‘GONE WITH THE WIND’: A WOMAN’S WAR

Gone With the Wind is remembered as the love story of Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) and Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) — misremembered, really, since the object of Scarlett’s true and unrequited ardor is the prim aristocrat Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard). He is the idealized view of Southern gentility that so beguiles Scarlett, while moviegoers wait impatiently for her to get it on with Rhett. Her first husband, taken out of spite when Ashley rejects her affections, promptly dies in the War. Her second marriage, after the War, is simply a business decision, bringing her enough capital to rebuild her cherished homestead, Tara; her partner-husband also is quickly and conveniently killed. Still in love with Ashley, she marries Rhett — the “gentleman from Charleston, South Carolina” with, in Gable’s performance, a crisp Yankee accent and a sulfurous erotic insolence — not for his sex appeal, which was evident to every female in the movie audience, but for his money, which will restore her social standing and maintain her estate.

Indeed, Scarlett’s abiding beau — her constant lover and the spur to her ambition — is the land, Tara. Producer David O. Selznick’s film, no less than the Margaret Mitchell novel that spawned it, is really about real estate, the eternal obsession of warriors and homemakers alike. As the Confederate Army sacrificed tens of thousands of lives to defend its notion of sacred property, so Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler will do anything, anything, to hold on to Tara. At the end, deserted by Rhett, she is bereft but unbowed, because the land is hers to fight for till death.

(FIND: Gone With the Wind on the all-TIME 100 Movies list)

Less a war movie than a woman’s picture, GWTW takes the traditional female view of military conflict; it is concerned not with battlefield heroism but with the loss of all those precious young lives. The movie’s two largest scenes are of war’s destruction (the burning of Atlanta) and its aftermath (the sight of hundreds of wounded warriors). Men will fight, and women will weep. Ashley spends the whole war leading his regiment, or as the prisoner of the Yankees. Even the cynical Rhett joins the Rebel army, though not until the late summer of 1864, because, he says, he believes in lost causes only “when they are truly lost.” But the film stints on the men’s exploits and sticks with the women: Scarlett, Ashley’s demure bride Melanie (Olivia De Havilland) and the Tara house servants Mammy (Hattie McDaniel) and Prissy (Butterfly McQueen).

While she fights to survive, Scarlett mourns her fallen friends and relatives, the tragic deaths of her own two children and, finally, the end of her cherished way of life — the Confederacy. In portraying one of the strongest women in film history, this ultimate Hollywood movie also plays a requiem for a rich and tainted civilization that is, in the poet Ernest Dowson’s words, “gone with the wind.”

GENERAL KEATON

“I think it’s the Civil War movie,” Orson Welles said of The General in 1971. “Nothing ever came near it, not only for beauty but for a curious feeling of authenticity… Nobody except Keaton has brought us that close to the feel of the Civil War… It’s a hundred times more stunning visually than Gone With the Wind.”

Unlike Selznick’s epic, and Griffith’s, The General was based on an actual war incident: the “great locomotive chase.” On April 12, 1862, James J. Andrews, a civilian spy for the Union, and seven of his allies hijacked a Western & Atlantic railroad train, the General, in Big Shanty, Ga.; they jettisoned most of the passenger cars and drove the locomotive north toward Chattanooga, Tenn., disrupting important Confederate supply lines. The train’s conductor, William A. Fuller, pursued the General first on a handcar and then by commandeering another locomotive. When the General ran out of fuel, Andrews abandoned it 18 miles from his destination. All the raiders were captured, and Andrews was hanged that June. Most of his abettors escaped, and were the first men ever to be awarded the Medal of Honor; Secretary of War Edwin Stanton did the honors. (In Spielberg’s Lincoln, Stanton, played by Bruce McGill, is the one who complains to the chatty President that “I can’t stand to hear another one of your stories!”)

(READ: Keaton the Magnificent)

This true caper served as inspiration for a 1911 one-reel film, Sidney Olcott’s Railroad Raiders of ’62, and for the 1956 Disney feature The Great Locomotive Chase, starring Fess Parker (TV’s Davy Crockett) as Andrews and Jeffrey Hunter as Fuller. The Disney version is told from the North’s point of view, trumpeting the scheme’s brazen ingenuity, as if it were a 19th-century Argo. The General, which Keaton co-wrote and co-directed with Clyde Bruckman, puts its sympathies on the South’s side. Its “Captain Anderson” (Glen Cavender) is the thief; the Fuller character — Keaton’s Johnny Gray, here not the conductor but the engineer — pursues the kidnappers to reclaim the train he loves. Oh, he has a girl, with the Edgar Allan Poetic name of Annabelle Lee (Marion Mack), who is also in the Yankees’ clutches. Yet when he rescues her, she nearly loses the Civil War three years early. Exasperated by her “helpfulness” trying to stoke the locomotive engine, Johnny impulsively throttles her, then kisses her, then returns to the job at hand.

