To celebrate the beginning of a new season, TIME editors have compiled a list of our favorite summer reads from the past 40 years. What defines a summer read? To us, it’s the kind of buzzed-about book that seems to flourish in warmer months, equally ubiquitous on beaches and in subway cars. (Not all summer reads are mindless page-turners—one of our selected titles is a brainy mystery that touches on medieval studies and semiotics.) Once you’ve perused the list, take our poll and help us crown the All-Time, Ultimate Summer Read.

And we acknowledge that our list is by no means definitive—though we think it’s a darn good representation of 40 years of seasonal tomes. So we invite you to help fill in our gaps—to correct what you might think are our egregious oversights—by telling us which books should join our list. Tweet your picks—or share what you plan on reading this summer—using the hashtag #SummerBooks. We’ll post the winner of this poll alongside a collection of your suggestions next Friday, June 27.

And now, on to our list…

Love Story, Erich Segal (1970) After leaving Harvard with a PhD in Comparative Literature, Segal published this fictional account of a Harvard-Radcliffe romance. The same year, the book was made into what would be one of the biggest films of the decade, starring Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw. Both the novel and the film became cult classics, known for their sappy tagline “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” Love Story was published in February 1970, and reached #1 on the New York Times’ Best Sellers list in May. Success meant Segal never had to say he was sorry.

The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty (1971) Blatty’s fifth novel told the story of a Washington D.C. girl whose mother seeks out a local priest to treat her demon-like behavior. Based on an urban legend Blatty heard more than 20 years earlier in college, the novel was part of a wave of cultural preoccupation with demonic possession (think: Rosemary’s Baby). Blatty also wrote the screenplay for the film version, which came out two years later and featured a demon girl projectile-vomiting pea soup onto a priest’s face, and scared-to-death baby boomers leaving the theater. The novel stayed at #1 for most of the summer of ’71, and the adapted screenplay earned Blatty an Oscar.

Jaws, Peter Benchley (1974) The film adaptation’s most famous line—“You’re gonna need a bigger boat”—appeared nowhere in the original novel. But the book was a massive success, and paperback versions could be seen on display in every bookstore in the summer of ‘74. The story of a small beach-town ambushed by a shark with a taste for human flesh stayed on the bestsellers list for almost a year, and offered avid readers a good excuse to stay out of the water during trips to the beach.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, John le Carré (1974) Le Carré’s seventh novel stars his most famous recurring character, George Smiley (later played by Alec Guinness in the 1979 BBC television series), an intelligence officer called back into duty in order to track down the Soviet spy who infiltrated England’s Secret Intelligence Service. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, was one of le Carré’s favorite of his own books (along with The Spy Who Came in from the Cold); published in June, it provided a handy Cold War distraction for all the readers too scared by Jaws to go near the ocean.

The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco (1983*) In his first novel, semiotician–turned–thriller-writer Umberto Eco laid a Sherlock Holmes trope over a story about murders in a Benedictine monastery: in a nod to Conan Doyle the friar sent to investigate (Sean Connery, in the film, accompanied by his Watson-like sidekick Christian Slater) is named William of Baskerville and concludes at one point that a deduction was “elementary.” It turns out that the murders actually tie in to a plot attempting to hide a lost chapter of Aristotle’s Poetics—which, to be fair, any learned person would in fact probably murder to get their hands on. Somehow, this all braininess translated into a hot beach read. (*The book was originally published in Italian in 1980, and translated into English in 1983)

(MORE: Season’s Readings: Best Summer Books 2012)

American Psycho, Bret Easton Ellis (1991) Ellis’s central character, Patrick Bateman, sells junk bonds, lives in a Central Park West penthouse and eats at the city’s finest restaurants; but when he leaves the office he indulges an insatiable compulsion to kill. In addition to being a serial killer, Bateman is also a proto-metrosexual: he obsesses over mineral water, and spends a page and a half describing his morning skincare routine, down to which eye cream he prefers. Although it never made any bestsellers list, the publicity surrounding the book’s original publisher dropping the title made American Psycho the macabre fascination of the year.

The Pelican Brief, John Grisham (1992) Grisham’s third novel (and one of his most famous), The Pelican Brief begins with the murder of two Supreme Court Justices and follows the detailed amateur investigation of a law student and a reporter. The novel marks an interesting shift in mystery thrillers: no longer were the main characters Smith & Wesson-toting private eyes, but rather, journalists chasing a story bigger than they can swallow.

The Celestine Prophecy, James Redfield (1993) Perhaps the most interesting thing about Redfield’s runaway best-seller is that it was actually a successful self-published book, back when self-publishing required a lot of start-up money and dead trees. The author sold almost 100,000 copies—many from the trunk of his car—before it was picked up by Warner Books. The story focuses on spiritual phenomena and an ancient Peruvian text that illustrates key enlightening and spiritual moments humans should undergo. The narrator travels to Peru to experience these nine spiritual insights. Because the book sold so well, the author decided to write another one about a tenth insight, but that one attained neither beach-read nor cult status.

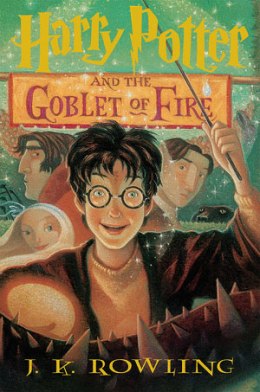

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, J.K. Rowling (2000) The fourth book in the blockbuster series about the boy wizard was the first volume released simultaneously in the United Kingdom and the United States. It was also the first time a Harry Potter release was met with fans in Harry and Hermione costumes waiting in line at midnight—that is, until the first Harry Potter movie came out a year later.

The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown (2003) Academics were surprised when they learned, a few pages in, that The Da Vinci Code was novel about the secret life of Jesus, instead of a text about Da Vinci. But then, Dan Brown wasn’t writing for academics. His breathless tale, which earned criticism for misrepresenting various schools of thought on art and religion, sold more than 50 million copies and was made into hit movie in which Tom Hanks regularly mispronounces “Knights Templar.” The Da Vinci Code was on the New York Times best sellers list for more than 150 weeks—about three years.

The Girl Who Played With Fire, Stieg Larsson (2009) In France, Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series—with its unlikely crime-solving duo of a financial journalist and a misanthropic hacker—was the trendiest trilogy to carry around in the Metro. When the posthumous series finally hit the US, the books sold so well that they went to paperback while the hardcovers were still on shelves in some bookstores. The Girl Who Played With Fire—the second installment in the series—became the book to read during the summer of 2009, and made it to #1 on the Times list in August.

Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn (2012) A journalist moves his wife from New York to the small town he grew up in and becomes the lead suspect when she mysteriously disappears. At first one might assume that, like The Shining, Gone Girl is a polemic against marrying writers and removing them from big cities. Later, however, it becomes clear that Flynn’s breakout novel is less a thriller about a disappearance than a study of a marriage fraught with problems and deceit that has manifested itself by way of a thriller. Either way, if you weren’t reading it last summer, you missed the definitive book of the season.

[polldaddy poll=”7192699″]