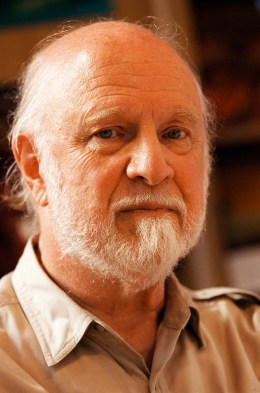

Richard Matheson in Saint-Malo, France, on May 7, 2000

Fear lives forever. If as kids we are scared witless by some moment in a story, movie or TV show, it goes into a bank of memories we can tap and withdraw, with a shudder or a smile, for the rest of our lives. In popular culture of the past 60 years, few writers deposited more images of dread in the cultural consciousness than Richard Matheson, who died Sunday June 23 at his Calabasas, Cal., home at the age of 87. Here are a few of the images he implanted:

A man notices he is losing wright — no, he’s getting smaller (The Incredible Shrinking Man). An airline passenger sees a gremlin cavorting maliciously on an airplane wing (“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” on The Twilight Zone). A driver on a lonesome highway is menaced by a killer truck (“Duel,” made into a 1971 TV movie by Steven Spielberg). A child disappears into the fourth dimension, her cries still audible to her father (“Little Girl Lost,” The Twilight Zone). A plague of vampires roams the Earth (the novel I Am Legend). A man discovers he has psychic powers that make him hear the thoughts of his neighbors, and of the restless dead (A Stir of Echoes). A young couple is visited by a stranger who tells them they’ll be rich if they just push a button that will instantly kill someone they don’t know (“Button, Button,” The Twilight Zone). A woman buys a Zuni fetish doll as a joke gift, then is attacked and assaulted when the doll comes to life (“Prey,” later a segment in the TV movie Trilogy of Terror).

Any of those ring a bell in the pit of your gut?

(READ: TIME’s 1954 review of the Richard Matheson novel I Am Legend)

A prodigious dreamer-upper of macabre twists on everyday life, Matheson wrote 28 novels, 88 short stories and dozens of movie and TV scripts (for Star Trek, The Alfred Hitchcock Hour and Night Gallery, among many others); he is as important in film history as he is in fantasy literature. He either turned his own novels into movies — the 1971 Hell House, filmed in 1973 as The Legend of Hell House — or adapted the work of others. He spun the fiction of Edgar Allan Poe into four excellent films (House of Usher, Pit and the Pendulum, The Raven and Tales of Terror) for director Roger Corman and star Vincent Price. He adapted Jeff Rice’s unpublished novel about a vampire serial killer into the 1972 The Night Stalker, the highest-rated TV movie of its time.

And when he got tired of being pegged as a specialist in horror (a term he hated), the novelist wandered into wonder and created two “supernormal” love stories. The 1975 Bid Time Return, filmed as Somewhere in Time, transports a dying writer into the romantic past to meet a woman he had seen in a photograph. (Her startling first words, when they finally meet: “Is it you?”) In the 1978 What Dreams May Come, a man who has died and gone to Heaven retrieves his beloved wife from Hell, like Orpheus saving Eurydice. “Somewhere in Time is the story of a love which transcends time,” Matheson later said. “What Dreams My Come is the story of a love which transcends death. I feel that they represent the best writing I have done in the novel form.”

(READ: Bruce Handy’s take on the movie made from What Dreams May Come)

Born in Allendale, N.J., in 1926, Richard Burton Matheson grew up in Brooklyn, the son of Norwegian immigrants. In the introduction to the 1989 edition of his collected stories, he wrote that his mother Fanny was “An orphan before she was 10, raised by an older brother. Insecure and frightened, thrust into an alien environment.” Of his father Bertolf, a tile installer, Matheson recalled: “Refuge from this alien world was sought in alcohol which served to blunt the nerve ends and numb away the fears and anxieties.” The boy’s life seems a vignette from an Ibsen play, with seething repressions and exploding rages. “Existing in this cloistered family world, the outside world representing a threat to me, I found personal escape in writing. Instead of imbibing drink, I imbibed stories: became addicted to fiction. Instead of turning to religion, I turned to fantasy.”