Beginning with Johnny’s rebuff at enlisting in the Confederate Army (he’s told his skills are needed instead as engineer) and climaxing with a battle in which he almost inadvertently conquers the Northern foe, The General devotes nearly an hour of its 79-min. running time to the chase — a marvel of story construction and sight gags from the most inventive comedian in movie history. Watch Keaton’s beautiful, compact body as it pirouettes or pretzels in tortured permutations or, even more elegantly, stands in repose as everything goes crazy around it. Watch his mind as it contemplates a hostile universe whose violent whims Buster understands, withstands and, miraculously, tames. And please, amateur historians as well as movie lovers, make a date to watch The General. It’s the one long-ago Civil War film that can be enjoyed with no apologies or footnotes, its thrills forever fresh, its moviemaking joy intact.

THE BIRTH OF WHAT NATION?

Nearly a century after it was made, The Birth of a Nation stands as a monument to cinema’s power both to use the medium to tell a complex story, in grand images the world could understand, and to shape and distort public opinion. The son of a Colonel in the Army of the Confederacy, Griffith based his epic on Thomas Dixon’s popular novel and play The Clansman. That was the film’s title at its world premiere in Los Angeles, before the opening a month later in New York City (at a top price of $2, when tickets to most movies cost a dime). Produced for $100,000, Birth was estimated to have earned $18 million in its first few years — the astounding equivalent of $1.8 billion today. In current dollars, only Avatar and Titanic have earned more worldwide.

Griffith took this monumental risk without a real script, and using just one camera manned by his invaluable cinematographer, G.W. “Billy” Bitzer. At heart a Romeo-and-Juliet story extended to gargantuan proportions, the movie focuses on two families, the Northern Stonemans and the Southern Camerons, whose eldest sons fall in love with girls from the other clan. Though the Civil War places the young men on opposing sides, they retain respect for their old friends — Ben Stoneman (Henry B. Walthall) stops mid-battle to comfort a wounded Cameron — and love for their ladies. It is romantic chivalry, Griffith insists, that led to Southerners’ night rides against Negroes. A rapacious black man stalks a young white woman until, to protect her virginity, she leaps off a cliff to her death. To avenge such indignities and defend the honor of white womanhood, Ben and his noble fellows give birth to the Ku Klux Klan. That, not the restored United States, is the Nation of the film’s title: the land of lynchings, voter suppression and second-class citizenship for Southern blacks.

(READ: TIME’s 1948 obit on D.W. Griffith by subscribing to TIME)

Basing August Stoneman on Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones in the Spielberg film), Griffith turned the character, as played by Ralph Lewis, into a zealot who is dominated by his shifty mulatto housekeeper-mistress, and who imposes humiliation on the white South in the name of Reconstruction. Negroes in the movie (usually white actors in corkface) are subhuman oafs or savages. So vile was the caricature of blacks, so rousing the Klan’s midnight ride to the Old South’s idea of justice and so persuasive Griffith’s storytelling through pictures that the NAACP demanded suppression of the film — and the modern Klan was born.

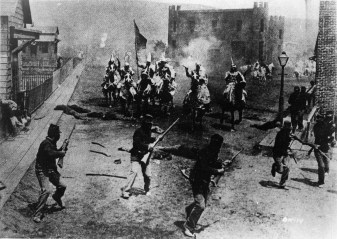

Yet The Birth of a Nation is nearly as antiwar as it is antiblack. The Civil War scenes, which consume only 30 minutes of the 3hr.13min. extravaganza, emphasize not the national glory but the human cost of combat. “On the battlefield,” announces one of the film’s intertitles, “War claims its bitter, useless sacrifice.” For all the spectacular panoramas of the battle footage, its explosions and ragged processions of soldiers, the most impressive and startling moments are the more intimate views of the battle’s end. “War’s peace,” reads another intertitle, and we are shown a tableau of a half-dozen dead soldiers, as if taking a restorative rest after their fatal labor. These images have the impact of defiant art: Goya’s Disasters of War or Picasso’s Guernica. Griffith may have been a racist politically, but his refusal to find uplift in the South’s war against the Union — and, implicitly, any war at all — reveals him as a cinematic humanist.

‘ADRIFT IN A SEA OF BLOOD’

War’s price was evident to the Generals on the hill, every bit as much as to their cannon fodder below. In the 1993 Gettysburg film, Robert E. Lee muses that “this war goes on and on, and the men die, and the price gets even higher. We are prepared to lose some of us, but we are never prepared to lose all of us. We are adrift here in a sea of blood and I want it to end. I want this to be the final battle.”

Gettysburg was the bloodiest but not the final battle of the Civil War; hostilities would drag on, and casualties multiply, for another 21 months. No Audie Murphy emerged from it with hundreds of clean kills and a hero’s luster. It was an exercise in organized slaughter. And that may explain why this crucial event has inspired so few movies.

(*CORRECTIONS: The original text stated that 50,000 soldiers were killed in the battle; we also mistakenly identified James Longstreet as a Union general)

To mark the 150th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg, TIME has published a richly illustrated 192-page book, Gettysburg: Turning Point of the Civil War. To buy a copy, go to time.com/gettysburgbook