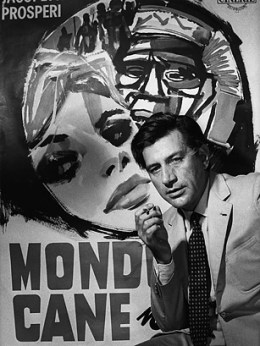

Gualtiero Jacopetti, film director of Mondo Cane, 1963

“Mondo,” being the Italian word for world, should be a neutral noun. Yet go to any modern dictionary and find a variety of definitions far from the original. “Adjective: enormous; huge; extremely unconventional or bizarre.” “Adverb: Used in reference to something very striking or remarkable of its kind.” The Urban Dictionary provocatively calls Mondo “the quintessential word of the English language.” What all contemporary linguists agree on is that it derives from the 1962 “documentary” Mondo Cane. So it’s worth recognizing the film’s writer and supervising director, Gualtiero Jacopetti, who died Aug. 17 at 91.

Born in Barga, Tuscany, in 1919, Jacopetti served in the Italian Resistance during World War II and co-founded the liberal newsweekly Cronache in 1953. He worked on newsreels, and a couple of docs about the seamier night clubs on five continents, before having his eureka-Mondo inspiration. “Let’s make an anti-documentary,” he told his colleague Franco Prosperi, who would be Jacopetti’s codirector for the next decade. The result was Mondo Cane, which means Dog World in Italian — “an ironic, mocking, even cynical title,” Jacopetti recalls in David Gregory’s exemplary 2003 doc The Godfathers of Mondo — but which was released in English-speaking countries under its original title. Hence, Mondo.

Jacopetti wasn’t the first filmmaker to marry sensation to documentary. The early shorts produced by Thomas Edison’s company opened viewers’ eyes to cockfights, cootch dancers and, in 1903, the electrocution and death of Topsy, a Coney Island elephant. Audiences loved that the movie camera could take them places they’d never been and show them things they’d never seen, and in 1922 they got their first feature-length true-life adventure. In his ethno-smash Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty filmed the working and community life of an Inuit fisherman in faithful detail — except that the Eskimo wasn’t named Nanook, and many scenes were restaged for the camera. Flaherty believed a filmmaker had to bend certain facts to tell a larger truth, and the documentary ethos would henceforth pirouette between reportage and reenactment.

Cellar-dwelling filmmakers soon added the erotic to the exotic. J.C. Cook’s 1934 Inyaah (Jungle Goddess), which intercut stock footage with a location shoot in Indonesia, purported to record the strange folkways of tribal races, where the men are fierce and the woman pretty and topless. The peculiar American mores of the time forbade nude images of whites but saw ethnographic value in shots of unclothed African or Asians; it’s one reason many boys became connoisseurs of photo spreads in the National Geographic. Exploitation movies just upped the ante: to National Pornographic — a tendency Jacopetti and his team would bring to cinematic fruition.

Jacopetti expanded that adolescent voyeurism to the whole world. “Cinema,” he said, “was the perfect medium to tell the facts of life,” and he’d tell them all. Jacopetti and his team — Prosperi, second codirector Paolo Cavara and cameramen Antonio Climati and Benito Frattari — circled the globe for lurid scenes, acting like the nerviest tabloid photographers whose only goal was to get the story. “Back then the whole world was unprepared for our shooting strategy,” Prosperi says in The Godfathers of Mondo. “Slip in, ask, never pay, never reenact.” (Well, maybe sometimes they did stage reenactments, but, hey, so did Flaherty.) Mondo Cane upended the Italian film tradition of neorealism — movies on working-class themes shot in a naturalistic style — for a kind of sociological hyperrealism.

In the process it defibrillated the staid documentary tradition: here were startling images, abrupt juxtapositions, the violent voyeurism of the new zoom lens and Jacopetti’s scathing narration. TIME’s review of the film gave a hint of the filmmakers’ dialectical scheme: “After ogling a beachful of bikinied bosoms, the camera cuts abruptly to a woman in New Guinea nonchalantly nursing a small, bristly pig, cuts again to a nearby village, where screaming hogs are being clubbed to death by natives in preparation for a barbecue.” Wrote the magazine’s unnamed critic: “If there’s a message, it’s that people are no damn good.” And yet, as Michael Weldon noted decades later in The Psychotronic Video Guide, “There’s sense and irony in everything, The film made audiences think while shocking them.”

