In rock journalist Gavin Edwards’ fascinating oral history VJ: The Unplugged Adventures of MTV’s First Wave, four of the music network’s original five “video jockeys”—Nina Blackwood, Mark Goodman, Alan Hunter, Martha Quinn and J.J. Jackson—talk about their experiences working at the fledgling venture. (J.J. Jackson passed away in 2004.)

The four VJs sat down with TIME and shared the story behind the book…and a few tidbits that didn’t make it into the pages.

Here are 32 factoids — one for every year of MTV’s existence — taken from the book and our conversations:

MTV launched on Aug. 1, 1981. The top U.S. single at the time was Rick Springfield’s “Jessie’s Girl.”

Alan Hunter was the first VJ to speak on the network. And the Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star” was the first video the network played.

Yes, sex and drugs did go with the rock and roll. Alan Hunter relates a story in VJ about getting cocaine from J.J. Jackson and having the baggie burst open in his pocket, leading one of the guys hanging out with them to wipe it off the floor of a public bathroom.

But sometimes the scandal was just rumor. In the book, Martha Quinn recalls keeping press clipping that said she was dating David Lee Roth in her scrapbook—because it wasn’t true.

…And sometimes it wasn’t intended for the VJs. Hunter was the recipient of the first nude picture that a female fan sent to the male VJs. But it wasn’t really for him — she wanted him to pass it along to Aerosmith’s Steve Perry.

Getting the VJ gig wasn’t easy. Particularly not for Nina Blackwood. She went to the Tavern on the Green with executive producers who were trying to get her to take the job, and promptly got a roll stuck in her throat. She was saved by the Heimlich maneuver — and took the job.

Being a VJ wasn’t a high-paying gig. Alan Hunter’s goal was to make $550 a week, as much as a Broadway chorus boy. He started off making slightly less than that: $27,000 in his first year as a VJ.

But even the VJs weren’t sure exactly how much they were getting paid. “I had no idea how much more Mark made than me,” Quinn tells TIME. She learned his salary from reading the book.

The VJs didn’t think themselves famous. In fact, they felt like “conduits,” as Hunter says in the book. The closest parallel he can think of is to a traffic cop, directing people to celebrities. That meant the viewers’ relationship with the VJs felt like a friendship—especially because of the nature of cable television at the time. “MTV was the backdrop for everybody’s lives in the ‘80s. [The demographic] was 12–70 because there was nothing else on,” he says. “Even if they didn’t love us, they were like aren’t you that guy from that thing I hate?”

Sometimes the close relationship with fans went too far. Nina Blackwood remembers someone asking for her autograph by shoving a piece of paper into a bathroom stall.

That fan relationship was nurtured by the network. Early MTV techniques mentioned in the book included instructions to avoid saying “all of you” to the TV audience, so everyone watching could feel like they had a one-on-one relationship with the VJ.

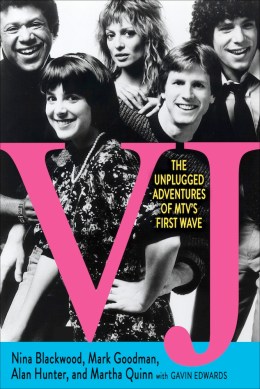

Nina Blackwood, Mark Goodman, Alan Hunter and Martha Quinn in New York City on May 6, 2013

The VJs still get recognized by those fans. But not always as themselves: “I go, ‘I’m Alan Hunter,’ No, that’s not it…” says Hunter, who is often confused for someone the fan went to high school with.

The VJs learned things from their own book. Not just about their salaries. Martha Quinn relates a story about interviewing Bob Dylan and getting invited to come to Ireland with his entourage, where she and his children were in a bus accident. The other VJs had no memory of hearing this story at the time.

Sometimes those secrets were kept on purpose. The VJs recount in their oral history their surprise when Nina Blackwood showed up to work one day wearing a wedding ring—though she still insists that Martha Quinn also got married in secret. (Quinn’s marriage was post-MTV, so she says that’s different.)

But some of the best stories aren’t in the book. Like this one, from Quinn: “I was eating with my parents at a steakhouse and we were just sitting there and this little group comes in, four guys. I say to my parents, ‘Oh my God, that’s Bruce Springsteen!’ and it was way, way early days. My dad’s like, ‘Who?’ I said, ‘He was just on the cover of TIME magazine!’ I was pointing him out. Then Bruce leans over to me and he goes, ‘Hey! I’ve seen you on that MTV.’ I said, ‘That’s more than I can say for you! When are you going to make some videos?’ We all laughed but I think I had an impact, because when Born in the USA came out, boy did he have videos.”

Cable television was a different animal in 1981. As related in VJ, MTV’s stars traveled the country to help personally persuade cable operators to carry the network.

