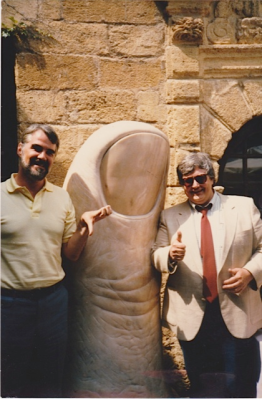

Roger Ebert, right, with Gene Siskel

He went out fighting, and writing.

Roger Ebert, the Pulitzer Prize–winning film reviewer for the Chicago Sun-Times, and something of a TV star for his 31-year series of critics’ klatches with Gene Siskel and Richard Roeper, had been battling cancer for seven years. In several early operations, he lost most of his jaw to throat cancer, robbing him of his vocal cords but not his assured authorial voice, which, since his 2006–07 surgeries, has rung out in at least a thousand reviews and a poignant, clear-eyed blog about his illness. In December, he suffered a fall and discovered the disease had metastasized to his leg. Still, he kept blogging and reviewing. Then, on Tuesday he announced “a leave of presence”:

Thank you. Forty-six years ago on April 3, 1967, I became the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. Some of you have read my reviews and columns and even written to me since that time. Others were introduced to my film criticism through the television show, my books, the website, the film festival, or the Ebert Club and newsletter. However you came to know me, I’m glad you did and thank you for being the best readers any film critic could ask for.

Typically, I write over 200 reviews a year for the Sun-Times that are carried by Universal Press Syndicate in some 200 newspapers. Last year, I wrote the most of my career, including 306 movie reviews, a blog post or two a week, and assorted other articles. I must slow down now, which is why I’m taking what I like to call “a leave of presence.”

What in the world is a leave of presence? It means I am not going away. My intent is to continue to write selected reviews but to leave the rest to a talented team of writers handpicked and greatly admired by me. What’s more, I’ll be able at last to do what I’ve always fantasized about doing: reviewing only the movies I want to review.

At the same time, I am re-launching the new and improved Rogerebert.com and taking ownership of the site under a separate entity, Ebert Digital, run by me, my beloved wife, Chaz, and our brilliant friend, Josh Golden of Table XI. Stepping away from the day-to-day grind will enable me to continue as a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, and roll out other projects under the Ebert brand in the coming year …

The immediate reason for my “leave of presence” is my health. The “painful fracture” that made it difficult for me to walk has recently been revealed to be a cancer. It is being treated with radiation, which has made it impossible for me to attend as many movies as I used to. I have been watching more of them on screener copies that the studios have been kind enough to send to me. My friend and colleague Richard Roeper and other critics have stepped up and kept the newspaper and website current with reviews of all the major releases. So we have and will continue to go on.

It’s sweet and typical that Roger would begin with “thank you.” His connection with readers was a communal, reciprocal pleasure. Rare for a critic, he was as interested in other people’s opinions as his own. Roger was startlingly at ease with his celebrity, never shriveling in the limelight, always amicable to strangers who approached him at film festivals. He was sharing his thoughts on the Internet before friend was a verb; today, his Twitter following numbers 841,148. And never, not ever, did he suffer from writer’s block, which must have made his enforced silence during the year of his calamitous surgeries a hell of several kinds.

(MORE: Corliss’s 2007 Tribute to Roger Ebert)

For the rest of his 46 years as a critic, Roger streamed millions of words, by voice or print, by digital or social media. He could not have achieved this ceaseless prodigality if he did not also have an enlightened capitalist’s organizational mastery of his midsize empire of journalism and movie love. You don’t build a career like his — actually, there was no career like his — without optimism, discipline and a sharp business sense. He made millions and earned every penny.

True to the man, Roger’s Tuesday message was a public declaration of defiance that cancer had not defeated him. “I am not going away … [We] will continue to go on.” His “leave of presence” allowed him to concentrate on some big plans: for the fourth in his series of books about The Great Movies; for the 15th annual Ebertfest, to be held in two weeks in his long-ago college town of Champaign, Ill.; for the documentary film being made about him by Hoop Dreams’ Steve James; and for the future of his popular and essential website, rogerebert.com.

(MORE: Steven James Snyder’s Coverage of the 2009 Ebertfest)

Courtesy of Mary Corliss

Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss at the Colombe d’Or restaurant in St-Paul-de-Vence, France, late 1980’s. The thumb sculpture is by César Baldaccini.

