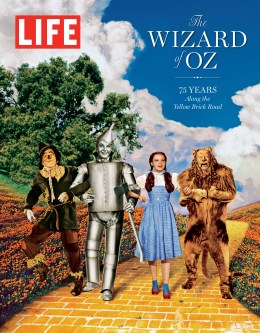

This is the fourth in a five-part series, adapted from an essay in LIFE’s The Wizard of Oz: 75 Years Along the Yellow Brick Road, published by Time Home Entertainment and available on newsstands this week.

Arthur Freed, around the time of The Wizard of Oz, had musicals in his blood, and in his future. In MGM’s early talkie years, he and composer Nacio Herb Brown had written the hit songs “You were Meant for Me,” “You Are My Lucky Star,” “All I Do Is Dream of You” and “Beautiful Girl,” all of which would turn up in the 1952 Singin’ in the Rain. (They wrote that song too.) That was one of a skein of film musicals produced by the Freed Unit, which for two decades married the most renowned American songwriters (Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Leonard Bernstein, Harry Warren and Johnny Mercer, Jule Styne, Lerner and Loewe, Comden and Green) to the finest triple-threat performers in Hollywood or on Broadway — Mickey and Judy, Astaire and Kelly.

A connoisseur, asked to chose the 10 all-time best movie musicals, could arguably go all-Freed: Singin’ in the Rain, plus Meet Me in St. Louis, The Harvey Girls, The Pirate, On the Town, Anne Get Your Gun, An American in Paris (Oscar for Best Picture), The Band Wagon, Gigi (Oscar for Best Picture) and Bells Are Ringing. If by now you’re not humming a song from one of these movies, you must be tone-deaf, or 12.

(READ: Corliss on the Glorious Feeling of Singin’ in the Rain)

In 1938, between his careers as songwriter and movie producer, Freed was working as the uncredited brains behind The Wizard of Oz. In April of that year he had set out his thoughts on the L. Frank Baum story in an important memo that helped shape the texture of the screenplay and the tone of the performances. Now he just had to decide who should write the songs. His first choice was Jerome Kern, the dean of American composers, and lyricist Dorothy Fields, who had collaborated on the sensational score for the Astaire-Rogers Swing Time; and hoped to team them with lyricist Ira Gershwin (whose brother George had died the year before). But Kern had suffered a heart attack and was unavailable. Freed considered two other songwriting duos (his old partner Brown and Al Dubin, or Harry Revel and Mack Gordon) before he and the MGM brass settled on Harold Arlen and E.Y. (Yip) Harburg.

The son of a Buffalo, N.Y., cantor, Arlen had written a slew of hits — “Get Happy,” “Between The Devil and The Deep Blue Sea,” “I Love A Parade,” “I Gotta Right To Sing The Blues,” “I’ve Got the World on a String,” “Stormy Weather” and “Let’s Fall in Love” — all with lyricist Ted Koehler. He first worked with Harburg in 1932 on the Broadway revue Americana. Arlen and Harburg, like Kern, Berlin and Porter before them, had then gone West to write for movies. The money was good, the audience huge; the only thing the songwriters lacked was the authority they enjoyed on Broadway, where they decided which songs went into a show. In Hollywood, the producers were in charge, and most movie musicals of the ’30s (Swing Time included) contained only five or six songs, instead of the dozen or more in a typical Broadway show.

(READ: our review of the Mickey Rooney & Judy Garland — and Arthur Freed — DVD Collection)

The Wizard of Oz would be different. It’s a full score of eight pieces, some divided into sections, like the elaborate “Munchkinland Medley” (which contains seven discrete musical themes) and the three “If I Only Had a Heart / a Brain / the Nerve” solos. Elegantly constructed, yet hummable by any child, these numbers drive the narrative rather than simply ornamenting it. (Harburg also contributed to the screenplay by culling early script versions for retrievable shreds and by writing the Wizard’s climactic awards ceremony.)

Identified with the bluesy numbers he had composed for Ethel Waters and Cab Calloway at Harlem’s Cotton Club, Arlen didn’t approach this adaptation of a children’s book by writing down to the kiddies. Most songs are in a major key, and the jazz inflections are muted — the score’s one boogie-woogie number, “The Jitterbug,” was cut during production — but Arlen’s melodies are as intricate as ever. Harburg had free rein to exercise his lyrical wit in pinwheeling wordplay for the Munchkins and the Scarecrow, Woodman and Lion. The song cycle in the early Oz scenes is musical story-telling of the highest, most effervescent order: Glinda’s “Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are,” Dorothy’s “The House Began to Pitch” (for which Harburg confected nine “witch” rhymes), the Munchkin Mayor and Coroner numbers, the Lullaby League and Lollipop Guild trios, “We Welcome You to Munchkinland” and the celebratory “Ding! Dong! The Witch is Dead.” (Songs for the Wizard and the Wicked Witch of the West were proposed but never written.)

