![]()

This post is in partnership with Consequence of Sound, an online music publication devoted to the ever growing and always thriving worldwide music scene.

During Earl Sweatshirt’s time at a Samoan boarding school—and especially during the period of that time when the mythos surrounding him was at its most wildly imagined, before Complex divulged his location and the circumstances under which he was there—it was fun to imagine the already mythical young rapper would return to the States with not only diploma in hand, but also notebooks upon notebooks of raw, new material. Then, presumably, he would sift through the thousands of bars and promptly record the best of them, releasing a mixtape or two before joining back up with the rest of the Odd Future crew like he’d never been M.I.A. in the first place.

That was the ideal situation, anyway. As we had gathered from his eponymous single and his appearance on Odd Future’s “Orange Juice” cypher, here was a prodigiously talented MC—the best rapper in OF from a technical standpoint, though he didn’t possess the qualities that enabled Tyler, the Creator to ringlead the circus that is the Los Angeles collective—who hadn’t experienced much recognition for his music before being sent to an island in the middle of the Pacific by his mom, unhappy with her son’s academic performance and overall waywardness. Earl was 16 then, as yet unscathed by fame and the public’s overly optimistic expectations. Three years later, it’s time to vent a little.

(MORE: The Songs of Summer 2013)

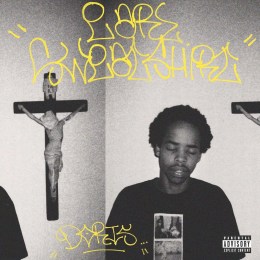

Lucky for us, he’s not doing so at the expense of anything that made him such a phenomenal prospect in the first place. On the Doris LP, Earl’s first release proper and first of any kind since his eponymous 2010 mixtape, half the fun is in his rapping: the indifferent yet slippery delivery, the curt clumps of consonance, the images that are joys to envision even if they seem to be assembled with no logical order. Just as important, though, are the human imperfections of the album, the instances when the supremely controlled Earl lets some healthy emotion seep through. It won’t affect the masses like Earl’s Odd Future cohort Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange did this time last year. Instead, it’s a work as notable for its technical achievements as its nuanced themes, and that’s almost as impressive considering that so many artists lack in one or both of those fields.

Goofy though it may be, the Doris line that stays lodged in my head is the one that opens the modestly spectral “Hive”: “Promise Heron I’ll put my fist up after I get my d*ck sucked.” You can tell by his tone that Earl realizes how ridiculous this might sound—he raps it with a smirk—but it’s a significant line in its juxtaposition of a firebrand like Gil Scott-Heron and the casual nihilism that the act of getting head can be. And if Doris is about one thing (which it isn’t, but let’s postulate), it’s Earl’s struggle to hang onto his youthfulness and his sense of self in light of others’ expectations. In that sense, Doris is similar to Mac Miller’s Watching Movies with the Sound Off, though I suspect that this one is closer to the album Miller wanted for himself.

“Sitting on the sofa feeling high and dormant.” “Too black for the white kids and too white for the blacks.” “Grandma’s passin’, but I’m too busy trying to get this f*ckin’ album cracking to see her.” It’s easy enough to discern the causes and effects of these statements, but the Earl of Doris appears to be in the throes of a particularly debilitating stupor, conflating beginnings and ends. “Chum” is the most personal cut here, and in it Earl falls just off meter as he crams in thoughts about the absence of his South African-residing poet father (“Honestly I miss this n*gga like when I was six / and every time I got the chance to say, I would swallow it”) as well as the immediate pressures he faced upon returning to America (“Been back a week and I already feel like calling it quits”). But Doris is not all reflection, as there are pleasures to be found in the odd simile (“Feeling as hard as Vince Carter’s knee cartilage is”) and Earl’s reluctant self-confidence (“Bars hotter than the blocks where we be at/ Stuntin’, these n*ggas gon’ flop like Dee-vack”). Plus, when he seems to pull fragments out of the air at random (“Desolate testaments trying to stay Jekyll-ish/ But most n*ggas Hyde and Brenda just stay pregnant”), all it takes is a few seconds to parse the lines and see just how much Earl can say in a relatively laconic couplet—though there’s no shame in consulting Rap Genius if you have to.

(MORE: A Conversation with Jimmy Buffett)

Again, Earl is a member of Odd Future, so it should come as no surprise that he gets by with a little help from his inner circle on Doris. OF affiliate Vince Staples is the only MC who truly keeps up with Earl here, his ominous verse on “Hive” even better than anything on his new Stolen Youth. Then there’s Domo Genesis, whose eternal fadedness aids closer “Knight,” a multi-suite stoner excursion that unfolds best in a playlist next to The Underachievers and Captain Murphy.

As for the production, about half of it was handled by Earl himself (operating under the dubious alias RandomBlackDude), the 45-minute LP a more musically interesting album than Channel Orange, even if nothing here has the radiance of “Pyramids”. Eschewing contemporary sounds like trap (save for the ticking hi-hats on “Uncle Al” and the deep bass on “Pre”), Doris is highlighted by The Neptunes’ contribution to “Burgundy,” a colossal shimmer of astral horns and insistent snares. Toronto trio BadBadNotGood’s “Hoarse,” on the other hand, is no conventional rap beat, but the heavily arranged outro is one of the moments where Doris is revealed to be a more subtly contoured listen than it ever had the right to be.

The single most meaningful collaboration here, however, is the Frank Ocean assist on “Sunday.” Earl sounds like he’s on the verge of tears as he addresses who we can presume to be his mom (“And I don’t know why we argue, and I just hope that you listen / And if I hurt you I’m sorry, the music makes me dismissive”), and Ocean’s quasi-rap alludes to the infamous Chris Brown incident from January (“I mean he called me a f*ggot, I was just calling his bluff/ I mean how anal am I gon’ be when I’m aiming my gun?”). The usual but decreasingly controversial Odd Future signifiers are at every turn on this album, but Earl’s place in the group’s hierarchy has never been more clear than it is on “Sunday,” a meditative song that the hardheaded Tyler couldn’t have made even if he already had Ocean’s verse or the organ-lined beat to work with. Tyler may be this group’s de facto leader, but Earl is the kind of guy—articulate, genial yet assertive, just a little vulnerable—we should want spearheading just about any youth movement.

Essential Tracks: “Burgundy”, “Hive”, and “Chum”

More from Consequence of Sound: Ty Segall Sleeper review