![]()

This post is in partnership with Consequence of Sound, an online music publication devoted to the ever growing and always thriving worldwide music scene.

Throughout the 1970s, Alice Sheldon wrote stunning science fiction under the pseudonym James Tiptree, Jr.. Stories like “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” and “The Women Men Don’t See” dealt not only with aliens, but also with female alienation and gender politics, both in the present and the future. Sheldon explained the subterfuge in a 1983 profile with Asimov’s Science Fiction: “A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed.” In order to get the attention that her ideas deserved, she chose a man’s name, knowing that the fact that she was a woman would dominate the discussion or even be cause for dismissal outright. Decades later, Janelle Monáe is working some of these same topics of conversation into the world of pop music.

And while pop has produced a few artists clever and bold enough to break their eccentric, complex personas through in a major way, Monáe has given herself a sort of double challenge. She’s not only trying to get her decidedly specific, challenging ideas over in the easy-consuming mainstream, but she’s aligned herself with science fiction, a genre that, while tenfold more welcoming in popular culture than in Alice Sheldon’s day, still deals with many of the discriminatory, misogynistic, and homophobic issues that it did 40 years ago.

Monáe does adopt another persona to present her music, to be sure, but she’s adopting a more challenging persona (the rebel android Cindi Merryweather) rather than trying to sneak up to the table. Not only that, but the questioning of Monáe’s sexuality continues to be a rampant topic of discussion. Which is to say, she should by all accounts be painted into a tidy little corner, quite possibly an indie darling, rather than featured in nation-wide TV commercials.

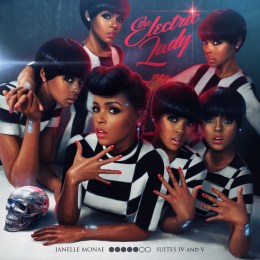

It’s a wonder, then, that Monáe continues to climb the pop ranks, not to mention with relatively little fanfare about the fact that she’s singing about androids. The Electric Lady comprises the fourth and fifth suites of her seven-part concept series, and rather than disorient the listener as they step into the depths of an intricately constructed world, she has managed to balance that narrative with what is perhaps her most pop step yet. Familiar faces like Prince and Erykah Badu cement her credentials without altering her course; Monáe has a strong enough voice to stand up to their legendary vocals.

It’s tempting to focus heavily on the influence of African American science fiction writers like Samuel Delany and Octavia Butler, particularly in the analysis of what it means to be “the other,” though Monáe is doing much more than rehashing. She’s expanding the discussion to new outlets, bringing her own personal sense of what it is to be the other to a larger audience, complete with funky rhythms and stellar pop hooks. The undeniable influences of Afrofuturism don’t stop with literature either: Monáe seems entirely aware of Funkadelic spaciness, Sun Ra mythology, and Afrika Bambaataa squiggly, robotic hip-hop, skipping from one influence to the next without aping any exclusively.

(PROFILE: Janelle Monáe in TIME)

That undeniable focus doesn’t come without its downside, though. For every smash funk single like “Q.U.E.E.N.” or the lush, soulful Miguel duet “Primetime”, there are a few too many clunky interstitials designed around the concept of a radio call-in show that drive the concept in with a hammer over the head and break the album’s flow — yet the music goes untouched.

The expansive epic “Sally Ride” combines Prince balladeering with elements of “Mustang Sally” into a dramatic song that bundles topics ranging from the first American female astronaut Sally Ride, to the fight against oppression, to something as blase the search for true love. “And I’m taking my shit and moving to the moon/ where there are no rules,” she richly croons, summing many of the album’s escapist fantasies and desire for a society where one can exist without needing to stay within preset boundaries.

On “Q.U.E.E.N.”, she hints at race, gender, religion, and sexuality in quick succession (“Am I a freak because I love watching Mary?/ Hey sister am I good enough for your heaven?/ Say will your God accept me in my black and white?”). “Dance Apocalyptic” is Monáe’s take at a “Hey Ya”-style pop throwback, matching André 3000′s full-throated swagger, knack for earworm brilliance, and embrace of dancing at all costs (“I really want to thank you for dancing til’ the end” may not carry the weight of “shake it like a Polaroid picture,” but then she’s talking about the apocalypse and zombies; Polaroid’s been out of business far too long).

At times, The Electric Lady suffers from some of the issues that plague many pop science fiction projects. Monáe’s distracting insistence to spell out some of the album’s fantastical aspects with heavy-handed elements wastes space and bloats the already lengthy runtime. As a result, it’s a very large world, but one stocked with charming character, tasty pop, and enlightening lyricism that shines like an electric heart through the android framework.

Essential Tracks: “Dance Apocalyptic”, “Q.U.E.E.N.”, and “Sally Ride”

More from Consequence of Sound: Listen to a full recording of Dave Chappelle’s comeback concert in Chicago

More from Consequence of Sound: Five Reasons Janelle Monáe Isn’t Your Average Sci-Fi Fan