The movie’s opening narration read: “All the scenes you will see in this film are true and are taken only from life. If often they are shocking, it is because there are many shocking things in this world. Besides, the duty of the chronicler is not to sweeten the truth but to report it objectively.” The objectively reported truths included such antic behaviors as snake-eating, bull-goring, pet necrophilia, a woman suckling a pig, livestock beheaded with a sword, a restaurant that serves canned ants, an artist who paints nudes. Paints their nude bodies blue, that is.

Jacopetti also hired the composer Riz Ortolani to write a full, Hollywoodish score, whose inappropriate but irresistible love theme “More” (“More than the greatest love the world has known”) was nominated for an Oscar and went on to be played at nearly every wedding for the next 20 years. This weird mix of horror and humor — that you could hum to — made Mondo Cane a worldwide hit. The Guardian‘s Mark Goodall fairly pegs it as “the strangest commercially successful film in the history of cinema.”

Mondo quickly became a 60s cult word, up there with Disco and Go-go, and its own film genre: the exploitation doc, or trashumentary. Russ Meyer’s Mondo Topless (a Baedeker of San Francisco strip joints) and R.L. Frost’s Mondo Bizarro and Mondo Freudo cashed in on the trend. Mondo Hollywood, Mondo Teeno, Mondo Mod — any word could be added to a title to clue audiences that they would see something bizarre and titillating. And in 1977 Saturday Night Live’s proto-misanthrope Michael O’Donoghue parodied the original film with Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video, in which the sepulchral host and his crew of “top Italian journalists” expose such oddities as an island cult that worships Hawaii Five-O star Jack Lord and a Parisian restaurant that serves rabbit poop — all scored to a “More”-like ballad (actually the surfer instrumental “Telstar” with new lyrics). Produced by Lorne Michaels, Mondo Video was intended as the pilot for a show that would fill SNL’s slots during dark weeks. NBC went “Huh?” and the film slipped into the midnight-movie repertoire.

By expanding or lowering the standard for what people would watch, Mondo Cane indirectly spawned nearly everything lurid that followed it, from the Faces of Death and Shocking Asia fakeumentaries of the early VCR age to the exhibitionism of talk-show and reality TV. In The Godfathers of Mondo, critic Jeffrey Sconce points out how the Fox network in the 1990s plundered Jacopetti’s style and tone with the Cops docu-series and such tabloid exposés as When Good Pets Go Bad and Extreme Behavior Caught on Tape. And what is the Internet but a delivery device for all things Mondo?

Jacopetti and Prosperi made a couple of sequels to the biggest hit (the 1963 Women of the World and the 1964 Mondo Cane 2), but they had grander ambitions. Their salacious 1966 doc Africa Addio 1966) depicted in unforgiving detail the birth pangs of post-colonial Africa: the Mau Mau uprising, the Zanzibar revolution, the friction of blacks and whites in Kenya. This was guerrilla filmmaking at its most intense. In Dar al-Salaam, Tanzania, the crew was arrested, perhaps to be shot, when an officer arrived shouting, “Stop — they’re not whites [i.e., English], they’re Italians.” (Prosperi recalls that as “a phrase that saved our life.”) When Jacopetti was taken off to be interrogated or worse in the Congo city of Stanleyville, he turned to his cameraman and said, “Smile, smile,” so they would show their captors no fear. “Gualtiero was a man of extraordinary charisma,” Prosperi says. The man could bluff his way out of almost anything.

But not the accusation by critics that Africa Addio suggested that the civilized whites had left the continent to its savage natives. Roger Ebert, in one his first reviews as critic of the Chicago Sun-Times, “of executions, decomposed bodies, burning flesh, suffering and death…that they are staged for our amusement, cloaked in the respectability of an ‘impartial’ documentary, and in the end that is the most disgusting thing about this wretched film.” (Ebert was reviewing the American version, significantly shorter than the 2hr.19min. original, and with a different narration; but he probably wouldn’t have liked the directors’ cut either.) In The Godfathers of Mondo, Prosperi sighs that “The public was not ready for this kind of truth”; and Jacopetti argues that Africa Addio “was not a justification of colonialism, but a condemnation for leaving the continent in a miserable condition.” Unfortunately for Africa, much of it is still in that condition.

