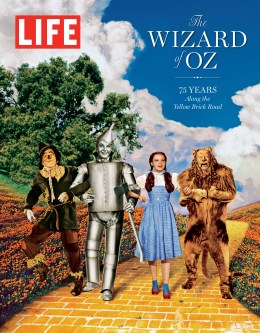

This is the final entry in a five-part series, adapted from an essay in LIFE’s The Wizard of Oz: 75 Years Along the Yellow Brick Road, published by Time Home Entertainment and available on newsstands this week.

Dorothy Gale dropped into Oz and achieved it all: legendary warrior, national heroine, Empress for life. What else could she want? She says she wants Kansas — that monochromatic land where no one showers love on her, and a mean lady took Toto away to be killed.

To justify her decision to return from the Emerald City to the Gale farm, the screenwriters of The Wizard of Oz attempted an impossible headstand and fell flat on their prats. In Dorothy’s big speech about the lesson she’s learned, she tells Glinda: “If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look any further than my own back yard. Because if it isn’t there, I never really lost it to begin with.”

What in the world does this mean? Back in Kansas, Dorothy had boldly expressed her “heart’s desire” — in her “own back yard.” Indeed, she sang it: “Somewhere over the rainbow, / Way up high, / There’s a land that I heard of / Once in a lullaby. / Somewhere over the rainbow, / Skies are blue. / And the dreams that you dare to dream / Really do come true.” She wished upon a star and woke up where the clouds of a lonely girl’s Kansas life were far behind her. She dreamed Oz, or went there, as an expression of that innocent desire.

And yet, at the end of her adventure and the apogee of her acclaim, Dorothy clicks her heels, summons the words of John Howard Payne’s lyric for the 1823 song: “There’s no place like home.” She awakens in bed, with Auntie Em, Uncle Henry, the farmhands and Professor Marvel stirred to sympathy by the bump on the head she got during the cyclone. Actually, her “home” — the Gale house — is the instrument that propelled Dorothy to Oz. In that sense, she never really left it to begin with.

(READ: Oz Revisited — Part 1: Why We Still Follow the Yellow Brick Road)

In the Baum book, Dorothy explains her homesickness this way: “No matter how dreary and grey our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there than any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place like home.” Thus she acknowledges the lure of faraway places while affirming that her emotional compass always points homeward.

The movie Dorothy articulates little of that nuance. From what we’ve seen of her Kansas, there’s no place like home for drudgery and frustration. Dorothy’s nostalgia is like that of a prisoner who declines his parole: he wishes he were back in his cell. The Joads in The Grapes of Wrath, for all their troubles in California, might not look back to the parched land they left and croon, “There’s no place like Oklahoma.” How’re ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen the Emerald City?

For the movie to propel Dorothy and the viewer willingly back home, Kansas must have something Oz doesn’t. Arthur Freed thought he knew the answer: an orphan girl’s love for her surrogate mother. In an April 1938 memo detailing his thoughts on the project, he described Dorothy as a girl “who finds herself with a heart full of love eager to give it, but through circumstances and personalities, can apparently find none in return. In this dilemma of childish frustration, she is hit on the head in a real cyclone and through her unconscious self, she finds escape in her dream of Oz. There she is motivated by her generosity to help everyone first before her little orphan heart cries out for what she wants most of all (the love of Aunt Em) — which represents to her the love of a mother she never knew.”

(READ: Oz Revisited — Part 2: Making The Wizard Wonderful)

Freed’s memo brandishes some acute psychology — and proof that he knew from the start that this would be more than a kid-centric fantasy musical — that is not evident in the movie. The “circumstances” Freed refers to must be the absence of Dorothy’s parents and the and the “personalities” those of Auntie Em and Uncle Henry. The film makes no allusion to Dorothy’s real mother (or father); her orphan status must be a condition she long ago accepted. And as played by Clara Blandick, her main adult guardian is quite the bitter pill.

