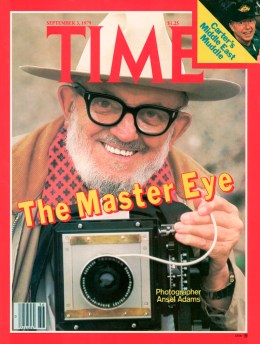

ISSUE DATE: Sept. 3, 1979

THE BUZZ:

In a big redwood house above the shifting kelp beds and nocturnal sea of Carmel, an old man is playing the piano, not too well. The room is large, worn and comfortable, decked with the heterogeneous souvenirs of a long life—rows of Indian pottery, elegantly woven tribal baskets and a huge Chinese ceremonial drum. The piano player’s head, a bald mass, gleams in the light. His hands, swollen from arthritis, hardened by decades of immersion in darkroom chemicals, skitter over the keys, assaulting the same phrase again and again. “Damn,” he says, “I’ve lost it.” But not altogether. Once you have practiced to concert discipline, even 50 years ago, the traces still show. “There used to be a relationship between my piano and my photography,” says Ansel Adams. “I guess it’s one-sided now.”

Today, at 77, Ansel Adams is the most popular “fine” photographer in America. His images of landscape, and particularly of Yosemite National Park in California, have become almost indistinguishable from their subjects: to many people, Yosemite is the apparition on Adams’ viewfinder. “Won’t it be wonderful when a million people can see what we are seeing today!” exclaimed John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club, as he gazed on Yosemite seven decades ago. Last year 2.7 million tourists went to Yosemite. One may fairly assume that most of their innumerable frames of 35-mm and Polaroid film were exposed in the hope of trapping their own Ansel Adams image, rather as tourists in 18th century Italy sometimes carried a smoked lens called a Claude Glass, through which the landscapes of the Roman Campagna could be seen in the mellow brown tone of Claude Lorrain’s canvases. To that public, Adams is as American as John Wayne: the last portraitist of Western sublimity.

Read the full story here