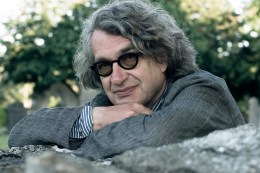

The German dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch invented a new kind of dance — tanztheater, or dance theater — that made her legendary among her peers. She was also known for her intense, familial relationships with the dancers in her corps. The result was a primal, immersive experience. Documentarian Wim Wenders spent 20 years trying to figure out how he could bring the experience of a live Pina show to the screen. When 3-D returned in popularity, he saw his chance. In the process, he may have discovered what 3-D is best at expressing: the voluminous presence of the body. But just before the pair could begin shooting, Bausch died suddenly in 2009 — just five days after receiving an unspecified cancer diagnosis. What began as a work about Pina turned into a work dedicated to her. Wenders spoke to TIME about his film Pina.

How did you first encounter Pina Bausch?

That goes back almost a quarter of a century. I didn’t know much about dance and I wasn’t much of a dance fan when I saw my first piece. I almost had to be forced to see it: my girlfriend insisted that I go with her one evening in Venice to see a double billing of two plays by Pina Bausch. And I really tried to escape that night! In Venice in the summer, you can do great things.

But as a gentleman, I caved in – not expecting much, to tell you the truth. And then I found myself sitting there and after five minutes, I started crying. I couldn’t really help it. I was weeping like a baby throughout the entire thing and I was caught by an emotion that I’d never experienced in front of any stage; any dance, theater, opera, whatever. I didn’t understand it. My body understood it, but my brain was lagging far behind. It took me a while. I had the luck to meet Pina Bausch the next day.

(MORE: The Top 10 Movie Performances of 2011)

Was it difficult to meet her after you’d had such an intense reaction to her work?

Well, I’d had this great, powerful emotional introduction to the work of somebody who, after that night, I felt must be a genius. And there she was sitting in front of me: tall, very fragile, skinny and not saying anything. Not a word. she said “Hello” and that was it! And from there on, I had to talk. And I’m not really talkative, to tell you the truth. But I had to. I had to! Because she didn’t say anything, she just smoked one cigarette after another. So, in my juvenile enthusiasm I started telling her how much I loved it and talked on and on and she looked at me and smiled and didn’t say anything, so eventually I even just said, “One day, Pina, you and I will have to make a film together.” And I thought that would get a reaction, but she only smiled at that as well. So I changed the subject and talked about something else because I thought maybe she thought it was preposterous.

And all through this time that I talked at her, I felt like she was seeing through me – like nobody had ever seen through me. It felt like I could not have a secret in front of her. And that’s another reason why I kept talking. I felt understood by her. When we met again, a year later, for a second time, she remembered everything. And she asked me, as if it had been the day before, “You mentioned a movie, Wim. That’s an interesting idea.”

But that must have been a long time ago still. What held up production?

Yes, that was a good twenty years before we actually started the movie. It took us twenty years of talking. It had been my idea, but then Pina liked it more and more and finally was pushing for it. And that got me into the situation where I had to come up with how I would do it. And when I sat down and tried to figure out “How am I going to do this film with Pina?” I realized that I had no clue how to film dance – and especially how to film her kind of dance. And whenever I saw a new show of hers I felt the same lack of confidence. I didn’t know how to do it. I felt cameras were at a loss in front of a dance stage.

And I told Pina, “Whatever I imagine, it falls short. I feel like there’s an invisible wall between what I can do and what you do on stage.” And what I can put on the screen is just not the same excitement and the same intoxicating energy that I feel each time I see a live performance.

What is it about dance that’s difficult to translate? You’ve brought other arts to the screen: live music with Buena Vista Social Club or fashion with Notebook on Cities and Clothes. What makes Pina’s work so different?

Dance is a language all its own and it takes place in space and space is exactly what movies have never really been able to represent. Space is always fake – it is! In 110 years of cinema, it’s been fake. We try to do fantastic things with cameras. We throw them out of windows and we put them on planes and helicopters and cars, on rails and on cranes and do things that make the camera look very mobile (and the camera is very mobile), but the space? It always ends up on a two dimensional screen.

I realized that I couldn’t be in the same realm as the dancers. On film I always felt like I was looking into an aquarium and they are the fish. And I wanted to be in their element – I wanted to be in the water.

Pina understood because she had been involved in a couple of recordings of her work, so she knew that something didn’t really draw together between film and dance. She had experienced it herself. She said, “I know about that wall, but Wim, you’ll find a way to overcome it. Together, we’ll find a language for how to film dance.” And whenever she saw me, she’d say, “Do you know yet?” and I’d say, “Not yet, Pina.” And then we’d laugh. And after a while, she didn’t even ask me any more, she’d just raise an eyebrow and I’d shrug my shoulders and that would be the end of the conversation.

