A crew member in front of the 'Star Wars Uncut' installation at Storyscapes during the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival on Apr. 18, 2013 in New York City.

The idea of a movie director as a solitary artist sitting in a canvas-backed chair and yelling into a megaphone is being challenged in a new component of the Tribeca Film Festival called Storyscapes. This year’s five entries, on view in a lower Manhattan space, are thought-provoking experiments for which the directors include an engineer, a computer program, and a little cardboard robot on wheels. And they’re not just challenging the image of the director: each one also represents work from filmmakers who have moved past the concept of asking fans to help fund their projects, and have begun asking them to contribute ideas.

It’s an intersection of creativity and technology that the festival organizers are putting forward as the next major development in filmmaking—even if it means changing the definition of a filmmaker.

* * *

The aforementioned robots are part of Robots in Residence, a project that uses cute little droids—and humans’ willingness to open up to robots, even when they ask awkward questions like, “What is the worst thing you have ever done to someone?”—to collect stories that will be turned into a documentary about human-robot relations. The computer program is part of This Exquisite Forest, an exquisite-corpse-style project that collects animation from users. The engineer is former Vimeo employee Casey Pugh, who started Star Wars Uncut, a shot-by-shot remake of Star Wars using crowdsourced 15-second scenes.

Those three projects are alongside Sandy Storyline‘s collection of narratives from Hurricane Sandy and A Journal of Insomnia, an interactive piece produced by the National Film Board of Canada that collects testimonies from insomniacs and allows them to interact with the documentary’s “characters,” who are also losing sleep, via a website that only functions at specific late-night times.

(MORE: Robert De Niro and Jane Rosenthal On The Digital Future of Film Festivals)

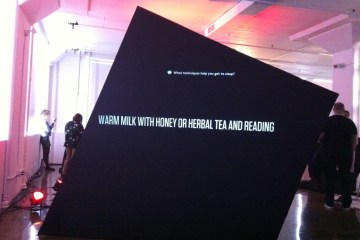

The ‘A Journal of Insomnia’ installation at Storyscapes at the Tribeca Film Festival on Apr. 18, 2013, in New York City

The insomnia project—the Tribeca installation of which includes a giant black box, made of spandex on a frame, in which insomniacs can share their thoughts—is just one of the National Film Board’s interactive projects, which now comprise 25 percent of NFB activity, according to Monique Simard, director general of the Board’s French program. And even that number is conservative, as the other three-quarters are starting to take on interactive qualities. “I come from traditional film,” she says, “but I’ve been noticing over the last two years that the way [the interactive projects] work is influencing our other studios.”

Not that the fully interactive projects aren’t movies, says A Journal of Insomnia co-creator Philippe Lambert. “It’s a new form of documentary,” he says, not a website. “It’s anti-internet, to tell people to come at a certain time. It’s filmic because you want people to go to it [like they go to a movie].”

But, despite the collaborative nature of the content production in the Storyscapes projects, those who contribute their time or stories or animations are not generally considered filmmakers. Casey Pugh’s Star Wars Uncut project—which began with A New Hope in 2008 and is currently in the process of creating The Empire Strikes Back—started as an experiment in how to help filmmakers work together remotely, but at this point Pugh sees it as his “personal project.”

Those who chip in by creating a 15-second scene get their names in the credits but they know going into it that anyone who submits a chunk of The Empire Strikes Back is giving their work free of charge to LucasFilm and Pugh. “When I first started I thought of myself as an engineer working on a cool art experiment. I failed to realize it was going to be a real film at the end. To be called a director is like, ‘That’s interesting,'” he says.

(MORE: Internet Cats: Behind the Memes)

Pugh says that he’s aware there’s a negative way to look at his experiment, as a cheap way to get a lot of people to do your work for you. But he sees it differently, as “tapping into the creativity of the world,” and looking at the Storyscapes projects as art—especially considering part of This Exquisite Forest will end up in the Tate Modern—makes that argument convincing. After all, Star Wars Uncut is not the first art experiment to collate clips produced by other filmmakers. Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a 24-hour film composed of views of clocks seen in other movies, has won broad acclaim (and a spot on last year’s TIME 100) for the artist.

Where that calculation may change is if the techniques and technologies seen at Storyscapes continue to do what Monique Simard is already seeing, if they creep into commercial blockbusters, if the collectors of crowdsourced content stand to make a great deal of money from the work of others.

* * *

There’s already evidence of trend-leakage elsewhere at the Tribeca Film Festival: Tricked, a new movie from Robocop and Basic Instinct director Paul Verhoeven, screening at the festival tonight, Apr. 23. Tricked is part of the festival’s director talk-backs series, not Storyscapes, but the process behind the movie will sound familiar. Verhoeven wrote only the first four minutes of the movie and then invited fans to send in ideas and scripts for the rest of it. The finished film is a combination of the movie that resulted from the project and a making-of documentary; although the film is not exactly mainstream, it already had a theatrical release in the Netherlands and has one planned for the U.S. in October.

Beyond the questions of finance and fairness, and even if crowdsourced movies remain the province of art museums rather than cineplexes, the installations at Storyscapes raise a larger question about the nature of art—one that has a slim chance of being answered by a single film festival. The common conception of the artist involves creating, but a broader view of artistry has long been approaching, from the visual art of appropriation created by people like Richard Prince to the remixes made by successful DJs.

Technology allows people like Philippe Lambert and Casey Pugh to gather content faster than their predecessors could have imagined. In the case of Robots in Residence, programming within the robots even allows the machines to sort film clips (by length, for example) before a human being ever touches them. None—except an offshoot of This Exquisite Forest that will not end up in the Tate—are devoid of human oversight, but the directors don’t have any control over what gets created. Instead, they control what portion of the material is good enough to include. It’s as if the infinite monkeys with typewriters—the ones in the famous thought experiment that says they would eventually produce Shakespeare’s work—had an editor. The combination of fans and machines becomes an artist; the artist becomes the curator.

But art-by-algorithm isn’t necessarily a vision of dystopia. In a way, the world is demanding it, says Tribeca Film Festival programming director Genna Terranova. The Storyscapes projecsts aren’t so far from tweeting during the Oscars or making a fan video on YouTube about your favorite TV characters: modern audiences expect to be able to interact with entertainment rather than just receive it, inviolate, from an auteur. Seen in that light, crowdsourced content is the logical extension of that interaction—and it’s a trend that is already well underway.

“Even with crowdfunding, you see that people really want to be a part of something creative, whether it’s theirs or not,” she says. “Just like there was an independent film movement, there’s a movement going on where people are taking new technology tools and telling stories in a different way.”