After graduating from Brooklyn Tech in 1943, he spent the war in the infantry and got a journalism degree at the University of Missouri. By the early ’50s he had moved to Los Angeles, married Ruth Ann Woodson (they would have four children, three of them writers) and befriended other L.A.-based fantasy writers, including Ray Bradbury, Charles Beaumont, William F. Nolan and Jerry Sohl.

(READ: Lev Grossman’s tribute to Ray Bradbury)

Matheson’s familiar method, and true genius, came from transforming the ordinary into the bizarre, the terrifying into the indelible. His method: “Take a simple, real situation, then tweak it a little.” For example, parents coping with a “difficult” child. “What would happen if a normal couple had a monster for a child?” That was the inspiration for his first published story, “Born of Man and Women,” written when he was 22. The second inspiration: narrating it in broken English from the point of view of the monster child, thus building empathy for a creature who is chained in the basement and beaten by its father, but who thinks and feels like a sad, all-too-human eight-year-old. Published in 1950 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, “Born of Man and Woman” immediately established Matheson’s name in the burgeoning postwar fantasy genre.

Story ideas came from everywhere, including movies. As a kid in Brooklyn, Matheson saw a revival of the 1931 Bela Lugosi Dracula. Even then, he later said, “the thought occurred to me: If one vampire is scary, what if the whole world were full of vampires?” Hence the 1954 novel I Am Legend, which inspired George Romero to turn vampires into zombies for his 1968 Night of the Living Dead. It also birthed three big movie versions, the last one (in 2007) starring Will Smith, and none of them observing the niceties and spectral power of Matheson’s story. (“I don’t ever expect to see it done [faithfully],” he said.) But the novel still lives on book shelves and shivers in readers’ memories.

(READ: Corliss’s review of the Will Smith I Am Legend)

All right, multiply the undead — easy enough, in retrospect, even if no one had thought of it before. But how about noticing the tiniest vignette from a minor romantic comedy and turning it into a meditation on man’s diminished significance in the Atomic Age? In the 1953 movie Let’s Do It Again, Ray Milland leaves Aldo Ray’s apartment and, having taken Ray’s hat instead of his own, finds it much too big. Seeing this, Matheson asked himself, “What if a man put on his own hat and it was too big?” He developed that line of inquiry into the story of an ordinary fellow who gets smaller and smaller, nearly infinitesimal. That was his 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, which a year later Matheson adapted into the SF movie classic The Incredible Shrinking Man.

An ordinary life triggered extraordinary stories. The notion for Somewhere in Time originated in a visit to Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City, Nevada, where Matheson saw a photo of Maude Adams, the enchanting Broadway actress of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “It was such a great photograph,” he said, “that creatively I fell in love with her. What if some guy did the same thing and could go back in time?” In the early ’50s, in his family’s Venice, Cal., apartment, Matheson was wakened by the cries of his his young daughter Tina. When he went into her room he couldn’t find the child until he saw she had rolled under her bed all the way to the wall. “All I had to do was add the fourth dimension,” and presto, “Little Girl Lost,” later a Twilight Zone episode — and the prototype for the Spielberg-produced Poltergeist.

(FIND: The Twilight Zone on James Poniewozik’s list of the all-TIME 100 TV Shows)

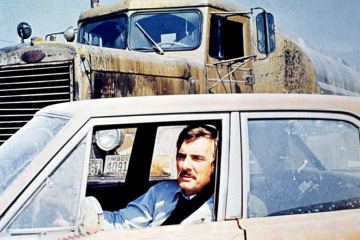

On Nov. 22, 1963, Matheson was playing golf with Sohl when they learned President Kennedy had died. On the way home, their car was tailgated and sideswiped by a huge truck that drove them off the road. A few years later, he embellished the adventure as “Duel.” The TV-movie version provided the 24-year-old Spielberg with his feature directing debut. “It’s Psycho and The Birds, on wheels,” said Spielberg in a 2004 interview for the Duel DVD. The psycho is the unseen truck-driver playing cat-and-mouse with the solitary driver (Dennis Weaver) whom Matheson unsubtly called Mann, as in Mann vs Machine. The Birds aspect: the inexplicable made inescapable. “And to give credit where credit is due,” Spielberg added, “it was Richard Matheson who was very clear in his teleplay that you didn’t see the driver. That attracted me more than anything else. The unseen is always more frightening than what you throw in the audience’s face.”

