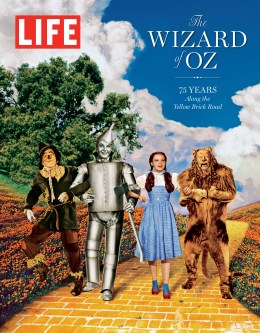

This is the first of a five-part series, adapted from an essay in LIFE‘s The Wizard of Oz: 75 Years Along the Yellow Brick Road, published by Time Home Entertainment and available on newsstands this week.

If you or your grandfather were turning 75 next year, you probably wouldn’t start celebrating now. But the curators of classic popular culture love to jump the gun on anniversaries—especially when the artifact in question is the most beloved movie of all time.

Seventy-five years ago from now, carpenters were building the sets and actors perusing the script of MGM’s The Wizard of Oz. The 16-year-old Judy Garland might have been honing her rendition of “Over the Rainbow,” which she recorded on Oct. 7, 1938. Shooting began on Oct. 13 and continued into the following March. The Wizard had its premiere on Aug. 12, 1939, at the Strand Theatre in the unlikely city of Oconomowoc, Wis., three days before its Hollywood opening at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. So the movie is really only 74 and, say, five weeks.

Nevertheless, the tub-thumping for the picture’s diamond jubilee will become a cheerful corporate din this week. In a 3-D Imax restoration, The Wizard of Oz will invade 318 theaters in 289 cities for a seven-day run, with the big premiere held at the refurbished Chinese Theatre. On Oct. 1, Warner Home Video will release a 3-D/Blu-ray/UltraViolet box set. And did we mention the Time Home Entertainment book?

(MORE: Tim Newcomb on the Newly Imaxed Chinese Theatre)

It was a book that started it all. L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a publishing sensation in 1900, generating dozens of sequels. In 1902, Baum wrote the lyrics and libretto for a lavish stage musical that ran on Broadway for 464 performances. The author also turned the books into a traveling show that he narrated, as the Wizard, with the help of actors, film strips and magic-lantern slides. In 1910 came the first movie version, featuring the young Bebe Daniels in the role of Dorothy. In 1925 another silent-film adaptation appeared, co-starring Oliver Hardy as the Tin Man.

International film remakes have run the gamut from, O to Z, in Japan, Turkey, Russia, Brazil, Mexico and Lithuania. Disney has mounted a sequel (the 1985 Return to Oz) and a prequel (this year’s Oz the Great and Powerful). The Wiz, a black-cast Broadway show, which won a Tony Award for Best Musical and ran for four years, was filmed in 1978 with Diana Ross as Dorothy and Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. The stage musical Wicked, a revisionist tribute to the mean, green Witch of the West, has been entrancing Broadway audiences for the past decade. It will mark its 10th anniversary on Oct. 20.

(MORE: Richard Zoglin’s Review of Broadway’s Wicked)

Yet when most people hear the title The Wizard of Oz, their hearts and minds leap directly to the 1939 MGM film, (most of it) directed by Victor Fleming before he left to direct (most of) Gone With the Wind. Millions of movie lovers warm retrospectively to the Technicolor splendor of the Emerald City, to witches good and evil, to the fearsome Wizard, to Munchkins and monkeys and poppies and Toto too—the whole indelible dreamscape spun from a lonely girl’s fraught wish to be somewhere over the rainbow.

Multiple generations have been enthralled by The Wizard of Oz. People of every age, from toddler to centenarian, know the dialogue by heart. “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” “I’ll get you, my pretty, and your little dog too!” and “There’s no place like home” all grace the American Film Institute’s list of Top 100 movie quotes. Many of Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg’s songs have nestled permanently in fans’ internal jukebox, suitable for retrieval in the most peculiar circumstances. When British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher died in April 2013, her political detractors waged a campaign to propel the Munchkins’ song “Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead” to the top of the music charts. It hit No. 1 in the U.K. iTunes store.

