(Lev Grossman writes about books here on Wednesdays. Subscribe to his RSS feed.)

I love rare books. Not that I own a lot of them, mind you. You couldn’t quite call me a rare-book collector. But I did once work in a rare-books library, and I wrote a novel about a rare book. And I was once married to a rare-books dealer. So I’ve checked off a few of the boxes anyway.

But the books I collect are mostly not all that rare. They don’t tend to have a lot of value, in the monetary sense, because I personally don’t have a lot of value in the monetary sense.

My specialty as a collector is books that almost have value. When I love a book, I don’t buy the first edition, because those have become incredibly expensive. But I might buy a beat-up copy of the second edition, third printing, which looks almost exactly the same as the first edition except that a couple of typos have been fixed. (In the rare book trade the little details that definitively identify a first edition are called “points.” My books are not strong on points.) It’s not glamorous, but it’s still satisfying, and it’s a hell of a lot cheaper.

And once in a while I have lucked into an actual first edition, just to make things interesting. So come on! I’ll give you a tour. Here are a few of the highlights.

Lev Grossman for TIME

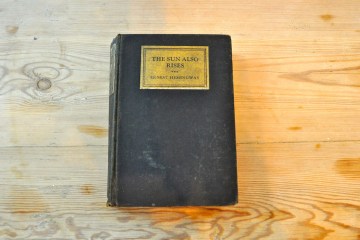

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

The Sun Also Rises was published in 1926. True first editions are recognizable by—among other points—a misprint on page 181: “stoppped” instead of “stopped.” This copy doesn’t have that. True first editions aren’t dated 1927, either, as this one is, and it’s in terrible condition, but it’s still a pretty early copy, dammit, and it’s my best “find” of an unusual old book in the wild: I bought it for two dollars at a used bookstore in New Haven, CT in 1995. For a few hot minutes I thought I’d made the find of the century—a real first edition of The Sun Also Rises recently sold for $78,000. No such luck. But it was pretty to think so.

Lev Grossman for TIME

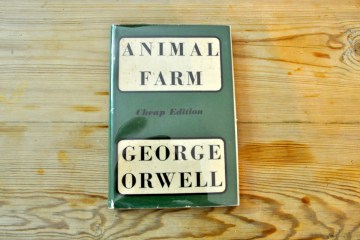

George Orwell, Animal Farm

The “Cheap Edition”! Says so right on the cover. Beautiful book design. This copy was printed in 1951, six years too late to be a first edition. Actual worth? About ten bucks. I love it anyway.

Cicero, Oratione (three volumes)

I have no idea if it’s worth anything, but this is still an amazing book. It belonged to my father, a poet and English professor, who bought it when he was in college and gave it to me one night a few years ago, apparently on the spur of the moment. The title page says it was printed in 1541 in Venice by Paulus Manutius, son of Aldus Manutius, the legendary printer who invented italics. Printed books had existed in the West for fewer than 100 years when this one was made. This particular copy seems to have belonged to the Vatican at some point; at any rate it was rebound and the words “nel Ven. Seminario Vaticano” (whatever that means) written on it in an amazing calligraphic hand. Eventually it must have been de-accessioned and caught some unlucky breaks and wound up with a sidewalk vendor in Chicago, where my father says he bought it for $15. It does have that price written on the first page in pencil, so maybe that’s true. At any rate it’s a beautiful set. Unfortunately I will never read it, because my Latin is terrible.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Mrs. Dalloway was first published in 1925. And this copy is copyright 1925! But it’s not a first edition. It’s an American edition—it was published by Harcourt, Brace and Company—and I think the British edition preceded it. Though it could still be a first American edition—if you Google “Mrs. Dalloway ‘first American edition'” you get a lot of books that look exactly like this one. I don’t know for sure, because I can’t figure out what the “points” are. But if it were an American first I would probably remember where and when I bought it. And I have no idea.

Lev Grossman for TIME

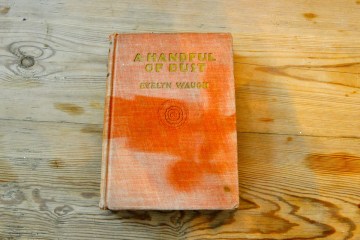

Evelyn Waugh, A Handful of Dust

This is a first American edition, or at least I think it is. Last year I gave a reading at a new-and-used bookstore in New Jersey that had this copy in its rare-books case, billed as such (unless I’m misremembering; there was whiskey involved). The bookstore was closing the next day. I tried to buy it, but the bookseller very generously pressed it on me as a gift instead. I tried to refuse. I failed.