After a newspaper column written by a friend of the filmmakers who had visited them on location and charged them with staging the execution of one prisoner, a murder charge, Jacopetti was tried for murder in an Italian court. The film’s footage was seized; a police sign on the editing-room door reads “Confiscated due to massacre.” Jacopetti and Prosperi produced documents showing that they had come on the scene just before the shooting, and Jacopetti was acquitted. Someone must have liked Africa Addio: it won the David di Donatello award (the Italian Oscars) for Best Production, tied with Pietro Germi’s comedy Signore & Signori and John Huston’s The Bible…in the Beginning. The Minister of Education was supposed to present the prize to Jacopetti and Prosperi, but he refused.

Determined to prove their racial liberalism, the filmmakers thought they had another great idea: as Prosperi said, “Why don’t we do Mandingo as a documentary?” Kyle Onstott’s 1957 novel about sex, violence and slavery on an Alabama plantation would become a Hollywood movie in 1975, but Jacopetti and Prosperi got there first and went further. Addio zio Tom, shown in a shortened American cut as Goodbye Uncle Tom, borrowed the time-traveling doc style of the CBS show You Are There, but in scope and ambition it was one of the boldest of all mockumentaries, and one of the earliest (after Woody Allen’s Take the Money and Run).

In the first scene, the Italian filmmakers helicopter low over plantation fields, the blades stirring dirt into the faces of the slaves — suggesting that the film will both sympathize with the slaves and somehow tarnish them. The camera then enters the master house, where fancy-dress white people sit at dinner. “These gentlemen are my guests,” the matronly hostess tells the others at the table, “so they can learn who really are the slaves and masters here.” When a woman supposed to be Harriet Beecher Stowe argues against slavery while a “professor” states that “God is white, and as long as God is white we shall prevail of all other races,” an elderly black servant stares glumly, three black boys fan the guests and two others are fed chicken bones under the table.

The movie was shot in Haiti, where Jacopetti and Prosperi were guests of Papa Doc Duvalier; they were given diplomatic cars, the run of the island, as many extras as they wanted and dinner every Friday with the dictator. Addio zio Tom says that slavery was bad, but that watching torture — the degradation of humans by humans of a lighter hue — has a therapeutic value to the viewer. Scene after scene depicts the selling of naked black men and pregnant women by the ruling class. Ogling is encouraged in a film that’s still supremely difficult to watch; the camera considers the whites with a sneer and the blacks with a leer. Frattari, the Mondo Cane cinematographer, worked briefly on the shoot and later said, “The film was born bad and was going to end up worse.”

Banned or severely cut in several countries, Goodbye Uncle Tom in all its excess provoked Ebert to a level of disgust that made his Africa Addio review seem mixed. “The vile little crud-squad of Jacopetti and Prosperi” has produced a “vomit-bag of racism and perversion-mongering… the most disgusting, contemptuous insult to decency ever to masquerade as a documentary.” He called the employment of Haiti’s poor in the film “cruel exploitation. If it is tragic that the barbarism of slavery existed in this country, is it not also tragic — and enraging — that for a few dollars the producers of this film were able to reproduce and reenact that barbarism?” If the film is recalled fondly today, it is for Ortolani’s rapturous score; the movie’s theme song, “Oh My Love,” appears on the soundtrack of the new Ryan Gosling film Drive.

Uncle Tom was a flop and an embarrassment, and the last of the Jacopetti-Prosperi collaborations. A feud between the two had simmered for years, but hit films and a shared view of the medium’s subversive possibilities kept them together. After they split, neither reached the heights of their early successes, and Jacopetti returned to print journalism. But a movie career doesn’t need a happy or tragic ending to give it significance. Once upon a time, Jacopetti created a movie that altered, arguably liberated and certainly coarsened popular culture. He made the world Mondo.