But it didn’t mean that we weren’t serious. I really would have dropped everything to do this film with her. But I was just at a loss for how to do it and I didn’t want to disappoint her. And that all ended when I realized that there was a new tool called 3-D.

(MORE: The Top 10 Movies of 2011)

What is it about 3-D?

For one, you’re in the dancers’ element and it’s no longer a fake space – there’s depth. But there’s something else: in 3-D, the body, for the first time, is round and has volume and is really physical and impressive. And dance – especially Pina’s dance — is so much about the language of the body. The bodies themselves tell us the entire story that Pina wants to tell us. I was thrilled to have a tool at my hands that really put a body in front of an audience. A body, not a surface. Because until then, in every dance, even in Singing in the Rain, Gene Kelly is a surface. I mean, he’s running around a lot and doing incredible things, but his body is flat.

And I felt that with 3-D, for the first time, the body could be round and voluptuous. And it’s something that I hadn’t really seen in 3-D films before, too. The first 3-D films really dealt with depth in space, but they didn’t deal with volume. You’d never see that in an action movie; a person doesn’t have volume. But 3-D has that capacity.

LIST: The All-TIME 100 Movies

What is dance theater and what makes it different?

Normally, actors don’t really dance and dancers don’t really act, so Pina needed her dancers to be great actors. She invented a form that was really neither ballet nor theater. Simply a new discovery that there was something else that you could do on stage, you just let the body speak its own language. And in a way where the audience could discover that they spoke that language. That’s what made me cry so much the first time I saw it and I didn’t know what was happening to me. I realized that my body understood that language on the stage – I spoke that language, I just didn’t know that I was knowledgeable. And the emotion that these dancers can create went straight into my bones and my bones knew what they were talking about.

And it’s not an aesthetic thing. Ballet is in many ways a very aesthetic experience, but dance theater is not at all. Pina didn’t really care about aesthetics. She said it herself: “I’m not interested in how my dancers move – I’m interested in what moves them.” And that is the entire difference right there.

(MORE: The Top 10 Plays and Musicals of 2011)

How much had you accomplished with Pina before her death? It sounds like you had to change the premise of the film significantly.

All the dancers you see are the dancers of the last couple of years of Pina’s company. Some of them have been with Pina since the beginning — for 20 or even 30 years. That was her company. And Pina decided only 4 pieces that we would record together for the film. And these four pieces had to be put on the agenda of the theater so we could film them, so they’d be rehearsed and everything.

But then she died before we could even start recording them. And the concept for the film we had written, which was a film about and with Pina, that concept was completely obsolete and that film could not be made any more. And I abandoned it. I announced to the crew and the production partners that there was no more movie. It was impossible to think of it. And that was the end of it for me. And I would have never reconsidered my position if it hadn’t been for the dancers.

How did the dancers convince you

It was only through these dancers that I was able to take the audience into the world of Pina Bausch. That they became Pina’s translators. As we couldn’t make the film with Pina anymore, and the only thing left for us to do was a film for Pina – all these dancers, together, took Pina’s part, so to speak.

They came to me two months after my decision to cancel and they said “Listen, we’re now starting to rehearse the pieces that the two of you chose together for your film and it could very well be that they’ll be performed for the last time. So we think, as we’re doing it now, we think you should do it too.”

And it made a lot of sense. They needed to do this movie – more than me. They needed to find a way to say their goodbyes to Pina because none of them could do that. Nobody had. None of her friends, family or dancers had been able to say goodbye. She’d disappeared from one day to the next. And I realized then that I wanted to say thank you and I wanted to say goodbye and I didn’t have an outlet. So I realized the movie was maybe more important for the living than as an homage to Pina and that convinced me we should make a movie – not the one we had planned, but we had to make another movie together.

Was there an effort to reconstruct her voice and use her vision as if she’d been involved? Or to shift the film so that it was more about the dancers?

Pina didn’t want any biography. She didn’t want this film to be about herself. From the very first time, 20 years ago when we first started talking about it until the very end when we wrote the concept for a 3-D film together, she didn’t want it to be about herself; about her childhood or how she learned to dance – she just wanted it to be about the work. I needed to respect that even as we were going ahead to make the film without her.

What would Pina think of the finished product?

Pina was so utterly critical with herself and with everybody. I don’t know. To tell you the truth, I had to ask myself that question each and every day. Because we really planned this together and I thought that I was going to do this with her standing next to me. So when I found myself setting up these scenes without her next to me, I looked over my shoulder and wondered to myself: “Is this good enough? Is this what I promised Pina?” And really asked her “Do you like it?” Because she was so close – I mean, for the dancers and for me. She was really present in a mighty way.

All the time, I thought of an audience, a person who did not know Pina’s work. I didn’t have an audience in mind that was dance literate. I thought it was great for people to see this film who were almost like me before I saw Pina – people who said “Dance is not for me, include me out.” For these people, I made the film.