Spielberg’s view was Matheson’s. “I hate the word horror,” the author told fantasy editor and writer Stanley Wiater for the 2009 video doc Dark Dreamers. “To me, the word horror is visceral. Terror hits you in the mind. You don’t have to show anything to scare a lot of people.” Just the wail of an invisible child, or the face of a furry gremlin (played by Burt Lancaster’s pal and stuntman Nick Cravat) on the wing of a Twilight Zone plane.

(READ: Corliss’s review of Twilight Zone: The Movie)

Matheson wrote 14 Twilight Zone episodes under the genial aegis of Rod Serling. His initial pitch to the host-creator: “A World War I pilot gets lost in a fog and lands at a modern SAC base. And he said, ‘Oh, go home and write it!'” That became “The Last Flight” in the show’s first season. Serling respected his fellow writer; Matheson says that in the process from page to screen, “I don’t recall one word ever being changed.” And as he branched into movie writing, he found that producers — who thought “scriptwriters were scum” — seemed awed that he was a working novelist and were less likely to tamper with his screenplays. “I’ve always been glad that I kept writing prose, because if I had just gone into writing scripts entirely, by now I would have died from a broken heart.”

As he cruised into his 80s, he found Hollywood producers still eager to take his old stories and “improve” the essence out of them, as with the 2007 I Am Legend and the 2011 Hugh Jackman drama Real Steel, which was much too loosely based on Matheson’s 1956 story and 1964 Twilight Zone teleplay “Steel.” He also kept receiving awards from literary groups. Last year the Horror Writers Association named I Am Legend the Vampire Novel of the Century — “a dubious but interesting distinction,” the honoree noted. (Matheson died just three days before he was to receive the Visionary award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Films.)

(READ: Mary Pols’ review of Real Steel)

And he kept spinning his own life into the most curious fiction. He based the particulars of the dead man’s loved ones in What Dreams May Come on his own family. And in the 2012 autobiographical novel Generations, he restages his father’s 1957 funeral, which evolves into a catharsis of family scab-lifting and soul-bearing. “The strangeness of this account is that it never happened,” he wrote. “It could have happened. For that matter, it should have happened.”

In Matheson’s real life, people often told him of the effect his fiction had on them. Stephen King has said he was spurred to a career as a writer by reading The Shrinking Man and Matheson’s Twilight Zone stories. Matheson said he couldn’t go to a Hollywood meeting without middle-aged executives telling him that, when they saw the Zuni doll episode of Trilogy of Terror as kids, they wet their pants. More meaningful were the responses of those who had read What Dreams May Come. “A person would write to me,” he noted in Dark Dreamers, “and say, ‘My mother is dying. And she was terrified of the whole idea of dying. And she read your book and she’s in perfect peace now.’ And I think, ‘Oh, that’s it!’ You can’t do any better as a writer.”

(READ: Stephen King on learning from Richard Matheson)

He couldn’t do better. Nobody could. Richard Matheson leaves behind his loving children — Tina called him “the best father in the world” — and an immortal legacy of chills. Poor kids today: they may have to find their own touchstones for terror. Or they could just watch old Matheson movies. A couple of summers ago, two nine-year-olds, Stella and Dunham Stewart, were treated to the sight of the Zuni doll chasing Karen Black with his tiny, toxic spear. The old black magic worked: they too were scared witless.

For the next generation of kids to be touched by Richard Matheson’s stories, what nightmares await! What dreams may come!