Author JK Rowling.

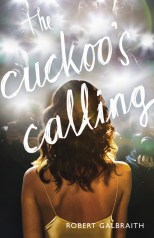

This past weekend, the U.K.’s Sunday Times broke the news that this past April, Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling secretly published a new book, a mystery novel called The Cuckoo’s Calling, under the name Robert Galbraith. The Times was tipped off by an anonymous tweet, and a subsequent investigation turned up the fact that Galbraith—whose bio described him as a former member of the Special Investigative Branch of the Royal Military Police (can fake bios just say anything?)—not only shared Rowling’s agent, but had the same editor and publisher as her 2012 novel The Casual Vacancy.

A Times editor named Richard Brooks took the extraordinary step of submitting the book to computer analysis by two experts, who noted textual similarities to some of Rowling’s other works. Brooks took the evidence to Rowling’s representatives, and she owned up. “I hoped to keep this secret a little longer, because being Robert Galbraith has been such a liberating experience!” she said, in a statement. “It has been wonderful to publish without hype or expectation and pure pleasure to get feedback from publishers and readers under a different name.”

(READ: J.K. Rowling’s Secret: A Forensic Expert Explains How He Figured It Out)

The response was rapid. One publisher bravely admitted that she turned down the book in manuscript. Quite a few authors confessed on social media that they, too, were secretly J.K. Rowling. Naturally, the book instantly shot to the top of online bestseller lists, no doubt to the relief of its publisher, Little, Brown, who for the sake of Rowling’s personal liberation had been sitting on a potential cash cow. To date the book had sold modestly—about 500 copies in the U.S., according to Nielsen; and roughly the same number in the U.K.—but going forward it will certainly sell immodestly. A new Galbraith novel has already been announced for next summer.

The novel’s hero is Cormoran Strike, a struggling private investigator named who lost a leg in Afghanistan. (In retrospect, Rowling’s weakness for extravagant names is a tell; Cormoran is the name of a giant out of Cornish legend, and features in the fairy tale “Jack the Giant Killer”; though it’s hard to resist mentally adding a ‘t’ and turning him into a large, common seabird.) Strike is hired to prove that the suicide of a supermodel known as the Cuckoo was, in fact, the result of foul play — the job takes him into the rarefied, jaded world of the rich and famous.

If nothing else. l’affaire Galbraith is an object lesson in how hard it is to get attention for even a well-received first book. Its slim sales notwithstanding, the reviews of The Cuckoo’s Calling had been almost universally good. The book was widely ignored by the mainstream critics, but the trade magazines, which cover most new releases, loved it. Publishers Weekly called it “stellar;” Booklist called it “absorbing;” and Library Journal called it “totally engrossing.” This is by contrast with The Casual Vacancy, Rowling’s first literary novel, published last year, which was widely reviewed, but not well. The New York Times called it (in the space of one bludgeoning sentence) “willfully banal,” “depressingly clichéd,” “disappointing” and “dull.” (For the record, Time thought the The Casual Vacancy was “brilliant.”)

There’s no question that Rowling is correct to feel that her name carries with it expectations that distort the way anything she publishes is read. Reading is a highly collaborative process, not a passive act but a duet between reader and author — any baggage a reader brings to a book can change his or her response to it radically. In 1979 a would-be writer named Chuck Ross conducted an infamous experiment in which he retyped the entire of Jerzy Kosinski’s novel Steps, which had won the National Book Award in 1969, and submitted it to 14 publishers and 13 literary agents under the name Erik Demos. Every single one rejected it—even Random House, which had published Steps in the first place. Kosinski’s name changed everything. It’s safe to say that no one will ever read The Cuckoo’s Calling the same way again.

The irony here is that for centuries, women have been publishing under male or, at best, ambiguous pseudonyms as an end-run around a sexist literary culture that otherwise would have ignored them. The Brontë sisters did it because, as Charlotte later wrote, “we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.” Louisa May Alcott began her career as one A.M. Barnard. George Eliot’s real name was Mary Anne Evans. Isak Dinesen was born Karen Blixen.

And J.K. Rowling is a pseudonym too: Joanne Rowling, no middle name, adopted it at the suggestion of her publisher, who was worried that boys wouldn’t read a fantasy novel by a woman. Now, in a reversal worth of Rowling herself, she has adopted a male pseudonym for the express purpose of avoiding attention. Which goes to show that even in the world of literature some things do change, and sometimes even for the better. Mischief managed.