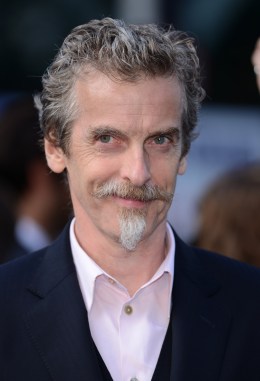

Peter Capaldi attends the World Premiere of 'World War Z' at The Empire Cinema in London, on June 2, 2013.

I’ve become fascinated, over the last week or so, at the reaction online to the announcement of Peter Capaldi as the Twelfth Doctor in Doctor Who. When his name was initially announced, during an admittedly-overblown, overlong television special designed to make the news “an event” that it really wasn’t, I’ll admit that the news surprised me. It wasn’t that I thought it was a bad choice — quite the contrary; Capaldi’s gift at playing irascible could be very welcome in the character. But the tendency in recent years has been towards younger, more heartthrob-y Doctors: Capaldi is a 55-year old former punk-rocker.

That said, what seems to be drawing so much online ire is just how expected a choice it was. While Capaldi may be the oldest Doctor since William Hartnell, the very first Doctor in 1963, he is —like the 11 before him—a white male. After all the speculation, excitement and rumor-mongering that, this time, we’d finally get a female Doctor or a black Doctor or some kind of Doctor that wasn’t just like all of the other Doctors that we’ve seen before, we ended up with one we’d expected all along. For a show in which the endless potential of people is such a recurring theme, Doctor Who can be very limiting at times in its casting choices.

Of course, the Internet wasn’t slow to be disappointed in the casting decision. Not in Capaldi as an individual — In fact, I suspect the grudging respect for Capaldi’s experience dulled a lot of the online disdain; I can only imagine what the reaction would have been like had the BBC chosen another attractive 20-something white male for the role to replace Matt Smith. But there was lack of nerve shown in choosing another white man for a role that could, in theory, be played by any actor on Earth with the right chops. The Who producers had, in effect, tried to play it safe only to discover that that was pretty much exactly what they were being condemned for.

Watching the response, I was reminded in an tangential way to the insane, appalling fallout that followed the Bank of England’s decision to put author Jane Austen on the ten pound note. For those who aren’t aware of this story, the BoE announced, in mid-July, that it was going to replace Charles Darwin as the face on the ten-pound note with Austen, celebrating one of the greatest — and most popular — writers the country had produced. You’d think that that would be something few would object to, but you would be entirely wrong. Opposition to the decision came from those finding fault with Austen’s never marrying, Austen being white and even the quote chosen to accompany the portrait on the note itself. As Slate’s Katie Roiphe put it, “the left, the right, the middle, the highbrow, the tabloidy, and the bloggy all found something to take issue with and object to.”

The fact is, there’s no safe choice anymore. The Internet’s ability to not only give voice to everyone with a web connection, but also — to an extent, at least — democratize the discussion by giving almost equal weight to all the voices participating has meant that, no matter what anyone may choose, for whatever reasons, someone will always be there to tell you that you’re wrong (and an idiot). For everything else, everything wonderful that the Internet can do, it has succeeded the greatest at being a machine that will tell you that Abraham Lincoln was only part right. Sure, you can please some of the people all of the time, but you really can’t please all of the people some of the time. Someone, somewhere, will always be so displeased with what you’ve done that they’ll tell you online (often accompanied by a “I don’t even care” disclaimer, even though they obviously care enough to spend the time to complain publicly).

This isn’t to complain about the Internet and the voice it provides everyone. Instead, it’s a suggestion to the moviemakers and TV makers and authors and artists and creative people of all stripes out there: Please consider this a license to go nuts. Seriously: If you’re going to have people criticize you no matter what you do, then why not do something worth criticizing? Look at the ubiquity of complaints as a reminder to stay true to your own instincts, and make the work you want to see. Everything else will follow — including, of course, the complaining.