Lev Grossman for TIME

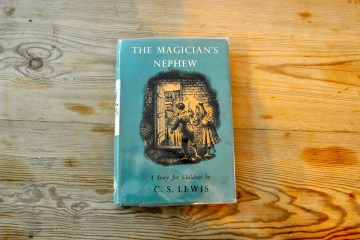

C.S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew

And now we come to the centerpiece of the collection. Believe it or not, this actually is a stone-cold actual first edition of C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew. I know! Definitely believe that it is my prize possession, and I couldn’t have afforded it on my own. It was a gift, and I only hope that one day I will live to deserve it. When my house burns down, it’s the first thing I’ll grab.

Lev Grossman for TIME

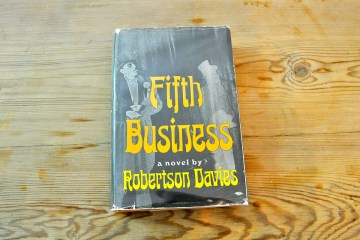

Robertson Davies, Fifth Business

Also a first edition. A gift from my brother for Fathers Day. One of my absolute favorite novels, though like a lot of first editions from this period (1970 is the year) it’s not a beautiful piece of book design. The “point” that identifies it as a first edition, if you’re scoring at home, is a goof in the table of contents: chapters 3 and 4 are listed as beginning on pages 172 and 122, respectively, instead of the other way round.

Lev Grossman for TIME

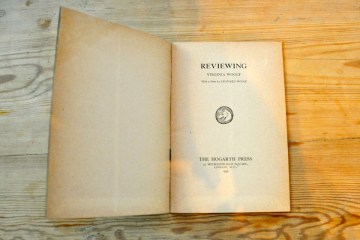

Virginia Woolf, Reviewing

A true beauty, this one, and another actual first edition, printed by the honest-to-God Hogarth Press, operated by Woolf herself and her husband Leonard.

Lev Grossman for TIME

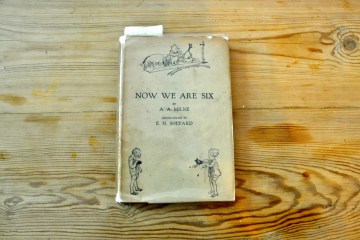

A.A. Milne, Now We Are Six

This copy is from 1927, and it’s clearly identified as the third edition, in case I was tempted to pass it off as anything else. But it’s still one of the most beautiful books I own. It actually belongs to my daughter Lily — a good friend gave it to her as the greatest sixth-birthday present ever. She was a lot more excited about her new bike, but eventually—in about 20 years—she’ll appreciate this one more.

Lev Grossman for TIME

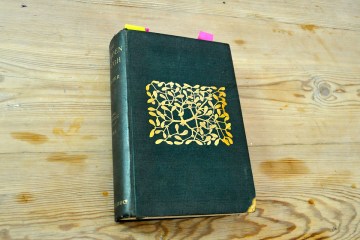

James George Frazer, The Golden Bough

There’s actually 12 volumes to this one, but I couldn’t be bothered to lug the whole set downstairs to take its picture, so this photo is of volume one, resonantly entitled The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings. The Golden Bough is, of course, the vast folkloric/mythological skeleton key that T.S. Eliot consulted while writing “The Waste Land”—Frazer is the great theorist of the dying and reviving god (you know, like Aslan). Google seems to think this set might be worth something, so I should probably take care of it. Interesting trivia: the bookplates carry the name “Ethel Randolph Thayer,” who was, according to Google, a notable Boston-area painter.

Frazer first published The Golden Bough as two volumes, then expanded it to twelve in the third edition, which this is. I rescued it from my father’s library—he has Alzheimer’s now and can’t read anymore, and his books were being boxed up and sold in bulk to a used bookstore. There was no way I was letting this set out of the house. It still has my father’s stickies stuck in it.

It was a sad day—almost like a death in the family. But now this Golden Bough—which was once Ethel Randolph Thayer’s, then my father’s—lives on as part of my collection. I hope it will outlive me and become part of Lily’s collection in turn. I believe in dying-and-reviving gods, but not the Golden Bough kind. The dying-and-reviving gods I believe in are libraries.

MORE: All-TIME 100 Novels