The secret to MTV? Maybe it was the Cold War. ‘80s nostalgia is perhaps due to the “hysterical joy” of the time period, says Quinn, and she traces that to the Cold War, something that doesn’t come up in much nostalgia-bait: “We kind of it that now, looking back at the ‘80s, but Pink Floyd ‘s “Mother do you think they’ll drop the bomb” or Prince saying they’re going to drop the bomb and we’re going to party —there was so much, even in our music, about the bomb,” she says. “I almost feel like the wild colors and the wild hair was a desperate happiness. Once that Cold War started to dissipate that hysterical happiness started to dissipate. Then Curt Kobain came along and made everyone feel stupid. And it’s interesting that Curt Kobain came along when the political climate started to feel safer.”

J.J. Jackson, who died in 2004, “had the wildest stories of anybody,” says Nina Blackwood. Jackson, to whom the book is dedicated, was a fatherly figure, says Hunter, but also in some ways the coolest: “This was his town. Whenever I was trying to get into a club, I just said ‘J.J. Jackson’ and it’s ‘come on right in.’”

But Jackson almost quit at the beginning. The book reveals how, as a serious music expert, Jackson was disgusted when an executive told him that none of the viewers would care about blues guitarist John Lee Hooker.

The most common question the VJs get asked today is whether they’re really friends. Once and for all: yes. Blackwood doesn’t get to see the others as often, since she lives in Maine and only recently got a computer, but they are definitely friends.

MTV’s not-just-music programming of today might be due to Michael Jackson. In a section about the network’s deliberations on whether to show Michael Jackson videos, Martha Quinn mentions how, before that, the station used a radio model for formatting: MTV was a rock network and only played rock music. According to the theory in the book, Michael Jackson’s videos couldn’t be ignored, forcing MTV to open themselves up to pop music (and, ultimately, every kind of music and then shows about music and finally shows not really about music).

MTV’s influence is deeper than you might imagine. The rise of music videos often gets credit for short attention spans and jump-cut editing, but Mark Goodman says there’s more: advertising, movie soundtracks and even literature. “Bret Easton Ellis was writing stuff like what you were watching on MTV,” he says. Alan Hunter adds that the rise of reality TV and “the 15-minutes-of-fame syndrome” can be traced to early MTV spring break programming.

Some of the VJs like—or at least tolerate—the programming MTV has these days… “From our generation, we hear a lot of people saying they want their MTV back,” says Martha Quinn. “My feeling about that is that even if MTV had never ever changed formats and was 24/7 music, what it would be today is Arcade Fire and One Direction and Taylor Swift and people would still be saying it’s no good. It’s not like they’d be playing Duran Duran and Def Leppard. Those days are gone, no matter what.”

“I think it’s evolution,” agrees Alan Hunter. “It had to change. The video jukebox was losing its luster. The novelty had worn off.”

…And some don’t. “I’m just very disappointed that it went away from music,” says Nina Blackwood. “Why didn’t they leave MTV as a music-driven channel? I went there because of the music, not the TV.”

“YouTube is the substitute MTV,” says Mark Goodman. Videos suffered when they lost some of their audience in the pre-YouTube days, but now they’re back. The difference is that YouTube lacks the VJ figure, the person who tells you what to watch.

They’re also betting on satellite radio. All four of the surviving original VJs work as ‘80s-music DJs on Sirius.

The TV on which the VJs saw the premiere of the network didn’t even have stereo sound. As they recount in the book, that was supposed to be a selling point for the network. They also had to go to New Jersey to watch because Manhattan cable providers didn’t carry MTV.

And they keep busy beyond that outlet as well. Blackman hosts two syndicated shows through United Stations Radio Networks. Quinn is a full-time mom. Goodman is managing his 20-year-old daughter’s career. Hunter has an independent film company and is currently pitching two reality shows. “It’s kind of weird to go back to your employer and have the young pups in charge,” he says of pitching to MTV. “I walked in like, ‘How you doing there, sonny?’”

But they’re not optimistic about the music industry. “It’s gonna collapse,” says Goodman. “The labels will be gone. Not in five years, but they’re crumbling now. It’ll be even more so about individuals being able to do it on their own.” He predicts that country-influenced music will dominate because it tends to be less “disposable” in terms of lyrics and message.

The VJs have an eclectic selection of modern-day favorites. Martha Quinn? Lana Del Ray, “but I have a teenager.” Alan Hunter? Skrillex. Mark Goodman? Imagine Dragons. Nina Blackwood, meanwhile, still likes classic rock best.

MTV fans may get to see the VJs’ story on the big screen one day. The VJ-history project was actually first envisioned as a movie, before it became a book, and that hasn’t been ruled out. It would be an Almost Famous-style look at the ‘80s, says Hunter.

And if that happens, one thing is for sure: there will be body hair. “If they were to make a movie of the story of MTV, the one thing I would say to Hollywood is if they’re gonna cast guys in hair bands or bands in general, they have to have body hair,” says Martha Quinn. “No man-grooming for ‘80s movies!”

(MORE: Internet Saved the Video Star: How Music Videos Found New Life After MTV)