In the last fifteen years, the ambitious TV drama has evolved, well, dramatically. Going back decades, the standard format, with few exceptions, was to tell distinct, individual stories–police investigations, court cases, &c–that wrapped up in an hour and generally had clear, unambiguous rooting interests.

Many dramas still do that (CBS’ cop shows, for instance) but beginning in the late ’90s a string of shows expanded the form–by introducing complex narratives and antiheroes, and by using the structure of series TV to tell much, much longer stories. Some, like Treme, are essentially extended novels, with not much to mark the beginning and end of an hour other than the titles and the credits. Others, like The Good Wife, combine discrete hourlong stories with much longer arcs. By using what makes TV different from the movies, they use the medium to tell stories that go on and on until they end, like life.

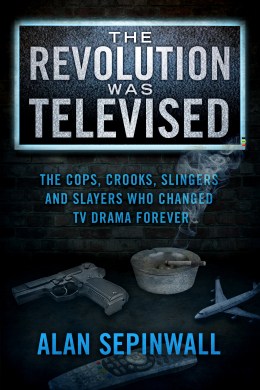

In his new book on that period in TV, The Revolution Was Televised, my fellow critic Alan Sepinwall uses a kind of hybrid episodic/serial format to tell that story itself. The book is a series of chapters—12, just enough for an HBO season—each on a different marquee drama of the recent past. And you could read it that way, dipping here and there to find out how Lost evolved from a quick brainstorm to the twistiest TV entertainment of all time or how AMC expanded the ranks of cable players with Mad Men.

But read from beginning to end, it also tells a larger, ongoing story: how changes in business, technology and culture took the collaborative medium of TV and made it one that could reflect the individual auteur visions of creators. Those shows, mostly outside the major broadcast networks, made the best TV more sophisticated, richer and more varied than it had ever been before. (Though, as Sepinwall acknowledges, not automatically more diverse—the shows he profiles are almost entirely the work of white men.)

This serial change, though, is the result of many individual triumphs, frustrations and happy accidents, and that’s where the fun of Revolution is. Staring with HBO’s Oz and ending with AMC’s Breaking Bad, he walks through the challenges of the creators, each of whom, in some way, was trying to get something on air that hadn’t really been done before. (The book is roughly chronological, though Sepinwall takes the liberty of moving Buffy the Vampire Slayer later in order.)

It’s a zippy read, data-packed without being gossipy—in line with the interests of Sepinwall’s smart TV blog, What’s Alan Watching?—and packed with detailed stories from creators, producers and executives. (One rare exception: Mad Men’s Matthew Weiner cited a busy work schedule and declined an interview.)

So we hear about one of the rare creative run-ins David Chase had with HBO in making The Sopranos, as former exec Chris Albrecht recalls recoiling at having Tony Soprano murder a mafia rat with his bare hands in the show’s fifth episode. “And David said to me,” Albrecht remembers, “‘If Tony Soprano were to find this guy and doesn’t kill him, he’s full of shit, and therefore the show’s full of shit.'” (More tantalyzingly, we learn that HBO had to decide whether to make The Sopranos at all, or a drama from My So-Called Life’s Winnie Holzman about a businesswoman–a decision that, had it gone the other way, could have dramatically changed not only the channel’s history but the development in the antihero in pop culture.)

That’s the kind of tidbit Revolution is concerned with: how the business process helped and hindered the creative process, more than who was snorting what with whom. So we read, for instance, about the season six of The Wire that David Mills suggested to creator David Simon but never came to be, which would have focused on Baltimore’s Latinos. (“Given the low ratings and the fight for Season 4, Simon didn’t feel the moment was right to go to Albrecht and say, ‘We’ve got a great idea! Now there’s gonna be a bunch of Latino actors!'”) We read a many-sided Rashomon about the end of Deadwood that doesn’t absolutely resolve who killed that Western but–no spoilers!–sheds new light on how why David Milch and HBO ended it. And we read how Lost got on air in a whirlwind development, with J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof smiling and nodding at network requests, all the while planning a baroque, bizarre mytho-drama that never would have gotten on the air in normal circumstances.

Sepinwall, as you probably already know because here you are reading a TV blog, is a sharp and prolific critic in his own right. In Revolution, though, he admirably often stands back and lets his subjects’ words speak for themselves. But then he stitches the narrative together with insights that will make you see anew just how a Friday Night Lights or Buffy season truly worked, while tossing off the kind of dead-on descriptions that make his blog a blast to read. (“You didn’t so much watch The Shield as get beat up by it for an hour before it went off to grab a few beers and find a pimp to hassle.”)

The chapters, in fact, read something like rich, extended cut versions of What’s Alan Watching? posts, right down to the trademark “footnotes” that he intersperses between paragraphs. The book is bloggy in all the right ways, while offering the kind of big-picture sweeps of TV history that episode recaps—Sepinwall’s online bread and butter—don’t always allow. (Also in the DIY blog spirit—Sepinwall began recapping NYPD Blue in online newsgroups in the ’90s, before recapping was cool—the book is self-published: You can order it in paperback as well as from Kindle, Nook and the iBooks store.)

As with an expansive drama, there are endless alleys Revolution could have pursued and didn’t. Its focus is very much on the Serious TV Canon dramas of the last decade and a half, with special emphasis on cable dramas and their network kin like Friday Night Lights. So, for instance, there’s no The West Wing or Grey’s Anatomy (on the grounds that they’re more-traditional broadcast dramas that might have aired pre-Sopranos). I’d have liked to see Sepinwall’s take on a few messier, more idiosyncratic shows like Glee or influential one-season wonders like Freaks and Geeks. (Sepinwall, I’d guess, would argue that both shows are at least half comedy.) And I wouldn’t have minded him pulling the camera back more often for a greater sense of the larger world in which these shows were made and received, as he does with the 9/11 era in the 24 chapter.

But that’s me; I’m greedy that way. Like the creators of the shows he illuminates here, Sepinwall isn’t trying to be everything to everyone. He’s made his choices to tell a specific narrative of important TV as he defines it, chasing an ambitious, adventurous, shapeshifting Spirit of the Tube from the Scooby Gang’s headquarters to Walter White’s meth lab. For any lover of TV—or a lover of a lover of TV who’d like to see them crack a book for once—it’s a perfectly timed holiday gift. Don’t think of The Revolution Was Televised as a mere book. Think of it as the ultimate DVD-set commentary.