It’s not surprising that Frieda Hughes, 53, is given to dramatic gestures. Being born the daughter of poets Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes is to be thrust into that role. Plath, the author of the celebrated novel The Bell Jar, killed herself (by sticking her head in an oven in her London flat) on February 11, 1963 — this year marks the fiftieth anniversary — after Hughes left her for another woman. Frieda and her brother Nicholas were sleeping in the next room.

Before he died in 1998, Hughes, who became the poet laureate of England, gave Frieda and Nicholas more than 40 drawings by Plath. When Nicholas took his own life in 2009 at his home in Fairbank, Alaska, Frieda became the sole owner of her mother’s artwork. It was announced last week that those drawings would be collected in a book, edited by Frieda, and to be published by Faber and Faber in England (on shelves this September), and by HarperCollins in the U.S. (November).

The pictures were drawn during the happy early days of the couple’s life together, immediately following their June 1956 marriage; Plath drew many of them on their honeymoon in Paris and Benidorm, Spain. But don’t expect an exhibition of the artwork to accompany publication. Frieda told TIME on the phone from her home in Wales that she sold all but one of the pen-and-ink drawings two years ago, at their first public showing at London’s Mayor Gallery. From that entire trove of her mother’s drawings, she kept but one for herself: a portrait of her father.

Why would she sell all of her mother’s artwork? “It was a decision I didn’t come to easily, but I’d had an awfully long time to come to that decision,” said Frieda. “People start shedding as they get older. There’s always been a joke—well, it’s not so much a joke—people have always said, “Along when you hit 50, you start getting rid of things. There is a certain truth about that. Also, I didn’t have children. If I had, to be honest, I probably would have hung onto them and left them for the children. So there are certain aspects of being without family that we consider in a different way.”

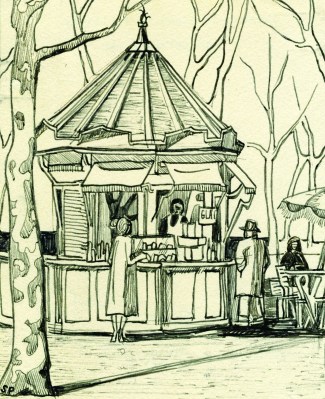

The artwork in question was well documented. Frieda’s parents, pioneers of confessional poetry, chronicled their every move, and the creation of these pen-and-ink drawings were no exception, Plath wrote joyfully to her mother on August 25, 1956 about the art she did during her honeymoon in Spain:

“Wait till you see these few of Benidorm—the best I’ve ever done in my life, very heavy stylized shading and lines; very difficult subjects, too…I feel I’m developing a kind of primitive style of my own which I am very fond of. Wait till you see. The Cambridge sketch was nothing compared to these. Ted wants me to do more and more…”

Likewise, Ted Hughes wrote about the honeymoon sketches in 1998, near the end of his life, in Birthday Letters, a bestselling book of poems about his tumultuous years with Plath:

“Drawing calmed you. Your poker infernal pen

Was like a branding iron. Objects

Suffered into their new presence, tortured

Into final position. As you drew

I felt released, calm. Time opened

When you drew the market at Benidorm.

I sat near you, scribbling something.

Hours burned away. The stall-keepers

Kept coming to see you had them properly.

We sat on those steps in our rope-soles,

And were happy…”

—“Drawing”

While Plath is best known for her triumphantly dark “Ariel” poetry at the end of her life, most of her fans would be surprised to learn that she came close to pursuing a career in art. She wasn’t sure until she was 20 years old whether she was going to be an artist or a writer. Pastels, pencils, pen and ink, oils, charcoals, collages: “she did it all. She was a visual artist from Day One,” says Kathleen Connors, editor of Eye Rhymes: Sylvia Plath’s Art of the Visual (2007). But Plath ultimately chose to dedicate herself to writing, a path that would make her one of the greatest poets of the last century.

When the pictures that will appear in the book were finally shown in public at her 2011 London show, British critics were all over the map in their judgments. As with every other detail in Plath’s life, they were psychoanalyzed and dissected.

The Independent was blunt:

“What we really want to know about this exhibition is this: how does it connect with the rest of her tragic life? Are these drawings pent, febrile and tortured in the way that many of the poems are pent, febrile and tortured?

“No. For the most part they show us a young woman who is serious about her art, but they don’t reveal the dark underbelly of it all that the poems reveal. If anything, most of these works are polite and as well brought up as Plath herself was well brought up.”

The Economist was unimpressed:

“Seen in the shadow of the poetry, the drawings seem empty. They are cold, cartoonish attempts to escape the inner torment that her poetry described…we hear a soft, private whisper, perhaps even a girlish giggle. This is Sylvia Plath at her most unbearably light.”

But the same day, the Guardian came to a totally different conclusion:

“I found these drawings moving: not because they feed into the legend, but because they sidestep it. They bring us a fresh look at a woman now so barnacled with myth it’s hard to see her clearly. And—wow—they’re really good…Now cast an eye over these wonderful drawings. You wouldn’t connect them with that poetry at all. And you wouldn’t connect the, either, with the prose Plath, the psychotic bobbysoxer of The Bell Jar. With these drawings, we get a third Sylvia Plath.”

One of Plath’s biographers, Andrew Wilson, author of Mad Girl’s Love Song (2013) is not surprised by the divergent reactions. “I think it’s one of the things that critics do find hard to deal with, because they often want artists to be all of a kind,” Wilson told TIME. “They would have obviously probably liked Sylvia Plath to be drawing scenes of devastation and death and misery.”

* * * * *

Frieda, a talented painter and published poet herself, says she grew up largely unaware of her mother’s obvious talents as a visual artist.

“For years I really wasn’t conscious of my mother’s drawing, until my father actually gave them to us,” she said. “Because although he said that my mother drew, my father would sit down and sketch and things would grow out the ends of his fingers onto the page, and he was just the most superb natural sketcher and drawer. So I used to assume that my love of painting or my desire to paint, if it’s genetic, then perhaps I got it from him, and he’d say, no, no, no, no, from your mother, from your mother.”

Frieda’s own artwork has been shaped by rocky times in her life. She says of her current work, “I’ve got this series of paintings called ‘The Transition Series,’ some of which have already sold. I am painting the wasteland my life appeared to be after the death of my brother, [my] divorce, which was rather painful after 13 years of marriage, also, because I seem to be without any close family, and trying to construct a more positive and happy and beautiful and attractive landscape. I’m very careful what I’m putting in.”

Despite her role as the editor of the forthcoming book, Frieda rarely seeks the spotlight. She has lived in Wales for nine years, 200 miles from London. Although the anniversary of her mother’s death was much remarked upon in literary circles, Frieda, for the most part, has kept a low profile, emerging briefly this month to arrange a reading of her mother’s poetry at the British Library. “I live really quietly,” she explained. “I don’t spend much time on a computer. Literally, I only check my emails once, occasionally twice a day…It’s a gift, because I get so much more done. And also, it’s sometimes a good thing just to be, well, a bit out of the way.”