the Beginnings to ‘Citizen Kane’, which he edited with Bruce Henstell, Kauffmann wrote about the lightning-bolt impact of the moment he “discovered film criticism.” In 1933, as a student at NYU, “I picked up a copy of The Nation and read a review by William Troy — I can’t recall the title of the film — in which he compared a sequence in a new picture with a similar sequence in a previous one to show relations of style. I’m not sure that my jaw actually dropped, but that’s the feeling I remember.” Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus had no more electrifying revelation.

It’s important that this genial shock came from reading an analysis of film form, not from political or social content. Kauffmann’s liberal views mirrored those of his magazine (except when it went slightly neo-con for a while), but his reviews often examined the visual primacy of a medium too often mistaken for filmed literature. Whatever the voltage of that Troy review, Kauffmann spent a quarter-century in other pursuits before combining his cinephilia with his respect for film criticism.

Within a decade, in the late 1960s, film criticism exploded into a popular performance art. The front page of The New York Times Book Review carried dispatches in the ferocious cage matches involving Kael, Sarris and John Simon, which for a season or two made movie critics cultural celebrities nearly as famous as the stars whose films they reviewed. Kael, at The New Yorker, wrote like a brilliant bag lady busting into the drowsy Masonic lodge of respectable critics. Sarris, at The Voice, somehow combined epigrammatic wit with a fan’s delirium. And Simon, at The New Leader, spat and shat on them both, defending his notion of high culture in a tone of Transylvania hauteur. Kauffmann, though, stoutly resisted the declamatory; he kept his voice in the key of murmur. His role was that of the arbiter who would see a film, gauge the convulsive reactions of others and rule: No, not quite.

(READ: Corliss’s tribute to Andrew Sarris)

The extremes of other critics made his moderation seem salutary. Noting the critical acclaim for Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita on its American release in 1961, Kauffmann called it “an ineffectual Sodom, made more remote by its orgies.” Like a fellow who had seen, and finally tired of, his share of bacchanalia, he tutted: “Fellini has set out to move us with the depravity of contemporary life and has chosen what seems to me a poor method: cataloguing sins. Very soon we find ourselves thinking: Is that all? We feel a little like the old priest in the story who is bored not only by the same old sins in the confessional but by the necessity to appear shocked so as not to offend the sinner.”

Kauffmann often felt obliged to pour cold water on the hot loins of critical exuberance. In 1968 the New York Film Festival showed a restored version of Max Ophuls’ 1955 Lola Montes, which Sarris had anointed as “the greatest film of all time.” Kauffmann agreed that “There is not a flaw in the mise en scène, not a dull frame for the eye. … But after it’s all over — before then — we are faced with the Chesterton comment. The first time G. K. Chesterton walked down Broadway at night past the flashing electric advertisements, he said, ‘What a wonderful experience this must be for someone who can’t read.’ In the case of Lola, one might add: or for those who want to pretend they can’t — figuratively — read.” Here is a smackdown of almost Alexandrine virtuosity. (But Sarris was closer to being right on this than Kauffmann was.)

The view from the high bench was just as severe in 1994, when Quentin Tarantino was the new Fellini. “What’s most bothersome about Pulp Fiction,” Stanley wrote, “is its success. This is not to be mean-spirited about Tarantino himself; may he harvest all the available millions. But the way that this picture has been so widely ravened up and drooled over verges on the disgusting. Pulp Fiction nourishes, abets, cultural slumming.”

Not that Kauffmann couldn’t be amused, enthused, by an auteur’s stylistic excesses. In 1969 he found “something touching and maniacal” about Sergio Leone’s grand-opera horse opera Once Upon a Time in the West: “The whole huge panorama is seen through foreign eyes. No matter what time of day it’s supposed to be in a scene—morning, noon, or dusk—the light is Mediterranean gold. Tonino Delli Colli, the cinematographer, has covered everything with melted parmigiana. Every setting, no matter how stark it is supposed to be, finds a way to be ornately stark. … The score by Ennio Morricone suggests how Puccini would have written his Western, La Fanciulla del West, if he had done it about 1935. Broad lyric themes, right out of La Scala, accompany violent gunplay and dusty confrontations. This Western has the first shootout in which I expected the duellists to burst into bel canto.”

Kauffmann assumed his New Republic post when Hollywood pictures were considered infra dig and virtually all serious criticism was devoted to foreign-language films. (Kauffmann was especially illuminating on the films of the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu.) Those would also be the movies patronized by his readers and many others; in the 1960s foreign films accounted for fully five percent of movie tickets sold in the U.S.. Now that percentage is minuscule, perhaps a tenth of what it was; and even the most intellectual critics spend most of their space on mainstream and Sundance-indie product. Perhaps alone among his younger peers, Kauffmann has kept the foreign-film faith. (Stuart Klawans of The Nation might place second.) Check a representative sample of Kauffmann’s work on Rotten Tomatoes to see how he also maintained the high standard of critical acuity and compositional vigor. Filing until a month or two before his death, The Old Master never wore out.

Occasionally his recent reviews contained glimpses of autobiography. This summer, reviewing the bee documentary More Than Honey, he summoned an image from 80 years past: “When I was a schoolboy, they showed us two such documentaries — I don’t know why — and I was very keen about them.” At the end he wrote, “I left [the film] with the feeling that I may have felt harbingers of when I was a boy. I am a member of a race that is kept in being by the support of flying insects who sip on flowers to live.”

Stanley’s review of Amour, Michael Haneke’s portrait of an old married couple facing degeneration and death, must surely have been informed by his 59-year marriage to Laura Cohen, who died shortly before he saw the movie: “What they [the husband and wife] both know, what is being marked, is the filling of their home with inevitability. Without explicit comment they know the approach of her end, to be followed not long after by his, this double slipping away in the place where they lived so fully.” Ever the Ozu admirer, he added: “I haven’t seen meals involving older people that affected me so keenly since Ozu’s Tokyo Story.”

The man who reviewed Alain Resnais’ first feature, the 1959 Hiroshima, Mon Amour, was still around this year to cover You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet, which the great French director said was his last. “We are left at last more with gratitude to Resnais and his career,” wrote the 96-year-old of the 91-year-old, “than actually being as moved as we are meant to be by this film.” And here I have to say that Kauffmann’s peccadillo, which he shared with Kael, was his overuse of the dictatorial “we” to bring the reader in line with his own view. (Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge!: “Nothing in the film moves us.” Rafi Pitts’ The Hunter: “It holds us…” Aki Kaurismaki’s Le Havre: “We are so held…” And the Resnais film: “What affects us most…”) As Tonto might say, “What you mean ‘we,’ Kauff Mann?”

But we are left with gratitude for Stanley and his career, and for his persistent — and what must have been, in his mid-nineties, heroic — fealty to the twin muses of movies and movie criticism. In 1980, introducing his collection Between My Eyes, “Nothing quite revitalizes hope like seeing a good film. The making of a good film is an action that seems to contradict reason and circumstance, yet it keeps happening.” I’ll warrant that his hope remained vital until his death.

One of his last reviews, posted this Aug. 2, was of Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours, the tale of two strangers who meet in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Art Museum. Kauffmann’s description of the filmmaker might also be the reviewer’s self-portrait: “It’s as if Cohen had lived for centuries among these places, and sometimes with art that encapsulates these centuries, and is pleasantly imprisoned within its strength.”

Farewell, Stanley Kauffmann, our pleasantly enlightening prisoner of film. Have a safe flight home.