Stern of demeanor, the movie Aunt Em is seen smiling only twice: first in a photo that Dorothy carries when she runs away (and which Professor Marvel borrows to “read” her mind), and then at the end, when Dorothy “comes home.” To Em, in her preoccupation with counting chickens, her niece is little more than a barnyard critter under her feet. Heedless of Dorothy’s pleas about Miss Gulch’s intent to abduct and kill Toto, Em admonishes her to go “find yourself a place where you won’t get into any trouble.” That’s when Dorothy sings “Over the Rainbow,” a dream not of maternal love but of freedom from Auntie Em and the rest of Kansas.

We know that many of the Kansans — Miss Gulch, Professor Marvel and the three farmhands — reappear in Dorothy’s dream of Oz. The one major Oz character who could be wholly the figment of her imagination is Glinda. Wise, capable and still as gorgeous as a Ziegfeld girl (Burke, who turned 54 the month the movie opened, was Florenz Ziegfeld’s widow), Glinda is a good — no, a great — witch, and the perfect fairy godmother for a lonely child who hopes against hope for a sympathetic maternal figure.

Could Glinda be the Auntie Em of Oz? Not likely. If the movie’s creators thought so, they would have cast the same actress in both roles. She’s magical but not reliable, materializing and vanishing abruptly, like the sainted mother in the tenderest dreams of any orphan. Harry Potter had such visitations, from the mother he never knew. Back in Kansas, Dorothy must make do with a severe, fault-finding aunt — her own Petunia Dursley. Or maybe the adults will treat her more kindly now, since she may have been in a coma “for days and days.”

(READ: Oz Revisited — Part 3: A Parable of Empowerment)

John Waters was right when he said that the movie “has an unhappy ending.” Of course it does. In a musical, characters express their feelings and spirits through song. In Kansas, only Dorothy sings; the Land of Oz, nearly everyone does, even the Wicked Witch’s soldiers (“Oh ee oh!”). For the girl to leave her musical wonderland, whatever its perils, and return to the status quo, minus the urge to escape its stultifying restrictions, would almost be a lobotomy of the soul.

The tone is even darker in Disney’s 1985 Return to Oz, in which Auntie Em wants Dorothy to get electroshock therapy! In Walter Murch’s bleak fantasy, Oz is closer to a Dust Bowl Kansas. The rocks and walls are evil sentries, the Yellow Brick Road is gray rubble, the Emerald City an archaeological ruin, its citizens frozen statuary. It’s Oz as imagined by Em.

We don’t mean to demonize Auntie Em. She has to run the farm and the family virtually on her own, since Uncle Henry and the farmhands seem lacking in leadership, competence and gumption. Em may well be a woman who feels love for Dorothy but hasn’t the gift of expressing it. And the fact is that, given the dream construction of the movie’s plot, Dorothy has to return home, where it began. We just wish the filmmakers had given the early scenes the smidgeon of appeal that would justify Dorothy’s fervent wish to prefer Kansas over Oz.

Besides, Em isn’t the story’s prime agency of all mischief. At the beginning, which character was responsible for infuriating Miss Gulch, indirectly leading to Dorothy’s exile? And at the end, who jumped out of the Wizard’s balloon to chase an Emerald City cat, forcing Dorothy to forfeit her ride from Oz back to Kansas? The perpetrator is the lonely girl’s best friend: her dog Toto.

(READ: Oz Revisited — Part 4: The Battle Over ‘Over the Rainbow’)

Dorothy may not escape Kansas, but moviegoers can always return to Oz. Of all the estimable movies from Hollywood’s Golden Age, The Wizard of Oz is the one that has never gone out of fashion. Its enveloping fantasy world allows for no contemporary references that would be obscure today. And it requires no apologies for anachronistic views on race, as Gone With the Wind does.

Modern viewers, whose main complaints about old movies are that they are too dark and too slow, needn’t adjust their eyes and clocks to The Wizard. Once Dorothy alights in Munchkinland, the film bursts into riotous color — aside from GWTW, it was the only Best Picture nominee of its year not in black-and-white — and zips along like a Pixar cartoon epic. But with songs, great songs.

Timeless when it was released nearly 75 years ago, The Wizard of Oz is timeless now. Who isn’t eager, at any moment, to soar with Dorothy over the rainbow and into the Merry Old Land of Oz?