(MORE: The Wizard of Oz Song That Fueled a Margaret Thatcher Postmortem Storm)

Nominated for six Academy Awards, The Wizard of Oz won only two, for Original Score and Original Song (“Over the Rainbow”), plus a richly deserved citation for Garland for “Outstanding Juvenile Performance.” Mind you, 1939 was a vintage year for Hollywood films. Of the 10 finalists for Best Picture, there’s not a clunker in the carload. Gone With the Wind won eight awards, including the big one, defeating three other potent adaptations of famous novels: Wuthering Heights, Of Mice and Men and Goodbye, Mr. Chips. Frank Capra’s populist rouser Mr. Smith Goes to Washington secured a nomination, as did two transcendent weepies, the Bette Davis Dark Victory and the Irene Dunne Love Affair. Foraging beyond the usual stately dramas, the Academy also cited a western, John Ford’s Stagecoach (which made John Wayne a star), and Ernst Lubitsch’s romantic comedy Ninotchka (“Garbo laughs!”); both films are close to being the definitive examples of their genres. Oh, and a musical: The Wizard of Oz.

(MORE: Gerald Clarke on 1939 Movies—12 Months of Magic)

At the 1940 Oscar ceremony, the film got little more than a diploma, a testimonial and a medal. Immortality came later, in the perennial affection of moviegoers and, in the next millennium, a plethora of other awards. Here are just three. In 2001, experts from the Recording Industry Association of America chose “Over the Rainbow” as the best, the very best, song of the 20th century. A 1999 People poll of the century’s favorite movies rated The Wizard of Oz as No. 1, tied with The Godfather. When the British magazine Total Film picked the 23 Weirdest Films of All Time, The Wizard was again, and startlingly, the winner, beating out such authentic indie oddities as Eraserhead, Being John Malkovich, Donnie Darko and Pi. In a way, though, Total Film was simply reflecting the “adult” classification that the British Board of Film Censors gave the film in 1939, “because the Witch and grotesque moving trees and various hideous figures would undoubtedly frighten children.” (Mommy, no! Not the moving trees!) The Imax edition is rated PG for “some scary moments.”

The Wizard of Oz can claim another distinction: it is the rare movie to achieve classic status through annual TV showings. Viewers whom the film had beguiled as children watched it with their kids and on and on through the decades. In 1967, TIME called The Wizard “the most popular single film property in the history of U.S. television,” attracting 64 million viewers when NBC broadcast it in 1970. (In its earlier CBS appearances, when fewer homes had color sets, the movie was aired in black and white, making Oz look like a fizzier Kansas.) It continued to seduce home viewers on VHS and laser disc, DVD and Blu-ray. In a way it never went away. And now it’s back in movie theaters, where a big, colorful film like this should always be seen.

(MORE: See TIME’s 1967 Story on The Wizard of Oz‘s TV Popularity by subscribing to TIME)

“It’s gonna be better in 3-D,” a young woman in Manhattan told her friends before a preview screening of the Imax Wizard. “You’re gonna have the monkeys spittin’ in your face.” Not exactly. The thousand or so technicians who worked for 16 months on the conversion were not trying for the shock effects of a 3-D horror film. They wanted to clarify—or in their words, “optimize”—the original visual elements. And that’s what you get: a clearer view of the freckles on Dorothy’s face, of the rivet between the Tin Man’s eyebrows, of the Scarecrow’s burlap skin. The ruby slippers, shinier than ever, sparkle like a million bucks, which is about what the originals would cost today at auction.

(WATCH: How The Wizard of Oz Got Imaxed)

The transfer of three-strip Technicolor, even with the light-reducing property of 3-D glasses, renders the images nearly as bright as in 1939. And they don’t jump when the camera moves, allowing for the slow, spectacular tracking shot that first reveals Munchkinland in all its floral glory. Unlike MGM’s 1968 wide-screen rerelease of Gone With the Wind, which lopped off the stars’ foreheads in closeups, The Wizard is shown in the familiar Academy ratio; it gives you, literally, the full picture. Technicians also subtly amped up the sound, making the intense moments louder—though at the Manhattan screening, the synchronization of sound to image was off by about a quarter of a second, which was particularly noticeable when Garland sang “Over the Rainbow.”

Other than that, the Imax transfer is everything a purist Ozophile could wish for: It’s as good as old.

NEXT: Part 2 — Making The Wizard Wonderful

THEN: Part 3 — A Parable of Empowerment

FOLLOWED BY: Part 4 — The Battle Over ‘Over the Rainbow’

AND FINALLY: Part 5 — What’s the Matter With Kansas?