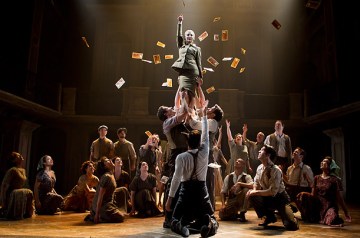

Paul Nolan, center, plays Jesus during a scene from the musical "Jesus Christ Superstar" at the Neil Simon Theater in New York, Feb. 29, 2012.

Let us now remember the days when Andrew Lloyd Webber was more than just a Broadway punch line.

The British composer, you’ll recall, was once the hot new thing in musical theater. Collaborating with lyricist Tim Rice, he virtually invented the rock opera with Jesus Christ Superstar in 1970, and followed it with a string of groundbreaking, gloriously melodic and often long-running shows (one of which, Phantom of the Opera, just passed 10,000 performances on Broadway). If the critics, American ones especially, were always a little wary of him, they’ve become downright scornful as his skills and fortunes have faded. Of his last five shows — Whistle Down the Wind, The Beautiful Game, Bombay Dreams, The Woman in White and Love Never Dies (a sequel to Phantom)— three of them never even made it to Broadway. The other two probably wish they hadn’t.

So it’s gratifying to find Webber’s two greatest shows, Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, back in simultaneous revivals on Broadway. Time for a little belated respect.

The first thing to notice is how fresh, audacious and vibrantly alive the music is. Some stuffy critics once carped that a few of Webber themes sounded like Puccini, which got him forever branded as derivative. But even four decades on, these two shows still sound like nothing else. The screeching guitar riffs, jagged rhythms and wailing intensity of Superstar’s rock score; the bouncy, hyperbolic, Latin-pop lyricism of Evita — next to them, almost any Broadway score today sounds like kids’ stuff. (I’m looking at you, Book of Mormon.)

(MORE: Jesus Christ Superstar Rocks Broadway)

Tim Rice’s lyrics have always been a more divisive issue. For purists, he’s too fond of pop slang, too sloppy about meter and rhyme (“Well, if I HELP you/ It matters THAT you see…”), and he can write some truly awful lines (“I kept my promise/ Don’t keep your distance”). But the faults are a function of his ambition. He was writing sung-through operas (almost unheard of on Broadway at the time) on enormous subjects: the crucifixion of Christ and the rise and fall of Argentina’s rock-star First Lady, Eva Peron. These are stories that call for passion, irony, narrative clarity and political sophistication. In many lyrics, like the ones that launch Judas’s opening soliloquy — “I remember when this whole thing began/ No talk of God then, we called you a man” — Rice does all four compactly, and brilliantly.

The new revival of Superstar, staged by Des McAnuff to much acclaim last summer at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Canada, is a knockout.Visually, it has a sober, industrial look, with a set made up of rolling metal staircases, bleacher seats and catwalks (borrowed, it looks like, from Newsies down the block), and stock-ticker-like LED displays, which keep track of the time. Musically andemotionally, however, the production pulls out all the stops.

I saw an understudy, Jeremy Kushnier, in the role of Judas, and he brought a rich, thrilling tenor that brought out all the angst of the show’s tortured, tragic anti-hero. But the entire cast sings beautifully and takes the show seriously, as it should be. Even the jaunty vaudeville number “Herod’s Song” (“Prove to me that you’re divine/ Change my water into wine”) is given a nervous, bitter spin in Bruce Dow’s snarling rendition. Front to back, it’s the most musically exciting show of the Broadway season.

Sara Krulwich / The New York Times / Redux Pictures

But if the new Superstar soars, Evita doesn’t. Elena Rogers, the smallish Argentine actress who won raves for the role in London, has authenticity (and the Argentine accent to prove it), but little charisma, or sexual allure. Her voice is strong but surprisingly chilly: almost no vibrato and little lyricism in the upper register. It is not a pretty voice. When she got through singing “I’d Be Surprisingly Good for You,” the show’s most beautiful melody, for the first time ever it sounded merely ordinary.

(LIST: Top 10 Plays and Musicals of 2011)

Michael Grandage’s production in almost every way is a comedown from Harold Prince’s great original. The number “Peron’s Latest Flame,” in which the Argentine soldiers and society twits complain about their leader’s new “whore,” is no longer a slickly choreographed block dance, with the two groups alternately marching in contrapuntal units. Now they all just kind of sit around and stamp their feet.

Ricky Martin, the pop star brought in for some marquee value as the narrator, Che, is perfectly acceptable, and Broadway veteran Michael Cerveris brings some real singing chops as Peron. But for all its glorious music, Evita is less an involving drama than a narrated history lesson; it needs a galvanizing star to carry us through the dramatic shallows. And for that, apparently, you have to go back to the old days.

Zoglin, TIME’s theater critic and a former assistant managing editor, is the author of Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America