(READ: A Hundred Years of Harold Arlen)

Freed and Arlen agreed on the need for a ballad that would connect Dorothy’s confinement in Kansas with the wonders she meets in Oz. In his April 1938 memo, Freed had noted how, in Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which had opened just a few months earlier, “the whole love story…is motivated by the song ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’.” He suggested an early “musical sequence on the farm” that would express a similar longing. That was the challenge for Arlen: write a ballad that’s not romantic — less a love song than a prayer.

One day, as his wife Anya was driving him through Los Angeles, Arlen asked her to pull over in front of Schwab’s drug store. With the car idling, he jotted down a musical idea that would become “Over the Rainbow.” Talk about dramatic: there’s a full-octave jump from the first note (“Some”) to the second (“where”), instantly conveying a vaulting emotion and establishing Dorothy as a woman (lower octave) who is also a girl (upper octave). Later he added a bridge (“Some day I’ll wish upon a star”) of alternating notes, as in a child’s piano exercise, to be sung “dreamily.” Simple yet sophisticated, the tune seemed a gift from above. As Arlen later recalled, “It was as if the Lord said, ‘Well, here it is. Now stop worrying about it.’”

(READ: a review of Judy Garland’s 1961 Carnegie Hall concert by subscribing to TIME)

His worries had just begun. First, Harburg resisted the idea; he wanted the patter songs to carry the story, and he hated that opening octave jump. When Ira Gershwin finally persuaded him of the melody’s merit, Harburg went to work. He reasoned that in Dorothy’s Kansas, “an arid place where not even flowers grow, her only familiarity with colors would have been the sight of a rainbow.” (It also anticipates the movie’s shift from black-and-white to Technicolor.) Edward Jablonski’s excellent biography Harold Arlen: Rhytm, Rainbow and Blue details how Harburg kept trying to drop those first two notes, then hit on the “Some / where” that today seems perfect and inevitable. Gershwin also suggested the song’s kicker, which repeats the first two musical phrases of the bridge (“If happy little bluebirds fly / Beyond the rainbow…”), then soars into ethereal yearning (“Why, oh why, can’t I?”).

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSZxmZmBfnU]

It is a superb song — and the big guns at MGM didn’t like it. Arlen and Freed had to overcome the resistance of the studio bosses, who balked at filming the segment, then cut the song three times during the editing process. As late as a sneak preview in Pomona on Jun. 16, less than two months before the Aug. premiere, “Over the Rainbow” was not in the movie.

(READ: TIME’s 1939 Wizard of Oz review, with no mention of “Over the Rainbow”)

One possible explanation for the moguls’ skepticism is that Garland, in her early films at MGM, had made her rep less as a balladeer than as a jive singer and comedienne, with such numbers as “Swing, Mr. Mendelssohn, Swing” and “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart.” In her solo movie debut, the 1936 short Every Sunday, Judy sings the jazzy “Waltz With a Swing” while her young costar, Deanna Durbin, performs the operatic “Il Bacio.” (Some at MGM wanted Durbin as Dorothy — she’d have been as wrong as their other early favorite, Shirley Temple.)

Garland’s little-girl looks contrasted almost freakishly with her prodigiously mature soprano and intuitive reading of a lyric. In the Roger Edens song “In-Between,” from the 1938 Love Finds Any Hardy, she addresses her awkward adolescence in words that prefigure Dorothy’s restlessness on the Gale farm: “I’m not a child, / All children bore me. / I’m not grown up, / Grown ups ignore me.”

(READ: The 1969 memorial to Judy Garland)

It is precisely Garland’s “in-between” status, as a grown-up child, that helped make her rendition of “Over the Rainbow” so powerful. She was originally to sing it to Auntie Em and the farmhands. When Fleming left to direct Gone With the Wind, King Vidor — who had directed the populist films Hallelujah and Our Daily Bread, both set on farms — took over the shooting of the Kansas material. It was Vidor who purified the number into a votive secret that Dorothy shares with her only friend, Toto, and with the movie audience.

Filmed in just a few shots, and pristinely performed by an unblinking Judy, the scene displays the film’s first and lasting moments of magic — not of wit or color or special effects, but of the ideal fusion of music and lyric, situation and singer. Every listener touched by this song should think of Harold Arlen on that corner in front of Schwab’s, and join him in saying, “Thank you, Lord.”