This afternoon and this evening, the site was frequently inaccessible because of heavy traffic. His myriad admirers may have gathered there — as mourners for other famous figures had gravitated to Buckingham Palace or the Dakota — to register their grief at the news they had read elsewhere: that Roger Ebert was dead at 70. As President Obama said today, “The movies won’t be the same without Roger.”

So the Tuesday message was a bluff, a final you-got-served taunt to mortality, as it loomed at his bedside. Roger leaves a legacy of indefatigable connoisseurship in movies, literature, politics and, to quote the title of his 2011 autobiography, Life Itself. As a critic, he was more famous than most of the actors and directors he wrote about. And in his last seven years, when he endured more outrages of fate than Job, he demonstrated with grace and grit how a man’s spirit could flourish as he tried to outthink Death.

A Life for the Movies

“I was born inside the movie of my life”: the opening words of Life Itself announce both the crucial cinematic lure of magic images on a big screen and Roger’s talent for analyzing his own adventures and limitations. Given his gift of gab, that movie must have been a talkie. He fits William F. Buckley Jr.’s description of Roger’s fellow Midwesterner Rush Limbaugh: “preternaturally fluent.” One imagines him popping out of the womb and saying, “Hi, Mom! Well, that was an interesting nine-month movie I just sat through. The visuals were lacking; it was more like radio, really. But the soothing darkness well prepared me for a life of sitting in movie theaters. All in all, I give the experience two enthusiastic, tiny thumbs up!”

(MORE: Why Roger Ebert’s Thumb Mattered)

Roger went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he was editor of the Daily Illini. He spent an illuminating year on a fellowship in Cape Town, where he saw the inequity of racism and disposed of his virginity courtesy of a friendly hooker. But, Midwestern to the core, he dreamed of Chicago as Dorothy did of the Emerald City, and in 1966, he got a job at the Sun-Times. For years, he was the image of the hard-drinking newspaperman, back when that tag was nearly a redundancy. He took his last drink in 1979 and joined Alcoholics Anonymous, which in Life Itself he calls “the best thing that ever happened to me.” That is one of the book’s few errors of fact. His life’s miracle has been his 21-year marriage to attorney Chaz Hammelsmith, whose love, he writes, “was like a wind pushing me back from the grave.” By keeping her man going in his darkest year, Chaz is revealed as the true hero of both Life Itself and Roger’s life.

Mary Corliss and I are grateful that we were part of that life for 40 years. In 1972, he wrote a piece on the gifted, gonzo sexploitation director Russ Meyer for Film Comment, a magazine I edited. Actually, my first impression of Roger is earlier than that: 1970, when I saw Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a thrillingly gaudy Hollywood exposé/comedy/musical/slasher film that the 27-year-old Roger had co-scripted. In the pages of National Review, where I was a movie critic, I named Beyond the Valley of the Dolls as one of the 10 best films of the 1960s. As amused as he was amazed by the citation, Roger would frequently refer to it, if only to raise doubts in the minds of listeners about my own critical acuity.

(MORE: Corliss’s Review of Roger Ebert’s Autobiography, Life Itself)

Over nearly four decades, Mary and I would catch up with Roger at film festivals. At Cannes in the ’70s, we spent many an hour with him on the cocktail terraces of the Majestic and Carlton hotels, for his voracious interest in films of all kinds occasionally took a back seat to his fascination with the outsize showbiz figures that roamed the Croisette. Roger’s friendship with Toronto International Film Festival co-founder Dusty Cohl made him an early TIFF champion; he and Siskel would host the gala filmmaker tributes, cheerfully grilling the likes of Woody Allen and Warren Beatty. In 1991, Cohl launched his own Floating Film Festival, a biennial cruise on which Roger, Chaz, Mary and I were among those who presented our favorite movies to a couple hundred cinephiles and their husbands. There, he held five-hour sessions where he’d show some classic film, Citizen Kane or The Third Man, stopping the action during each scene to offer his original commentary. It was called Democracy in the Dark, and he was the enlightener.

A few other memories: the only time that Mary and I saw Roger in Manhattan, our hometown, was a night in the late ’70s when the three of us went to the sex club Plato’s Retreat, as observers only, tiptoeing on a boardwalk in the middle of the room as women and their hairy mates in socks took their pleasures. (A pity no blog existed then for Roger to record his impressions.) In London, probably in the late ’80s, we hooked up to go on a stroll through Highgate Cemetery; polymath Roger — also a scholar of English history, literature and grave sites — was leading the tour. It was raining so hard that the whole group bought plastic bags to wrap around our shoes; and I recall standing in four inches of muddy water in a tomb and hearing the friendly local guide trill, “Mind the rats!”

