The 2012 trial of Nechemya Weberman captivated New Yorkers: the prominent and respected counselor of the Satmar Hasidim sect stood accused of sexually abusing a young girl entrusted in his care. Incredibly, the youthful victim—who was 12 at the start of her four-year ordeal—and her family were ridiculed and defamed by many in this intensely insular ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, nestled in a Brooklyn neighborhood famous for its hipster clubs and cafes.

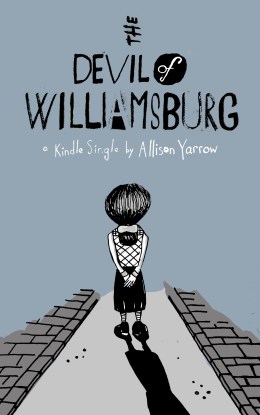

In her new Kindle ebook The Devil of Williamsburg, which goes on sale today, writer-editor Allison Yarrow offers a compelling account of a crime that horrified a city and forced a devout group of believers to confront some unpleasant truths. It is a piece of long-form investigative journalism—based on reporting, interviews, and courtroom testimony—that has as its narrative spine the story of two women: the young (and now married) victim and Weberman’s wife, who even now professes her husband’s innocence.

In the excerpt below, Yarrow likens the abuse suffered by the girl (called Rayna in the book, but whose real identity has been sealed by the court) to that of a victim of incest.

Not long ago, child sex abuse was a crime absent from American consciousness and conversation. Whether it took place in elite prep schools, collegiate sports, the Catholic Church, or in Hasidic Jewish enclaves, it was too unthinkable an atrocity to be given a language or a name.

Early awareness of and advocacy for the issue germinated in second-wave feminism. In a paper she gave at the New York Radical Feminists foundational conference on rape in 1971, social worker Florence Rush tore down Sigmund Freud’s assertion that children seduced adults. Adults were the culprits, she argued, as no child can consent to sex with a grownup, and abuse and incest were enabled by the composition and comfort of patriarchal family structure. Rush wrote The Best Kept Secret: Sexual Abuse of Children based on her paper, and while Kirkus Reviews derided it as “a tedious catalogue of unsavory sex,” it reshaped the conversation.

While Rayna’s abuse was not incest in the traditional sense, psychologist Lipner surmises that her experience shares territory with incest cases because of the tight-knit nature of the Satmar community.

“With incest in families, children are left with the difficult dilemma of wanting to hold the abuser accountable, protect themselves, and protect other people. If they betray their family member, they fear the family will break apart,” Lipner says. “The Satmar community is like extended family.”

The repeated rapes and abuses Rayna suffered bear an added layer of insidiousness common to victims who are abused by family members or close friends. As strange as it sounds, Rayna had loved her abuser in a way, and desired to protect him during the course of their four‐year relationship. That he preyed upon her innocence is only part of the story.

While away at Satmar camp one summer, Rayna wrote a love letter to Weberman. Sometimes he would drive up to camp to see her, but mostly their sessions were suspended during this time, and she missed the man who was a grounding force in her life. Lying on her stomach on a bunk in a dank cabin with her ankles crossed in the air, Rayna penned a missive.

“Dear Daddy,” it began in earnest. Rayna directed the wellspring of emotion into her pen, professing how much she loved and missed Weberman. She repeated an idea he had planted—that the two of them were spiritually bound. She professed, “We are one” and “I am you!” in bubbly handwriting, and waxed rhapsodic about their reunion at the summer’s end.

Rayna says Weberman was not only her abuser; he was also her confidant during the critical time in her life when she shed her girlhood. Coming from a home with relatively absent parents, Rayna hungered for adult attention and, for a time, trusted Weberman more than anyone. Exploiting a child’s trust is textbook predator behavior, as is assuming primary guardianship when parents are inattentive. By listening, opening his home to her, and fostering her trust, Weberman asserted himself as the most important adult in Rayna’s life. Her confusion is clear in the letter she sent him from camp in upstate New York.

“It wasn’t just touching,” she says. “We did discuss other things.” She shared with Weberman the details of her personal relationships and social life, her feelings about her status within the neighborhood and her school. She revealed to him her questions about God and her deep animosity toward Satmar and its rules. He was the first Satmar to hear her struggles without criticism, to validate them, and to talk through them with her. Weberman told a full courtroom he was trying “to save her life.”

There are multiple shades and layers in an abusive relationship between a predator and a child victim, says Lipner, who not only treats them, but was once one himself. He says some victims, especially boys, find physical pleasure in sexual encounters with their abuser, which is more distressing and confusing than abuse suffered alone. Despite complex feelings, “children have no mature capacity to consent to sex with adults, even if they like the adult, the attention, or the sexual touch,” Lipner stresses.

While Lipner does not believe Weberman’s abuse was sexually pleasurable to Rayna, he agrees that Rayna was exploited by someone who had earned her trust, and that it led to profound confusion, and her efforts to protect her abuser. The onset of Stockholm Syndrome in rape cases—when a victim identifies with the abuser—is “subconscious” and “involuntary” and can lead to “illogical concern for the abuser,” according to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network.

None of this nuance would do the prosecution any good in court, where narratives are delivered to juries in stark black and white. But it is a painful contradiction for victims. Rayna will forever wrestle with the shards of her relationship with Weberman.

In the meantime, Weberman’s legal team hopes to use the textbook confusion of the victim‐abuser relationship to Weberman’s advantage in their appeal.

.

Copyright © 2013 by Allison Yarrow

* * * * *

Allison Yarrow is a TIME contributing writer and a journalist living in Brooklyn. @aliyarrow