(MORE: Michael Scherer’s Tribute to Roger Ebert)

Our friendship endured a little bump in 1990 with a Film Comment piece I wrote about the Siskel & Ebert show. I knew its popularity was rooted in the two men’s clashing, odd-couple personalities, and that the show was really less a salon of cinema criticism than a sitcom about two guys who lived in a movie theater. But I managed to find it guilty of reducing the sacred art of film criticism to a plot synopsis and two thumbs — “up” for favorable, “down” for a pan — as if he and Siskel were Roman emperors deciding a gladiator’s fate. Roger responded to my raillery in good humor, defending his show without calling me an ignorant slut. I never felt a reduction of amity; we were colleagues who had agreed to disagree; and a few months later we were merrily gassing away at the Telluride Film Festival.

At the 2006 Cannes festival, Roger, Chaz, Mary and I walked from our favored hotel of many decades, the Splendid, to the Martinez, where a screening of some scenes from the forthcoming Dreamgirls were to be shown. The line was long when we arrived, and the guards wouldn’t let us in. For once, I saw Roger mildly annoyed. “Don’t they know who I am?” he puffed. “No, honey,” Chaz replied. “We’re in France, they don’t know who you are.” Feathers smoothed, we got in, saw the rushes and repaired to La Pizza, one of Cannes’ iconic eateries, for one of our loveliest evenings. Roger mentioned that he had to return to Chicago for a little surgery. No problem, he’d be back on his TV show in a few weeks.

(MORE: A Tribute to Roger Ebert From His Onetime Sun-Times Editor Steven S. Duke)

In a way, his determination that the show must go on may have killed him. When he was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the best specialists prescribed a conservative treatment. Roger nixed that in favor of more experimental neutron-radiation surgery — he found it on the Internet — which, if successful, would speed him back on the air. That surgery, and two others, failed, leaving him without a jaw, unable to speak, eat, drink or sleep in a bed. In his Siskel & Ebert days, he was known as “the fat one” — in his words, “the Michelin Man.” After his surgeries, he wrote in Life Itself, he looked “like an exhibit in the Texas Chainsaw Museum.”

The onslaught of crippling illnesses, and a radical new look that caused waves of shock and sympathy when his photo appeared in Esquire in early 2010, might have turned anyone else into a hermit. But with a showman’s bravado and a survivor’s heroism, Roger kept appearing at film festivals, escorted to his seat usually by Chaz, occasionally by her granddaughter Raven. He continued filing reviews, and communicated with friends through hands signals (a thumbs-up meant yes), scribbled notes and a series of talk boxes like the TED2011. Mary and I still dined with him in Toronto and Cannes, and served as two of his surrogates at the 2008 Ebertfest. Last month I sat for an interview with Steve James for his Roger doc, to be called Life Itself.

(VIDEO: Roger Ebert and His Wife Discuss His New Way of Talking)

Why did Roger go public? Because he knew that, in movies, Show was as important as Tell, and that the value of that photo would be therapeutic, alerting the world not just to his plight but to his steely will to confront it. And the Tell was even more eloquent. His writing, always briskly assured, gained a maturity and sustaining wit as he contemplated his condition; he appraised it almost as if it were a movie: a thing to be observed in all its facets and appraised with a passionate curiosity. By awful chance, he had found a great subject, and he raised his game to give it both personal and poetic justice. And by great luck, he had Chaz, a profile in courage who refused to let her man give up. Her love, Roger wrote, “was like a wind pushing me back from the grave.”

In Life Itself, Roger contemplated his demise: “I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear. I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path. I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state. What I am grateful for is the gift of intelligence, and for life, love, wonder, and laughter. You can’t say it wasn’t interesting.” You can’t say he didn’t make it more interesting for the rest of us.

(MORE: Roger Ebert’s Dissenting Opinions)

So Roger has taken a permanent “leave of presence” — as if his work as a critic could ever be absent from the film lover’s mind, or his heroic battle with the cancer beast can be far from our hearts. The movies won’t be the same, the President said. And neither, for Roger Ebert’s world of friends and fans, will life itself.